Key points:

- Traditional planting windows are being questioned in a bid to respond to Australia’s variable and changing climate and the seasonal opportunities it presents

- Across the northern region, researchers are working on sorghum, soybeans, chickpeas and wheat to develop and evaluate new genetics, along with new agronomic practices

- This work will give growers greater options and flexibility for crop choice, improving overall farming systems’ resilience amid climate change

- Optimising agronomy with the appropriate planting time can help raise yields by improving access to moisture and avoiding stress during critical growth phases

Identifying a crop’s recommended planting window used to be easy – just stick with the traditional guides. Where it is becoming more ‘interesting’, says grains researcher Loretta Serafin, “is when you push the boundaries – planting significantly earlier or later to respond to changing seasonal conditions or opportunities”.

The NSW Department of Primary Industries researcher is one of several crop scientists tweaking traditional planting windows to boost the grains industry’s resilience amid climate change, while closing the yield gap.

Their work on crops such as sorghum, soybeans, chickpeas and wheat aims to develop and evaluate new genetics and agronomy practices which expand planting opportunities and give growers greater flexibility in crop and variety choice. Working with the climate, the goal is to avoid, or reduce, crops’ stress periods during critical crop development phases.

Mick Bange, national GRDC senior manager for agronomy, soils, nutrition and farming systems, says analyses show the climate is warming, especially during the northern region’s summer. “This brings both challenges and opportunities,” he says.

“Certainly, season lengths have changed, and this means that planting date recommendations need to be evaluated. But changing planting times also needs to consider broader system issues. For example, sometimes changing the timing of crop growth can be beneficial, but it can also be beneficial for weeds and diseases. So, it is important to capture these effects too.”

The following crops are examples of where GRDC is investing in understanding how changing planting dates may improve resilience to climate change in the northern region.

Early sown sorghum opportunities

Part way through a five-year research project across the Liverpool Plains and north-western NSW, western, southern Qld and central Queensland, Ms Serafin has tweaked planting dates for summer crops, primarily focusing on early sown sorghum.

“Across north-western NSW, the impacts of heat and drought have been at the forefront of growers’ minds for the past few years,” she says. “These conditions have meant less opportunities for sowing in the traditional window and increased heat stress at flowering and grain fill, which has reduced grain yield and quality.

“Even the Liverpool Plains, often considered the land of opportunity when it comes to summer crop selection, has seen increasing climate variability, rainfall and temperature fluctuations. These have brought new challenges, with questions over the most reliable and productive way to ensure summer crops remain profitable in the system and the impact of heat, in particular, is minimised.”

This situation is replicated across other parts of the northern region, where Professor Daniel Rodriguez and Dr Joe Eyre from the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation and Darren Aisthorpe from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries have been working with Ms Serafin on sorghum and early planting under a joint investment with GRDC.

Ms Serafin says varying sowing windows brings both risks and opportunities across all parts of the northern region when responding to climate change. However, the largest influence in all decisions is stored soil moisture. “Deciding to plant with less than a full profile immediately increases the risk of reduced crop yields or failure, and ultimately profitability, unless you can be ‘under the right cloud’ during the season, regardless of the sowing date.”

NSW DPI’s sorghum trial at Moree in the 2018/2019 season. The team has investigated two alternatives – moving the sorghum planting window forward by four weeks, and extending the planting window to include the end of January and early February. Photo: NSW DPI

Broadly speaking, the NSW DPI team has investigated two alternatives – moving the planting window forward by four weeks, and extending the planting window to include the end of January and early February. The work has found the following:

Early sowing:

- is possible in soil temperatures as low as 12°C, provided there is sufficient soil moisture; however, it increases the risk of patchy and reduced establishment if cooler-than-predicted temperatures or frosts occur in the two weeks post-sowing;

- has more applicability when soil temperatures are 14°C and rising, a temperature that is still significantly earlier than traditional recommendations;

- reduces the risk of high temperatures and heat stress during flowering; and

- provides a longer period to refill the soil water profile following the earlier crop harvest, increasing the likelihood of a double crop option.

Late sowing:

- brings more theoretical risks than sowing early;

- occurs in the heat of summer, so seedbed temperatures are hotter, possibly influencing establishment, and seedbed moisture will decline faster; and

- may mean watching several sowing opportunities pass by over the preceding spring and summer.

With a lack of rain during the past summer, the NSW DPI team also decided to research just how long planting can be delayed, taking the opportunity to plant sorghum, sunflowers and maize at the beginning of February at Breeza on the Liverpool Plains.

“Many of the issues anticipated occurred,” Ms Serafin says. “The sorghum was affected by midge and ergot, the sunflowers were predated by birds and were severely damaged, while all three crops took a long time to reach physiological maturity and harvest ripeness.”

Late sowing will likely remain a last resort, when cashflow is needed and other options have passed, she says. The numerous risks include slow dry down and delayed harvest, clashes with winter crop planting, and frost terminating the crop before maturity.

The sorghum crops at Bogamildi, near Moree in mid-October 2020. The crops on the left were sown earlier than the ones on the right. Photo: Loretta Serafin, NSW DPI

The sorghum crops at Bogamildi, near Moree in mid-October 2020. The crops on the left were sown earlier than the ones on the right. Photo: Loretta Serafin, NSW DPI

Dr Eyre says the Queensland trials helped support the trend among growers to advance sorghum planting times.

He says the biggest benefit from the research is that sorghum can be planted much earlier without yield penalty and this provides opportunities for increasing double cropping in some regions.

However, the highest-quality seed must be sown into a seedbed that remains moist until the seedling emerges, which could be two weeks. Only fields with low weed, disease and pest pressures should be considered.

Additionally, an early sowing date allows the ratooning of sorghum in irrigated systems, which provides an alternative to cotton, particularly in seasons with low water availability.

Further research on sorghum growth, development and root function in suboptimal temperatures is ongoing to quantify production risks for early sown sorghum yield potential.

Heat-hardy chickpeas a summer option

While wandering through her chickpea breeding plots on a typically hot October day a few years ago, plant breeder Dr Angela Pattison started questioning why this heat-tolerant legume is grown when it is.

Around Narrabri, where Dr Pattison works at the University of Sydney’s Plant Breeding Institute, this crop is traditionally planted in winter. That means its reproductive, or pod-filling, stage occurs in the lead-up to summer, an environmentally stressful time.

“It was quite warm, and I thought – ‘wouldn’t it be smart for the plants to fill their pods in the milder parts of the year?’”

Dr Pattison was already working with heat-tolerant breeding material, selected from lines in the Legumes for Sustainable Agriculture (LSA) program, when local grower and agronomist Drew Penberthy approached her with an idea – summer-sown chickpeas. “It was a case of research ideas colliding,” Dr Pattison says.

Mr Penberthy had returned from India, where at least two chickpea crops a year are planted. “Chickpeas have been cropped for thousands of years in India,” he says. “They have cultivars suited to hot starts, which can grow in a short window and finish when the weather is cooler. It is something we are interested in.”

Summer chickpeas would give growers an option in a wet summer. “Chickpeas are the most drought-hardy of the legumes. And the theory for us is that if we get a wet summer or harvest, we should plant something. Chickpeas give us ground cover and herbicide options to control hard-to-kill weeds.”

Dr Pattison says initial small-scale trials using new germplasm did “amazingly well” under the harsh 2019 late summer/early autumn conditions and a larger trial in 2020 ensued.

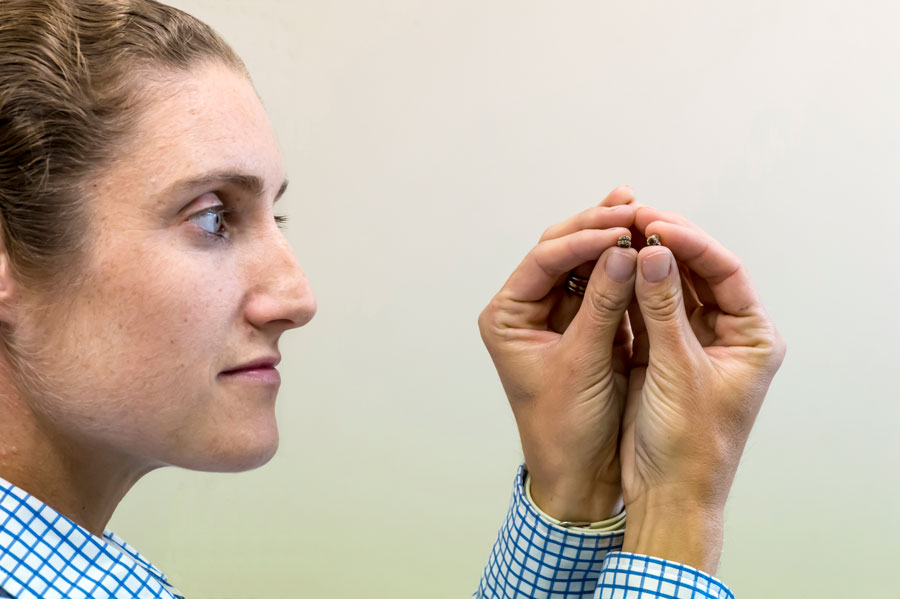

University of Sydney plant breeder Dr Angela Pattison started questioning why this heat-tolerant legume is grown when it is, winter. Her work has since looked at summer options, showing the ability to start flowering and podding quickly is key. Photo: Nicole Baxter

The lines chosen were short-season, had good yield potential and were potentially photoperiod-insensitive. This means they ignore shortening day lengths, as opposed to photoperiod-sensitive types, which respond to shortening day lengths by focusing on stem growth and branching.

“I was uncertain which ones would be photoperiod-insensitive until putting them under decreasing day lengths. Some have turned out to yield more than 30 per cent higher than the winter-bred commercial cultivars in a summer-planted situation.”

Dr Pattison says the lines needed to be short season to take into account planting conditions. “Summer planting would not work for genotypes that needed a long vegetative phase. That would mean they would need to be planted too early in the year and hence get too stressed during February.”

Honours student Prue Gordon, who has been working with Dr Pattison, says management will be crucial for successful summer chickpeas. A strict planting schedule is also needed to cope with soil temperatures of up to 50°C. “They need to be planted when it has just rained or when it is going to rain, even with good subsoil moisture.”

Dr Pattison says another consideration is ‘plasticity’. “Winter-sown chickpeas have been developed to be ‘plastic’. They have been designed to respond to rainfall and keep producing. We don’t want summer ones to do that. Instead we want them to start and finish on time.”

The work has shown there is a clear relationship between how long it takes for plants to flower, either via flowering genes or photoperiod-sensitivity genes, and yield.

“The ability to start flowering and podding quickly is the key. This is one of the reasons why breeding varieties which are suited to a summer planting time is essential,” Dr Pattison says.

“Many of the breeding lines tested in this trial only have mediocre performance in winter because they are not plastic. They do not put effort into branching during the cooler months, and finish podding. Their counterparts, suited to winter, still stack on flowering nodes. However, the very traits which make them able to yield well in winter are a disadvantage with a summer planting date.”

At the moment, a summer chickpea season would most likely only work in certain growing areas. “It will not be successful in parts of Queensland where the heat persists too long beyond summer. And it is less likely to work further south because it is too cold by early April for flowers to fertilise.”

However, climate change will alter that, particularly if the evening temperatures become milder.

The work has seen Dr Pattison’s team trial genotypes from around the world, including India, plus some breeding material and Australian cultivars. “But with 44 genotypes in the trial, we only scratched the surface. I am confident there are even-better-suited lines than the ones we trialled, and they won’t be hard to find.”

There are further R&D opportunities. The summer chickpea team encourages interested parties to contact GRDC for more information.

LSA is an Australian Research Council project. GRDC is an industry partner. Visit Legume Hub for more information.

Synchronising wheat with seasonal patterns

Although wheat varieties grown in Australia are not broadly adapted to the environment or management, growers can still optimise grain yield via variety selection and management.

In research led by Dr Felicity Harris from NSW DPI, various wheats were tested across 10 locations in the northern grains’ region. They included slow-developing winter types to fast-developing spring types. The aim was to provide growers with regional information about variety adaptation and recommended sowing times.

Dr Harris explains that across the northern region, one of the primary drivers of yield and grain quality is flowering time. Synchronising crop development with seasonal patterns means flowering occurs at an optimal time.

“This period is a trade-off between increasing drought and heat threat, and declining frost risk. Across the region, the optimal flowering period varies from late July in Central Queensland to mid-to-late October in southern NSW.

“There is no ‘perfect’ time to flower when there is no risk, rather there is an optimal period based on minimising risks, and maximising grain yield based on probabilities from previous seasons.”

Dr Felicity Harris from NSW DPI is testing various wheats 10 locations in the northern grains’ region to provide growers with regional information about variety adaptation and recommended sowing times. One of the primary drivers of yield and grain quality in the region is flowering time. Synchronising crop development with seasonal patterns means flowering occurs at an optimal time. Photo: Nicole Baxter

Planting opportunities

Dr Harris says that because seasonal breaks are highly variable, matching flowering date to a growing environment can be a challenge.

To determine planting probabilities, a simulation using ‘sowing rule’ methods was undertaken. (The rules are from University of Adelaide researcher Murray Unkovich. His work is called ‘A simple, self-adjusting rule for identifying seasonal breaks for crop models’.)

According to this rule, Dr Harris says, sufficient seedbed moisture to establish a wheat crop creates a planting opportunity. And this differs across environments.

In her research, this showed that the probability of a sowing opportunity at Condobolin, in central west NSW, prior to 25 April, was 38 per cent across 2000 to 2018. This compared to 65 per cent across the same years at Yarrawonga, further south.

“As such, there are limited opportunities to sow a winter wheat at Condobolin. However, this probability increases to approximately 70 per cent by early May and the opportunities increase for mid-fast developing varieties.

“In contrast, growers in Yarrawonga have more flexibility in their sowing window and could consider incorporating slower-developing or winter types for earlier sowing in their program.”

Because sowing opportunities will influence variety choice and sowing time, growers can use this information to optimise yield.

Soybeans adapted to suit conditions

Early work to adapt US-bred soybeans to Australian conditions, a process that began 25 years ago, is still having an effect now, helping breeders to continue to broaden soybeans’ geographic and seasonal range.

That initial work, CSIRO’s first GRDC-funded project with soybeans, simulated the plant’s juvenile genes to delay flowering and reproductive development to suit Australian locations and planting dates. Yielding well, further breeding work ensued.

Soybean variety Kuranda HB1, bred by CSIRO breeder Dr Andrew James, is widely adapted. It shows high yields in the tropics in both wet and dry seasons. Photo: Andrew James, CSIRO

Soybean variety Kuranda HB1, bred by CSIRO breeder Dr Andrew James, is widely adapted. It shows high yields in the tropics in both wet and dry seasons. Photo: Andrew James, CSIRO

Soybeans are photosensitive. CSIRO soybean breeder Dr Andrew James, who leads the GRDC-supported National Soybean Breeding Program, explains their trigger to flower and mature occurs when the days shorten.

By stripping out just the right number of photosensitivity genes and replacing them with photo-insensitive juvenile genes, more broadly adapted soybean varieties have been created.

The latest are the recently released soybean varieties Kuranda HB1, New Bunya HB1 and Mossman HB1. They are broadly adapted. For example, Kuranda HB1 shows high yields in the tropics in both wet and dry seasons. In the Burdekin, the varieties can be planted from December through to mid-July, although the actual window is potentially wider than that. However, Dr James says the risk of hot, wet weather damaging grain quality at harvest time may be too high.

A broad adaption does not suit all regions. For example, in traditional US growing regions, breeders have produced excellent varieties using narrow adaptation, with some varieties suited to geographic ranges of only a few hundred kilometres north or south.

Dr James says this narrow range does not suit Australian soybean growers. “Our planting dates can be all over the place due to variability in cropping systems. Planting opportunities arise in response to rainfall and we have an extended north–south range to our cropping environments.

“So, we need a wider planting window and varieties that have a far greater north–south adaptation, which is what we have produced – varieties adapted to a wide geographical and planting window.”

More information: Loretta Serafin, 0427 311 819, loretta.serafin@dpi.nsw.gov.au; Dr Joe Eyre, 0467 737 237, j.eyre@uq.edu.au; Dr Andrew James, 07 3214 2278, andrew.james@csiro.au; Dr Angela Pattison, 02 6799 2253, angela.pattison@sydney.edu.au; Farming Systems Research Group, Twitter @Queensland_fsr