Key points

- Strong resistance to phosphine in stored grain insects has both increased and spread over the past decade, with more detections in eastern Australia than Western Australia

- Misuse of phosphine, particularly in unsealed storages, appears to be the main reason for the development of strong resistance

Australian growers have relied heavily on phosphine fumigation to disinfest stored grain and meet market expectations for high-quality grain with nil tolerance to insects. However, reliance on one chemical over a long period of time has led to resistance.

Surveying resistance

Since 1996, GRDC’s ‘National Phosphine Resistance Monitoring’ project has monitored resistance to inform research and develop strategies to help growers protect the reliability of phosphine fumigants.

Rusty grain beetle, one of the flat grain beetles, was not the first insect pest in Australia to develop strong resistance to phosphine. But when a resistant population was first detected in NSW in 2007, it had the strongest level of resistance to phosphine anywhere in the world and could not be controlled with the label rate.

Practices such as use in unsealed storage, storing grain for longer durations and incomplete cleaning of storages all increase the risk of insect infestations requiring control. Multiple poor fumigations of the insect populations can result in resistance.

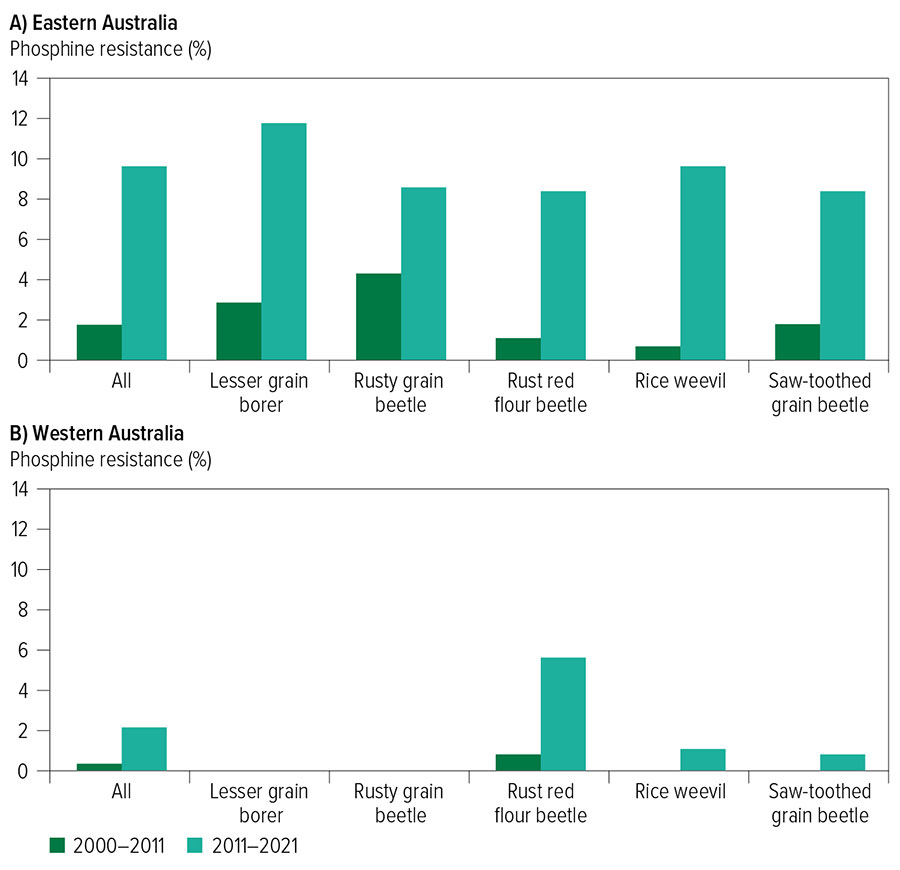

Resistance is more common in eastern Australia, where the proportion of strong resistance has increased in the five major stored grain insect pests over the past 10 years (Figure 1A). When all species are combined, it has increased more than fivefold – from 1.8 per cent (mid-2000 to mid-2011) to 9.6 per cent (mid-2011 to mid-2021). The lesser grain borer had the highest proportion of strong resistance, at 11.7 per cent.

In Western Australia, the percentage of populations with strong resistance has also increased by five times, from 0.4 per cent (mid-2000 to mid-2011) to 2.2 per cent (mid-2011 to mid-2021) (Figure 1B).

Prior to 2011, strong resistance to phosphine on farms in WA was only detected in the rust red flour beetle. Since then, strong resistance has also been detected in the rice weevil and saw-toothed grain beetle, although these populations were quickly contained.

Figure 1: The proportion of stored grain insect populations with strong resistance to phosphine collected from farms mid-2000 to mid-2011 and mid-2011 to mid-2021 in A) eastern Australia and B) Western Australia.

Source: Dr Jo Holloway.

Preventing spread

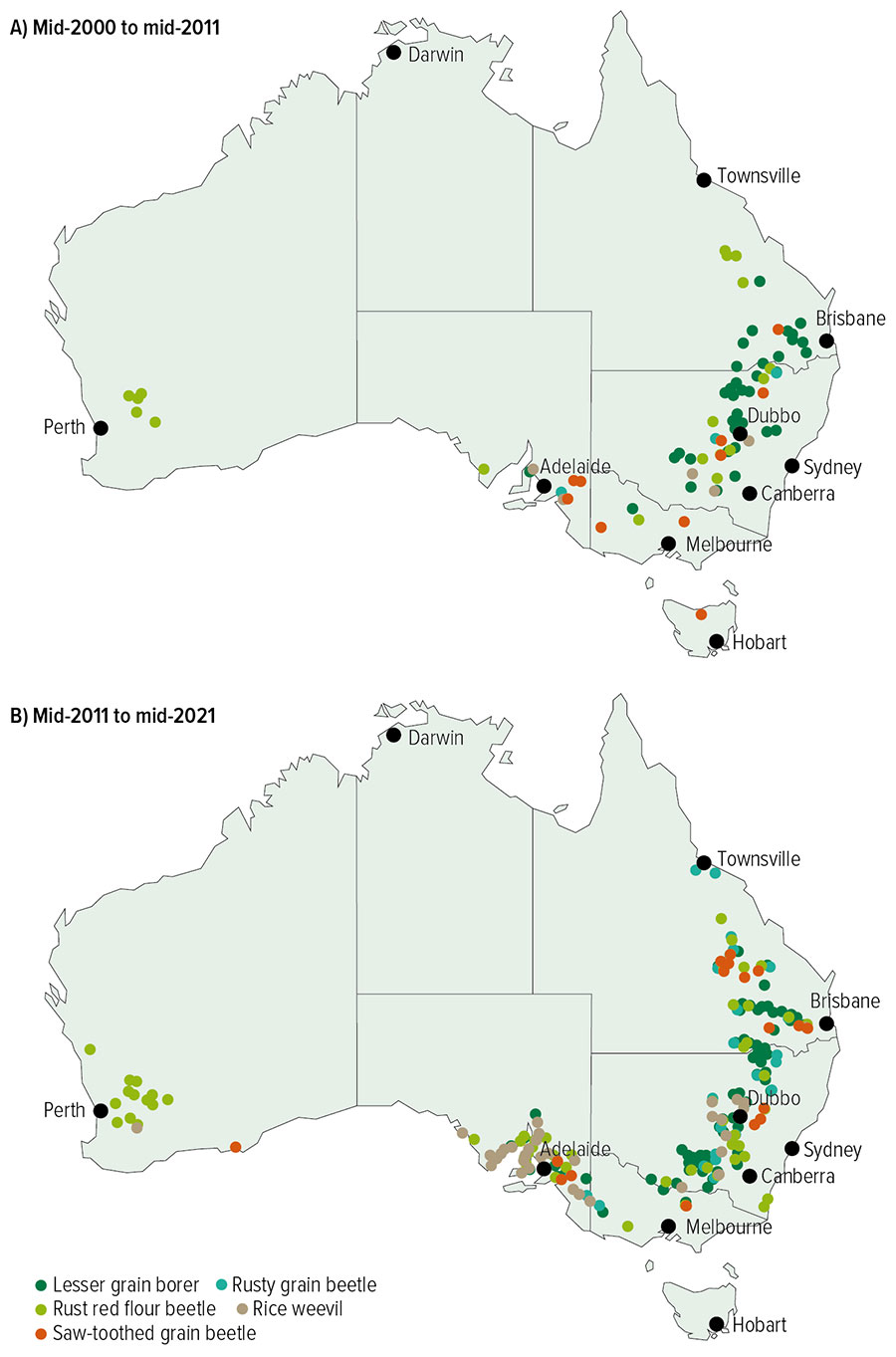

Strong resistance to phosphine can develop and spread quickly. Resistance in stored grain insects has now spread throughout the grain growing regions in all states, with the greatest increases observed in South Australia (Figure 2).

For example, after its first detection in 2007, rusty grain beetle had spread to four farms by 2011 – in NSW and South Australia. However, by 2021 it had spread to Queensland and Victoria, with a total of 53 detections across eastern Australia.

Figure 2: Locations of stored grain insect populations collected from farms A) mid-2000 to mid-2011 and B) mid-2011 to mid-2021 with strong resistance to phosphine.

Source: Dr Jo Holloway.

While the expansion of surveys into new regions, such as Townsville, can explain some of the increased spread, the main culprit is the misuse of phosphine – particularly in unsealed storages.

Phosphine requires time to be effective against all life stages, particularly eggs, and should only be used for grain fumigation in gas-tight storages.

Phosphine is a particularly mobile gas and concentrations fall below recommended levels when used in non-gas-tight structures. Practices such as use in unsealed storage, storing grain for longer durations and incomplete cleaning of storages all increase the risk of insect infestations requiring control. Multiple poor fumigations of the insect populations can result in resistance.

Storage seals deteriorate over time, leading to gas leakage. Growers need to maintain sealed storages and pressure test prior to fumigation. Monitor grain for insects, particularly after a fumigation and, if found, send them to the nearest laboratory for resistance testing and advice.

The ‘National Phosphine Resistance Monitoring’ project is led by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, in collaboration with the NSW Department of Primary Industries and the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

More information: Dr Jo Holloway, 0410 410 736, joanne.holloway@dpi.nsw.gov.au