Key points

- Despite rising prices, nitrogen’s use could still be economically sound

- Even with urea prices exceeding $1350/t, growers would still expect to generate $1.85 in income for every dollar spent on nitrogen at average grain prices

- High grain prices will offset high nitrogen costs

- James Hagan from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) has run analyses into fertiliser economics and spoke about them at the recent GRDC Updates

For many, the thought of rising nitrogen costs is hard to bear. However, even if prices tripled, nitrogen’s use could still be economically sound.

James Hagan from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) talked through research into fertiliser economics at the GRDC Updates.

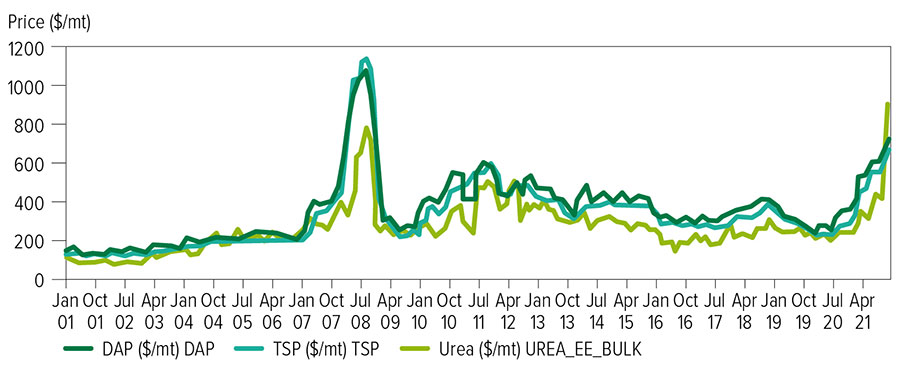

The 2021-22 period has seen a rapid and large increase in pricing. “Urea prices rose by more than 200 per cent, while diammonium phosphate (DAP) and monoammonium phosphate (MAP) rose by more than 100 per cent in the 12 months to November (Figure 1).”

He said current prices pose a decision-making challenge. “This is especially so given that many growers may have paddocks with low nitrogen levels following 2021’s high-yielding winter crops.”

At average fertiliser costs, return on nitrogen investment exceeds 5:1. That is, every dollar spent on nitrogen results in $5 of additional profit.

Yet despite urea prices tripling to more than $1350 a tonne, growers could still expect additional income of $1.85 for every dollar spent on nitrogen, if the rule of thumb that each tonne of grain uses 40 kilograms of nitrogen.

“However, whether fertiliser is priced at $450/t or $1350/t, understanding why it is being applied is essential. Specifically, what are you trying to achieve in terms of both yield and protein, how will the application of fertiliser help you meet that goal, and what is the impact of that on profit?”

James Hagan from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland (DAF) has run analyses into fertiliser economics. Photo: Supplied by James Hagan

High fertiliser prices increase the economic importance of nutrient decisions, Mr Hagan says. “Finding the appropriate nutrition application rate will have a greater impact on profit than in years with more typical prices.

“Having a good understanding of your existing nitrogen levels through soil testing is now worth at least three times as much in 2022 as previous seasons. High prices also make practices that improve efficient use of nitrogen more important to consider, with savings via variable rate and budgeting or applying fertiliser to better-match crop demand more critical.”

Figure 1: Diammonium phosphate (DAP), triple superphosphate (TSP) and urea prices ($USD), 2001–21 (World Bank).

Urea prices rose by more than 200 per cent, while diammonium phosphate/monoammonium phosphate by more than 100 per cent in the 12 months to November 2021 (Figure 1). Source: James Hagan, DAF

Yield calculations

Using CropARM, a tool that simulates input options and risk, Mr Hagan compared different nutritional strategies across possible seasonal conditions to estimate yield scenarios.

“Past research has shown that soils in northern farming systems typically mineralise between 50 kilograms per hectare and 100kg/ha of nitrogen over the summer months. With good summer rain across many regions, we can assume largely full profiles of moisture.”

Mr Hagan said this was supported by the CliMateApp, which suggested farms had 88 per cent full profiles from rainfall over late spring and early summer throughout much of southern Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Using this information and assuming 50kg/ha of mineralisation, he contrasted the expected yield results of applying no nitrogen, 50kg of nitrogen/ha and 100kg of nitrogen/ha to soil with 150 millimetres plant-available water capacity (at 90 per cent capacity or 135mm), on 30 April at Moree.

It showed that with no nitrogen applied, the expected median yield was 1.5 t/ha, at 50kg N/ha this became 2.5 t/ha and at 100kg N/ha median yield was 3.2 t/ha.

Gross margin analysis

Mr Hagan’s next step was to calculate what this meant in terms of rising urea prices, while keeping other inputs consistent.

The analysis used:

- A 10-year average wheat price ($295/t);

- average urea and MAP prices of $450/t and $800/t, respectively;

- November 2021 prices for urea and MAP of $1350/t and $1800/t, respectively;

- three application rates – no nitrogen, 50kg of nitrogen/ha and 100kg of nitrogen/ha;

- a predicted median yield of 3.2t/ha from a full profile with 100kg of nitrogen applied; and

- an applied nitrogen recovery rate of 60 per cent in a year with average costs, which leads to a gross margin of more than $450/ha, using historical pricing.

With the same inputs, yields and grain prices, the gross margin for 100kg of nitrogen/ha at current input prices would be more than halved to just $124/ha in 2022, he found (Table 1).

However, before growers start applying less fertiliser, he said it was important to note that this is dependent on grain prices. “Futures grain prices have hovered between $500 and $650 per tonne in Australian dollars.

“At prices being witnessed on the futures market, our expected gross margins this year with a median yield of 3.2t/ha are higher than the $450/ha expected under average input pricing and grain price scenarios.”

However, Mr Hagan concedes that predicting wheat prices at harvest remains challenging. “And the risks for producing this year’s winter crop are also increased, with events such as hail and frost leaving growers exposed to much higher variable costs.”

Additionally, when using conservative prices and yields, there are scenarios where negative returns to fertiliser applications are possible. “However, with good yields or above-average prices, like we’re seeing in the current market, positive economic responses to nitrogen are still possible in 2022.

What this means is that nutrition decisions should continue to be driven by underlying agronomic principals of source, timing, rate and placement, he says.

“It is worth keeping in mind that the analysis in this paper has focused on nitrogen responses in a single season. There are legacy system impacts to fertiliser application which may only be observed in future years.

“For example, wider adoption of pulses will result in lower ground cover and future fallow soil water accumulation, or lower fertiliser application rates may result in a faster decline in soil organic matter, which will have impacts on soil nitrogen mineralisation for years to come.”

More information: James Hagan, 0476 828 018, james.hagan@daf.qld.gov.au; Queensland Government - ARM Online; Australian CliMate