Key points

- Keep paddocks free of weeds, especially volunteer cereals, during summer and autumn

- Know the current disease resistance ratings of cereal varieties because they can change

- Ensure you get a correct disease diagnosis prior to implementing control measures

- Aim to protect the top three leaves with correctly timed fungicides

- Alternate the use of fungicides with different modes of action and even rotate within triazole (Group 3) actives to delay the onset of pathogen resistance

Plant pathologists are asking growers to pay careful attention to pre-sowing weed control to reduce the risk of disease and virus carryover from last year’s crops into this year’s crops.

Brad Baxter, a NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) plant pathology research officer based at the Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute, says complete control of cereal volunteers and other grass weeds destroys this green bridge.

His research supported by GRDC co-investment with NSW DPI – involves screening commercially released and close-to-release cereal and pulse varieties at NSW DPI’s disease nursery in Wagga Wagga.

Data collected from the Wagga Wagga nursery is combined with data sourced from similar NSW DPI nurseries at Tamworth and Grafton. This data is then combined with national data sets to assign resistance ratings for commercial varieties.

Mr Baxter says disease nursery data, evidence from random paddock surveys across more than 275 NSW locations, and more than 700 enquiries from agronomists and growers put stripe rust at the top of the list of cereal diseases in 2021.

“All rusts are biotrophs, which means they need to host on a living plant to survive between crops,” he says.

“Destroying volunteer cereal and weed hosts, and hence the green bridge, delays the onset of rust epidemics, particularly if growers across large district-wide areas adopt this management tactic.

“Although leaving volunteer cereals and weed hosts uncontrolled for livestock to graze is tempting, from a crop protection perspective, removing livestock from paddocks well before sowing and keeping your paddocks free of these hosts is critical to reducing early disease pressure and giving this year’s crop the best chance of reaching its potential.”

Go host-free

Mr Baxter says a useful tactic, particularly in wet and cool summer and autumns – as is forecast – is to keep paddocks host-free for at least one month before sowing long-season varieties.

“If growers from across whole districts keep paddocks host-free for at least one month, the rust pathogen life cycle breaks down and the carryover of inoculum on to early sown cereal crops will be significantly reduced,” he says.

“We suggest February as the optimum month to aim to have paddocks as host-free as possible ahead of when winter wheat varieties start being sown in most high-rainfall areas.”

NSW DPI plant pathologist Dr Steven Simpfendorfer agrees, adding that the flush of volunteers that emerged after December 2020 and January 2021 rains were viewed by some northern NSW growers as a valuable source of much-needed feed.

“With plenty of rain in summer and autumn 2020-21, some growers even attempted to hang on to volunteers and take them through to harvest, which led to an elevated stripe rust risk for 2021 crops,” Dr Simpfendorfer says.

“This, coupled with above-average rainfall, widespread sowing of long-season wheat varieties and reduced use of in-furrow fungicides, brought forward the onset of stripe rust.”

By way of example, Mr Baxter points to grass weeds and oat volunteers hosting oat crown rust and stem rust during February 2021, which is well outside the window of when these diseases are normally found.

“These diseases are usually found in the second half of the cropping year, so this indicates the rust cycle – and the green bridge – was not broken from 2020,” he says.

“Stripe rust infection of wheat heads, which gains entry to the glumes when wheat crops flower, was a particular concern to those who had not seen it before.”

Stripe rust infection of wheat heads. The pathogen enters plants through the glumes when wheat crops flower. Photo: Nicole Baxter

While stripe rust was the main disease issue in cereal crops last year, Mr Baxter says destroying the green bridge, crop rotation and reducing the cereal stubble load just before planting are also valuable tactics to protect cereal crops against other leaf and root diseases.

“Such diseases include Septoria tritici blotch and yellow spot in wheat or spot form net blotch, scald and net form net blotch in barley,” he says.

“Soil-borne diseases such as Rhizoctonia root rot, take-all common root rot and Fusarium crown rot also build up more in rotations with a higher frequency of cereal crops and stubble retention.”

Yellow leaf spot infection is often seen early in wheat/wheat rotations, Dr Simpfendorfer says, as primary infection occurs from inoculum carried over on wheat stubble.

“However, continued rainfall during the season is required for secondary infection from these initial leaf lesions to see the disease spread through the canopy.

“A lot of 2021 wheat crops were treated with in-crop fungicide, often primarily for stripe rust management, which would have also slowed the progression of yellow spot,” he says.

“We saw a fair bit of Septoria tritici blotch in 2021, south from Narromine. The time from infection to display of symptoms, or latent period, is up to 28 days; what disease levels you see in the crop is not necessarily what you will end up with.”

Fusarium crown rot

Under the GRDC-NSW DPI Grains Agronomy and Pathology Partnership, a random paddock survey of key crop pathogens is carried out each year across more than 275 NSW wheat and barley paddocks.

In areas around Balranald and Deniliquin in southern NSW, where seasonal conditions were drier, Mr Baxter says wheat plants were identified as hosting Fusarium crown rot. Typically, this pathogen causes the largest or second largest losses in wheat production in most regions.

“In several paddocks, the pathogen had built up in the base of the plant to such high levels that it had actually killed whole tillers and we found examples of white heads that were either empty or had pinched and shrivelled grain,” he says.

“Growers in higher-rainfall districts may not have seen the characteristic white heads and stem browning due to soft spring conditions.

“In heavy cereal rotations, the Fusarium crown rot inoculum was likely present in the crop, maintaining or increasing inoculum loads in the paddock and potentially reducing yields.”

Mr Baxter says Fusarium crown rot trials at Wagga Wagga during 2015 showed that even in the absence of a significant yield loss between inoculated plots and non-inoculated plots, there was a significant difference in grain quality, which carries an economic cost.

In other trials overseen by Dr Simpfendorfer at Breeza, near Tamworth, under a fully irrigated farming system, trials showed about 10 per cent yield loss in wheat inoculated with Fusarium crown rot.

“This research demonstrates that even in a wet year, those who have planted cereals after cereals will be driving inoculum levels upward and maintaining risk of this yield-robbing pathogen in their paddocks,” Mr Baxter says.

Dr Simpfendorfer adds that if a cereal crop is to be planted into cereal stubble, growers should have soils tested for inoculum levels using the PREDICTA® B test. The test quantifies the level of soil-borne pathogens in the soil and allows paddocks with lower levels to be selected to minimise the disease risk.

“Current seed treatments registered for the suppression of Fusarium crown rot are inconsistent in reducing the extent of yield loss from this disease,” he says.

Dr Steven Simpfendorfer. Photo: Brad Collis

“Victrato® appears to have more consistent and stronger activity on limiting yield loss from Fusarium crown rot but will not be available commercially until at least 2024.

“However, under high infection levels, as created with artificial inoculation in our experiments, significant yield loss may still occur, particularly in drier seasons.

“Consequently, fungicide seed treatments, including Victrato®, should not be considered standalone control options for Fusarium crown rot.

“Rather, they should be used as an additional tool within existing integrated disease management strategies for this disease.”

Dr Simpfendorfer says integrated disease management tools to reduce the risk of Fusarium crown rot include timely sowing, growing a double break non-host crop such as a pulse followed by a canola crop, inter-row sowing and matching nitrogen supply to available soil moisture to avoid exacerbating moisture stress during grain filling.

“If a cereal must be grown in a high Fusarium crown rot risk situation due to operational or agronomic constraints, consider sowing barley instead of wheat,” he says.

“Barley’s phenology will allow for earlier maturity, potentially reducing heat and moisture stress during grain fill.

“However, this is a single-season ‘Band-Aid’ solution, as barley is also a very good host of Fusarium crown rot and will not reduce the inoculum load for subsequent cereal crops in the rotation.”

Resistance ratings

Another way to reduce potential yield loss to diseases, Dr Simpfendorfer says, is to annually check the disease resistance rating of varieties earmarked for sowing.

“Disease resistance genes within varieties do not change; rather, various pathogens can mutate or exotic pathotypes are accidentally introduced from overseas and overcome single or multiple resistance genes found in a variety, which can lower a variety’s resistance rating,” he says.

“How far the rating drops depends on what other resistance genes are also sitting in the background within individual varieties.”

In terms of stripe rust, he says the challenge is knowing which pathotypes are present throughout the growing season and their geographical distribution.

“Given the widespread distribution of the 239 and 198 stripe rust pathotypes in 2021, greater emphasis should be placed on varietal resistance to these pathotypes in 2022,” he says.

“However, lower frequency pathotypes could still cause more localised issues in some varieties in 2022, so should not be dismissed.

“The disease resistance ratings on GRDC’s NVT site are usually updated by March each year to reflect the expected reactions to known rust pathotypes.

“A check of the most up-to-date resistance ratings may also help a risk-adverse person decide whether to plant more of a variety – for example – with an ‘MR’ (moderately resistant) rating for stipe rust, and less of another variety that may have a ‘S’ (susceptible) or ‘VS’ (very susceptible) rating.”

A more in-depth look at the issues surrounding stripe rust can be found by visiting GRDC’s Paddock Practices: Stripe Rust. Live results of strip rust strains can be found on the University of Sydney Rust Reports web page.

Correct diagnosis

During the season, Dr Simpfendorfer and Mr Baxter encourage growers to seek help to secure a correct disease diagnosis.

“Underlying issues with nutrients, herbicides and other stresses can cause some yellowing or discolouration of leaves,” Dr Simpfendorfer says.

“Physiological spotting not related to disease occurs in barley every year and is easily confused with spot form net blotch; however, this disease has clear patterns of distribution within plant canopies and even on individual leaves.

“There have also been reports of growers wrongly attributing yield losses to stripe rust head infection when symptoms and paddock distribution were actually more consistent with frost damage.

“Feel free to send either Brad or myself a text message with a few high-quality photos if you see anything of concern that you want help identifying quickly, and we can then request submission of samples if not obvious.”

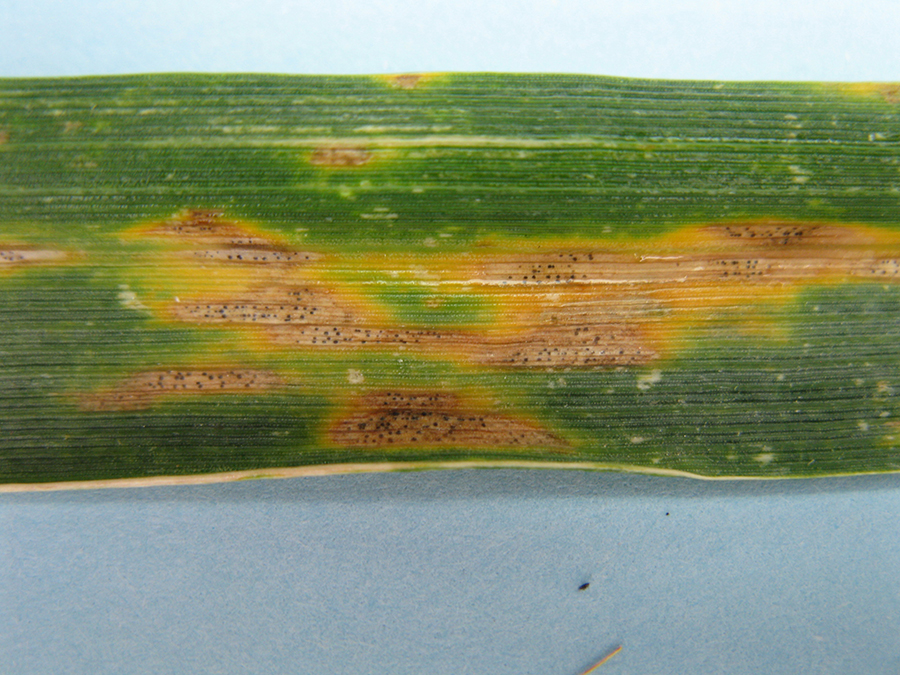

In Mr Baxter’s experience, yellow leaf spot and Septoria tritici blotch in wheat are often confused.

“Septoria tritici blotch appears more angular and has pycnidia, which appear as small black dots within the lesion,” he says.

Septoria tritici blotch. Photo: Grant Holloway

“Yellow leaf spot lesions are more lens-shaped, appear tan in colour and have a yellow chlorotic margin. There are no pycnidia present in the lesion and this is the definitive diagnostic characteristic between the two diseases.”

Last year, Mr Baxter received samples of wheat plants for disease identification from the high-rainfall areas of Illabo, Cootamundra and Harden in southern NSW.

What was initially suspected to be a fungal leaf disease, he says, turned out to be crop damage caused by the wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV).

“WSMV can cause yield loss through head sterility, pinched grain or even plant death, he says. “When infection appears later in the growing season, the impact on the crop is less severe.”

Reports of crop damage from WSMV extended from southern NSW to as far north as Cumnock in central NSW.

Mr Baxter says management comes back to complete control of volunteers and fenceline weeds to reduce the survival of wheat curl mites, which are the vector that transmits WSMV to cereal crops through their feeding process.

“These microscopic vectors infected with WSMV spread from volunteers, weeds or nearby pasture paddocks via the wind to early sown winter wheat crops and transmit the virus directly to the newly emerging plants,” he says.

“To further minimise the risk of WSMV, avoid early sown cereals near pasture paddocks, although in mixed-farming situations this may not be possible.

“WSMV are nearly impossible to target with an insecticide spray and hence miticides are not recommended as a management tool.

“This is because wheat curl mite feeding causes leaves to curl tightly and these very small vectors are protected within the curled leaves.”

Protect the leaves

Another advantage of checking the latest disease resistance ratings for cereal varieties earmarked for planting, Dr Simpfendorfer says, is that it enables proactive management plans to be put in place to protect the top three leaves of susceptible crops against disease.

“Not all varieties will need extra protection from in-crop fungicide application if they have an adequate level of resistance to the disease of interest,” he says.

“For example, generally, wheat varieties rated ‘MR’ or better for stripe rust may not require fungicide management, even though they may still show some infections at the seedling stage.

“The only caveat here is that we have seen some varieties, such as Suntop and LRPB Lancer, take a bit more stripe rust when under high levels of background nitrogen nutrition, which realistically only drops their rating by one category.”

Pictured at the disease nursery at the Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute is a plot showing a wheat cultivar susceptible to rust on the left, compared to a resistant wheat cultivar on the right. Photo: Nicole Baxter

Mr Baxter agrees, adding that rust-susceptible varieties need to be protected with fungicide to keep the top three leaves green for as long as possible. This is because these leaves intercept the most sunlight, thereby driving grain fill and yield.

“An example of early fungicide intervention for a rust-susceptible variety might be to sow seed with starter fertiliser that has been treated with flutriafol and then implement a preventive fungicide spray treatment at growth stage 31 to 32,” he says.

“This type of strategy offers a basic level of protection for those running rain-fed farming systems that choose to grow a rust-susceptible variety.

“In a mixed-farming situation where early season wheat has been sown as a dual-purpose crop, grazing can help reduce biomass and reduce the amount of stripe rust in the canopy.

“However, be mindful of grazing the withholding period if flutriafol-treated fertiliser has been used at sowing.

“An additional fungicide treatment at growth stage 39 provides further protection until full head emergence, when adult plant resistance (APR) to stripe rust is usually expressed in ‘MS’ rated commercial wheat varieties.

“APR expression is related to both temperature and growth stage, with cool weather slowing crop development, and delaying when APR expresses, year to year.

“Crops grown under intensive irrigated farming systems may need additional protection, due to high moisture availability, humid in-crop conditions and longer green leaf retention, which are all conducive to extended stripe rust development.”

Fungicide care

When it comes to prolonging the effective use of fungicides, Dr Simpfendorfer says due care is necessary.

“When aiming to control one pathogen like stripe rust, growers should be aware that other co-infecting fungal pathogens such as wheat powdery mildew are also exposed to the fungicide application,” he says.

“Wheat powdery mildew has a lot higher probability of developing reduced sensitivity to fungicide active ingredients because of diversity in its genetic population.

“When you use a fungicide with the same mode of action (MOA) repeatedly within a season, you select for isolates within the population that are more resistant to that MOA or active ingredient, even off-target ones.

“These individuals then survive to reproduce and, over time, continued selection for the same MOA or active ingredient builds these individuals to a level where they dominate the field population and fungicides just don’t work as effectively, or at all.

“In 2020, a high frequency of genes related to reduced triazole sensitivity were identified across NSW and northern Victoria. These wheat powdery mildew populations also had some level of resistance to strobilurins. If we’re not careful, reduced sensitivity can happen with other active ingredients.”

A cautious and integrated approach to disease management is important when it comes to fungicide use, he says.

“Where possible, select varieties with higher levels of genetic resistance, for example, which reduces reliance on fungicides.

“Use crop rotation to break the cycle of other foliar, soil or stubble-borne cereal diseases and reduce the impact on crop yield.

“Always remember that fungicides work best as protectives, not curatives, to keep the top three leaves green and, importantly, aim to never use a fungicide with the same active ingredient twice in a row.”

More information: Brad Baxter,

Read: Australian Fungicide Resistance Network; Australian Cereal Rust Survey Interactive Map