Key points

- An expert in cereal disease management says to choose wheat varieties with in-built stripe rust resistance

- Plan to apply fungicide to varieties at the appropriate growth stages based on their level of genetic resistance. Do this before disease symptoms appear to protect the top three leaves from stripe rust infection

- Know the nitrogen status of each paddock because a high soil nitrogen bank will delay the onset of adult plant resistance against stripe rust

Random surveys of wheat crops in parts of the northern grains region reinforce the value of selecting wheat varieties with in-built genetic resistance to stripe rust.

NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) senior research scientist Dr Steven Simpfendorfer highlighted the survey results from north of Dubbo to southern Queensland at the Crop Protection Forum 2024*.

“For stripe rust infection, conditions must occur to facilitate five to six hours of leaf wetness, indicating that wetter seasons lead to increased infection levels,” Dr Simpfendorfer said. “Season 2021 was wet, 2022 was excessively wet, and 2023 was appreciably drier. Another factor is the temperature during spring and how long crops are exposed to temperatures between 12°C and 20°C where stripe rust cycles fastest.”

Survey results

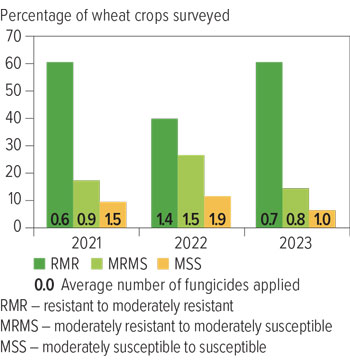

Figure 1: Fungicide applications from central NSW to southern Queensland according to season.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC

Dr Simpfendorfer noted that in 2021, nearly 31 per cent of randomly surveyed crops did not receive an in-crop foliar fungicide application (Figure 1).

“In 2022, a season more favourable for stripe rust infection, only 3.6 per cent of crops did not receive an in-crop foliar fungicide application. In 2023, 24 per cent of crops were left unprotected.”

Dr Simpfendorfer said the results confirmed growers had applied foliar fungicides according to seasonal conditions and disease risk.

“Concerningly, of the fungicide products used, there was a heavy reliance on two older triazole (DMI) active ingredients, tebuconazole (for example, Folicur®) and propiconazole (for instance, Tilt®), to manage stripe rust in each season (Figure 2). “This region is slowly progressing towards fungicide resistance, but at a reduced rate than if multiple applications of the same product were applied within an individual season.”

Data reflected the general practice of growers north of Dubbo to avoid using multiple fungicides on their wheat crops. This is related to the heavy clay soils that dominate the region. These soils potentially pose trafficability issues for ground rig spraying in wetter seasons, which are more conducive to leaf diseases.

Figure 2: Older Group 3 demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides (triazoles) dominate from central NSW to southern Queensland.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC In such seasons, logistical difficulties can also occur when chickpea crops represent a high proportion of the rotation across this region and require fungicide management of Ascochyta blight.

In 2021, 61 per cent of wheat crops surveyed across this region were rated resistant to moderately resistant (RMR) to stripe rust, while 17 per cent were moderately resistant to moderately susceptible (MRMS) and only nine per cent were moderately susceptible to susceptible (MSS) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Wheat varietal stripe rust resistance and in-crop fungicide applications across seasons from central NSW to southern Queensland.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC

In 2022, the number of RMR varieties had dropped to 40 per cent, with growers exploring increased areas of newer, higher-yielding varieties. These, unfortunately, have reduced levels of genetic resistance to stripe rust. However, following issues associated with managing stripe rust in more susceptible varieties in a high infection season, the proportion of RMR varieties planted surged back to 61 per cent in 2023 (Figure 3).

Fungicide application

Another observation was the average number of foliar fungicide applications to varieties with different stripe rust resistance ratings across seasons.

In 2021, Dr Simpfendorfer said that growers, on average, applied less than one (0.6) foliar fungicide spray to RMR varieties, 0.9 to MRMS varieties and 1.5 to MSS varieties (Figure 3).

In 2022, this increased to 1.4 applications in RMR varieties because the season was more conducive to stripe rust infection, especially at early seedling stages, and under drier conditions in 2023 it dropped back to 0.7.

He said the average number of fungicide applications applied by growers in MSS varieties also rose during 2022 to 1.9. These varieties needed more protection against disease in a high-pressure season.

“We took random plant samples from each paddock during grain fill and rated them visually for infection.

“The three top leaves, which contribute most to yield in wheat crops, were also analysed using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to determine the DNA levels of a range of fungal pathogens, including stripe rust.”

He said the study allowed regional mapping where stripe rust infections were detected and most severe in the top three leaves, highlighting the role of seasonal conditions in epidemic development.

However, individual crop data could also be linked to integrated disease management strategies to determine if this influenced stripe rust severity.

“We did not observe any RMR varieties treated with three fungicides in any season, nor MSS varieties grown without fungicide, indicating that growers made the right management decisions.”

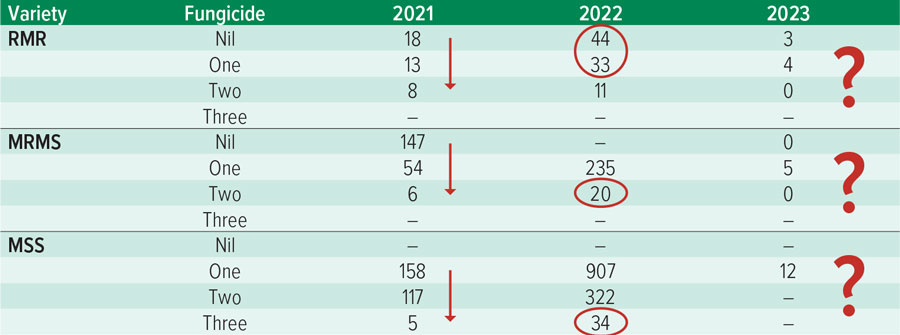

Dr Simpfendorfer said the data showed the power of growing an RMR-rated variety for protection against stripe rust (Figure 4), with lower infection levels noted across seasons and numbers of foliar fungicide application.

He said that in the wetter seasons of 2021 and 2022, the stripe rust pathogen load in MSS varieties was much higher than in MRMS varieties, with fungicide applications reducing infection levels.

“If you grow an RMR variety, the stripe rust pathogen load is significantly lower again, and the need for foliar fungicide applications is questionable.

“In 2022, an MSS variety required three foliar fungicide applications and an MRMS variety needed two, while RMR varieties required one or none to maintain a similarly low pathogen load in the top three leaves.”

However, the much drier 2023 spring, in hindsight, throws doubt on the application of foliar fungicides to RMR and MRMS varieties with the conditions being non-conducive to stripe rust development.

Figure 4: Fungicide application and stripe rust level.1

Notes: 1 Stripe rust infection was confirmed using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of the top three leaves (kDNA copies per gram). Where a dash (–) is shown, no wheat crop within the random survey occurred in this category. For example, no samples taken for RMR varieties had received three fungicide applications in the years surveyed. The question marks (?) indicate that in-crop fungicide applications appeared questionable, especially in RMR and MRMS varieties, because dry conditions during spring 2024 across the survey region were non-conducive to stripe rust development.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC

Adult plant resistance

Dr Simpfendorfer outlined how wheat varieties withstood stripe rust without fungicide due mainly to their level of adult plant resistance, which is related to a mechanism of programmed cell death.

“Stripe rust needs living wheat cells to survive, but adult plant resistance destroys the cells infected by the pathogen and those surrounding these infected plant cells. This eliminates the infection because the pathogen is deprived of a living host,” he said.

“But adult plant resistance activates at different times related to genetic resistance rating. Therefore, if your crop has experienced a significant infection before adult plant resistance is expressed, the green leaf area will be stripped from the crop canopy to kill this infection, which is not ideal for producing high grain yields.”

If adult plant resistance is expressed before infection, he said light flecking in the leaves was likely the only symptom under high disease pressure (Figure 5). “Understanding the genetic resistance of your wheat varieties is crucial so you can time your foliar fungicide application to overlap protection of the crop until adult plant resistance kicks in.”

Figure 5: Stripe rust infection in leaves without and with adult plant resistance.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC

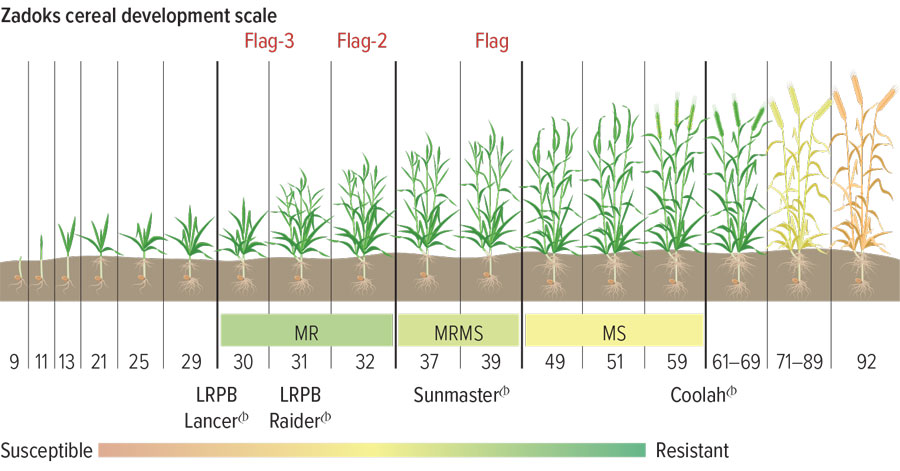

In an MR variety such as LRPB Raider, he said, adult plant resistance started at growth stages 30 to 32 (Figure 6).

“For an MRMS variety like Sunmaster, adult plant resistance activates at growth stage 37 to 39, while for MSS varieties like Coolah, this resistance kicks in around growth stage 61 to 75.

“Applying a foliar fungicide at key growth stages two to three weeks before adult plant resistance becomes active in seasons conducive to stripe rust development is the ultimate aim of an integrated approach to disease management.”

Keeping the top three leaves green was key to producing high wheat yields. Foliar fungicides only protect emerged leaves for two to three weeks after application.

Figure 6: The spray dilemma of stripe rust.

Note: MR = moderately resistant, MS = moderately susceptible. Flag-3 means the plant has developedto the first node on the main stem and three leaves below the flag leaf. Flag-2 means the second nodeis visible on the main stem, and two leaves below the flag leaf have emerged. Flag represents whenthe flag leaf becomes visible on the main stem.

Source: Steven Simpfendorfer, NSW DPIRD and GRDC

The nitrogen effect

Dr Simpfendorfer said high soil nitrogen levels complicate decisions. “When a paddock has elevated nitrogen levels, such as after a pulse crop or when large amounts of urea have been applied upfront, an MR variety will perform like an MRMS variety because high nitrogen levels delay the expression of adult plant resistance.

“Accordingly, you need to adjust your fungicide management strategy in wheat crops with higher nitrogen status and treat them as if they had one category lower level of genetic resistance.”

One option suggested, especially in more susceptible wheat varieties, was treating starter fertiliser with the fungicide flutriafol to protect the crop to growth stages 31 to 32. This approach significantly reduces early stripe rust pressure in more susceptible crops and within a localised area if used widely by growers, as stripe rust spores are readily windborne.

Correct identification

Dr Simpfendorfer said most disease management enquiries in 2024 related to identifying whether stripe rust was present in MRMS crops such as Sunmaster or if leaf speckling was a crop expressing adult plant resistance.

“Many growers who had generally correctly applied their first fungicide around GS30-32 saw symptoms like Figure 7 around GS39-49 and wanted to know what to do because they thought stripe rust was still active in their crops.

“But in the case of Figure 7, stripe rust was not rampant; adult plant resistance had taken out the infections, and a small amount had very limited pustule formation. It was a case of trusting the variety’s genetic resistance and refraining from applying another fungicide when adult plant resistance was active and had it covered.”

Figure 7: Adult plant resistance.

Source: Mark Goddard

Disease management

Dr Simpfendorfer said the random survey data pointed to the value of starting with a solid base of varietal resistance.

“More than 60 per cent of the wheat varieties grown north of Dubbo are RMR to stripe rust, which is pleasing,” he says.

He said integrated fungicide management tactics for stripe rust included:

- managing the green bridge by controlling volunteer wheat plants;

- avoiding sowing susceptible wheat varieties;

- sowing at the best time to avoid or tolerate disease without compromising yield potential;

- managing infection in dual-purpose wheat varieties to reduce pressure on main season plantings;

- considering the use of flutriafol on starter fertiliser in higher-risk varieties and situations to delay epidemic development;

- crash grazing of dual-purpose wheat varieties to reduce disease pressure;

- considering the potential for mixed infection of crop with other wheat fungal pathogens (for example, Septoria tritici blotch or wheat powdery mildew) known to have compromised resistance status; and

- rotating and mixing fungicide modes of action where possible. Rotate Group 3 DMI fungicide actives within and across seasons. Avoid applying more than three applications containing Group 3 DMI fungicides per growing season. Avoid using Group 7 SDHI and Group 11 QoI fungicides (seed dressing and foliar) more than once a season in each crop.

Dr Simpfendorfer said growers and their agronomists could contact him or NSW DPIRD cereal pathology research officer Brad Baxter for free assistance with diagnosing cereal diseases and appropriate management advice throughout the season.

*GRDC supported the forum that was hosted by the Centre for Crop and Disease Management at Curtin University, the Australian Herbicide Resistance Initiative at the University of Western Australia, and Cesar Australia. The forum was held in November 2024 near Toowoomba, Queensland.

More information: Steven Simpfendorfer, steven.simpfendorfer@dpi.nsw.gov.au; Brad Baxter, brad.baxter@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Resources: