In our GroundCover rust article earlier last year (March–April 2021 edition), we reported incursions of two exotic stripe rust pathotypes (races or strains) into eastern Australia. These included, in 2017, the ‘239 pathotype’, likely from Europe, and, in 2018, the ‘198 pathotype’, likely from either Europe or South America, which brought the total number of wheat stripe rust incursions into Australia to four.

Two previous incursions of exotic stripe rust isolates occurred in 1979 and 2002. Both resulted in significant costs to the wheat industry. For example, between $40 and $90 million was spent annually on fungicides in 2003, 2004 and 2005 as a direct consequence of the 2002 incursion.

The more recent introductions of two very different stripe rust isolates in successive years is unprecedented, creating challenges even greater than those we faced in dealing with the two previous incursions.

The impact of exotic cereal rust incursions was on full display in eastern Australia during the 2021 season, especially across much of the northern grain growing region where stripe rust was very common and, in some cases, caused significant crop infection.

Conditions in the 2021 cropping season were generally milder, leading to slower crop development, more pathogen cycling and delayed onset of adult plant disease resistance that left some crops unprotected between usual management growth stages.

This followed a very early epidemic onset (first detection was on 25 May, but the 40-year average for its first detection is 13 July). The early epidemic onset is thought to have resulted from significant green bridge survival over the 2020-21 summer break.

Confusion for growers

Despite the favourable conditions for stripe rust development in 2021, the biggest and most confusing aspect for some wheat growers was changes in the responses of some varieties to stripe rust compared with the 2020 season, with some varieties being sprayed with fungicide for the first time.

These varietal response changes can be explained by the disease resistance the varieties carry and a change in the frequencies of the two exotic pathotypes that occured in 2021.

Of the nearly 300 identifications we made of stripe rust in 2021, 92 per cent were either the 198 or 239 pathotypes.

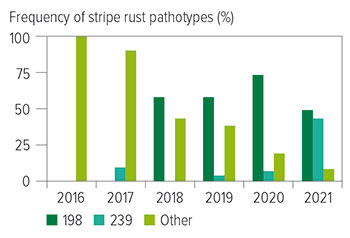

While these two pathotypes were also the most common in 2020, accounting for 80 per cent of the stripe rust isolates identified, the big change in 2021, compared with 2020, was the increase in the incidence of pathotype 239 – up from just seven per cent of all identifications in 2020 to 43 per cent in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Frequency (percentage) of stripe rust pathotypes, showing the incidence of the 198 pathotype and 239 pathotype compared with other pathotypes from 2017–2021. Pathotype 239 was first detected in 2017 and pathotype 198 was first detected in 2018. The large increase in the frequency of pathotype 239 in 2021 meant that some wheat cultivars were more susceptible to stripe rust in that year. Source: University of Sydney

As some varieties are resistant to 198 pathotype, but susceptible to 239 pathotype, the increased frequency of the 239 pathotype in 2021 meant that while such varieties displayed resistance in 2020, they were more susceptible in 2021.

Examples of these varieties were Catapult, Coolah, LRPB Flanker, RockStar and Vixen, which carry resistance genes Yr25, Yr33 or another uncharacterised resistance gene, all of which protect against pathotype 198, but not pathotype 239.

Adding to the confusion was that some varieties are more vulnerable to the 198 pathotype than they are to 239 pathotype; for example, DS Bennett, LPB Trojan and Borlaug 100 and, to a lesser extent, Devil, Illabo, DS Darwin, Emu Rock and Hatchet CL Plus.

Pathotype 198 is also a greater threat to several durum wheat varieties; for example, DBA Artemis, DBA Bindaroi, DBA Lillaroi, DBA Spes, DBA Vittaroi and EGA Bellaroi, as well as the triticale varieties Astute, Berkshire, Bison and Joey.

Obtaining accurate data on the rust responses of wheat cultivars to new rust pathotypes often takes several years of field assessments, combined with greenhouse testing to establish a genetic basis for any differences found.

Our work at the Plant Breeding Institute, and with our regional collaborators, has generated a much-improved understanding of what is being seen, not only in commercial crops but also in the breeding pipelines that will deliver new, improved wheat varieties to growers in the years to come.

Updated, refined varietal stripe rust responses will be provided in early 2022 based on results from the National Variety Trials 2021 cycle.

The experiences of 2021 yet again underscore the importance of growing rust-resistant cereal varieties whenever possible and avoiding highly susceptible ‘rust suckers’.

Unlike many cereal pathogens that are either soil-borne and do not spread readily, or some foliar pathogens that have limited aerial dispersal, the rusts are ‘social’ diseases that spread rapidly on wind currents across thousands of kilometres.

Information on the cereal rusts can be found in the University of Sydney’s periodic Cereal Rust Reports and a regularly updated map of the distribution of rust pathotypes can be found on its website.

Growers are urged to forward freshly collected rust samples (in paper only) to the Australian Cereal Rust Survey, the University of Sydney, Australian Rust Survey, Reply Paid 88076, Narellan, NSW 2567.

More information: Robert Park, 02 9351 8806, robert.park@sydney.edu.au