Increasing chickpea production in Australia requires enhancing chilling tolerance in the species through the exploration of greater trait diversity in its wild relatives.

Established production regions for chickpeas are in the relatively warm areas of northern New South Wales and southern Queensland. To expand production of the pulse to cooler southern and western regions, improved chilling tolerance at flowering is required. Incorporating this trait could also stabilise yields in northern regions experiencing radiation frosts.

Chilling is a significant stress on chickpeas because at flowering it disrupts fertilisation and pod set, delaying the reproductive phase, exposing plants to greater heat and drought stress later in the season, which decreases yield while increasing risk.

The challenge

Low genetic diversity constrains chickpea improvement by limiting variability for traits of interest. This is particularly the case for reproductive chilling tolerance, which delays pod set in chickpeas, exposing the crop to terminal drought throughout Australia, reducing yield and yield stability.

This reflects domesticated chickpeas’ unique evolutionary history whereby the crop escaped winter stress in both space and time, moving from West to South Asia (Indian subcontinent) in the Bronze Age and returning as a spring-sown crop.

In contrast, its close wild relatives are true winter annuals that germinate with the autumn opening rains in low-temperature habitats in south-eastern Turkey and have greater than 100-fold genetic diversity than domesticated chickpeas. While this combination suggests great potential for improving domestic chilling tolerance, until recently there were very few wild accessions to work with.

This changed with recent collection efforts supported by GRDC, the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture, a range of Turkish universities and the University of California-Davis with CSIRO in South-East Anatolia, returning to Australia with hundreds of wild accessions that can be crossed with domestic chickpeas.

This collection includes 229 Cicer echinospermum and 484 Cicer reticulatum accessions, the latter two species being wild relatives of the domesticated chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Notably, the team also discovered a Cicer species new to science, now known as Cicer turcicum, which appears to have very-high heat tolerance and resistance to bruchids.

The wild collection has subsequently been screened for low-temperature flowering, podding and pod production rate in both Turkey and Australia and identified tolerant lines that have been crossed into CBA Captain .

These populations are currently under development and have not yet been screened for low-temperature tolerance. However, researchers have been able to screen a large wild by domestic diversity panel created earlier by Curtin University, which crossed the most diverse C. echinospermum and C. reticulatum collected in 2013 with PBA HatTrick .

Reproductive chilling tolerance screening is carried out in the field in cool locations at Mount Barker, Western Australia, and Wagga Wagga, NSW. The trials are hand-sown early using vernalised seed and artificial lighting to prompt early flowering when temperatures are low.

The results are promising. The data demonstrates that wild Cicer is more cold-tolerant than chickpeas, with much more stable phenology, higher growth rates, earlier pod set and higher rates of low-temperature pod production.

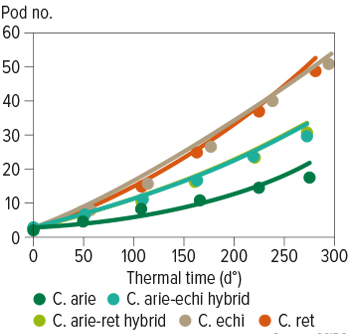

At Mount Barker in 2021, average low-temperature (<13.4oC) pod production rates were almost three-fold greater in wild Cicer than domestic chickpeas while the wild cross domestic hybrids were intermediate between the two (Figure 1). Importantly, Figure 1 shows that it is possible to cross this tolerance into chickpeas, even in a population designed for maximising genetic diversity, rather than cold tolerance. Indeed, some of the wild cross domestic hybrids have low-temperature pod production rates as high as the most-tolerant wild Cicer accessions.

Figure 1: Mean responses of wild, wild cross domestic and domestic species of chickpea to chilling temperature in the field at Mt Barker, Wester Australia 2021.

Source: CSIRO

These results are very consistent across years; the same species performance was observed at Mount Barker in 2022 and stable resistance was identified among wild and wild cross domestic hybrid accessions.

Work is ongoing to better understand both the temperatures responsible for chilling stress and wild and domestic responses to these, as well as their underlying genomic basis. The work so far suggests that day temperatures are likely to be more important than night temperatures, which will have significant implications for where chickpeas can be grown.

More information: Dr Jens Berger, [email protected]