Ongoing research reveals that insect resistance to phosphine is strengthening, making the control of stored grain pests increasingly more challenging.

The GRDC’s national monitoring and management program has found that, over the past five years, insect pests have become harder to control with the fumigant used widely in on-farm storage.

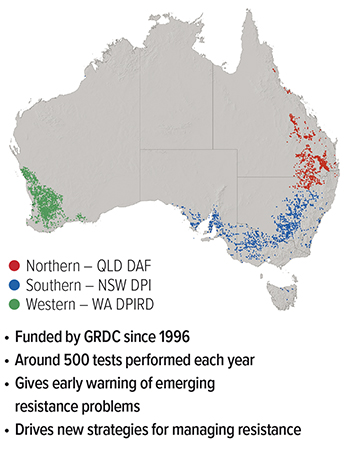

The program, which has been running for more than two decades, conducts more than 500 tests on insects each year from Australia’s cropping regions.

This helps to build a broad picture of emerging and changing resistance, while also offering individual growers practical advice on how to manage an infestation should resistance be detected in samples they have submitted for analysis.

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries’ (QDAF) Dr Manoj Nayak leads the GRDC program.

He says that phosphine is accepted globally as a ‘residue free’ treatment. “It is the cheapest and most versatile among the currently available treatments, and has a long history of success in controlling major pest species of stored commodities, making it the ‘treatment of choice’ for industry,” Dr Nayak says.

Although we have seen strong levels of resistance developed to phosphine across key pest species over the years, we are successfully keeping their frequencies to a minimum level in Australia through the implementation of a nationally adopted resistance management strategy.

“Early resistance detection, strength characterisation and timely implementation of intervention strategies involving alternative treatments, such as sulfuryl fluoride and grain protectants, are key to the success of this strategy.”

QDAF entomologist Dr Brodie Foster says an early warning about resistance problems is a benefit. “They might be developing in particular parts of Australia or particular species,” he says.

“And we can then incorporate those warnings of problems into our research and come up with alternative strategies.”

Dr Foster says that when the program started in 1996, it was “the norm” to easily control susceptible infestations with phosphine. Today, higher concentrations of phosphine are required and for a longer period to control even weakly resistant insect populations. More populations with strong phosphine resistance are showing up.

GRDC resourcing priorities

For GRDC grower relations manager Graeme Sandral and manager, pests, Leigh Nelson, resourcing priorities for the national resistance monitoring and management of stored grain pests program are focused on three areas:

- maintaining grain quality and price post-harvest;

- ensuring export markets are protected; and

- maximising the life and efficiency of grain protectants and fumigants.

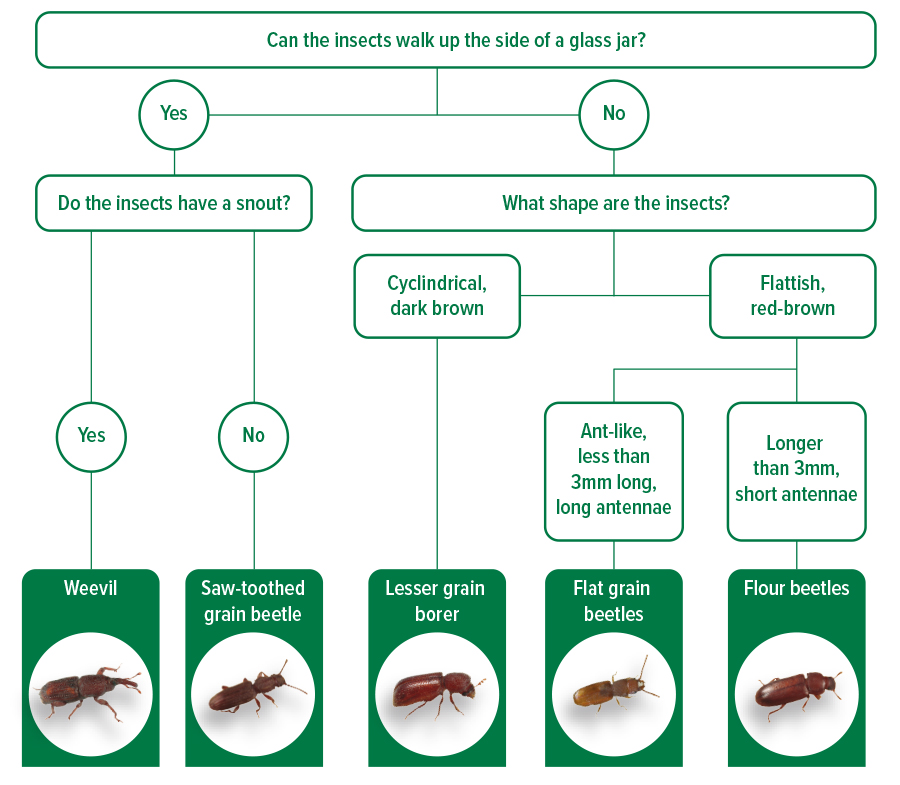

Figure 1: Identification of common pests in stored grain

Source: QLD DAF

Northern and southern regions

In both the northern and southern growing regions, highly resistant populations of flat grain beetles (Cryptolestes spp.), known as the ‘rusty grain beetle’ (C. ferrugineus), have emerged as the biggest concern.

Dr Foster says four out of five flat grain beetle species can still be controlled “fairly easily”, providing fumigation is undertaken according to label instructions and in a gas-tight sealable storage. However, it is proving increasingly difficult to control highly resistant populations of rusty grain beetles with phosphine.

Strong resistance to phosphine has been detected in “nearly every” sample of the rusty grain beetle submitted to the program for analysis by bulk handlers over the past five years.

Dr Brodie Foster, DAF. Photo: Melissa Marino

Dr Brodie Foster, DAF. Photo: Melissa Marino

Meanwhile on-farm, data from the northern and southern regions showed 2023 was the worst year on record for phosphine resistance. “The problem is that rusty grain beetle populations are proving difficult to control, even with an excellent fumigation process,” Dr Foster says.

Also highlighted as a cause for concern across southern and northern regions is the lesser grain borer (Rhyzopertha dominica) – an insect that develops inside the grain kernel and can cause significant damage.

Dr Foster says tests show that strong resistance to phosphine in the lesser grain borer has been steadily increasing over five years. He says 2023 was the worst year on record, with one in two samples from the north showing strong resistance to phosphine and a similar result in the south.

More variation was found between the northern and southern regions in relation to other species. The rust red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum), for example, showed strong resistance in the north but not in the south, while in the south the rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae) was more of a problem than in the north.

These results “showing different patterns in different regions emphasises the importance of widespread testing”, Dr Foster says.

Western region

In Western Australia, the red flour beetle is the major concern for on-farm grain storage; however, rice weevil is a significant storage pest in the southern parts of the state and bulk-handling facilities.

During a recent GRDC grain storage webinar, David Cousins – grain storage expert with the WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (WA DPIRD) – said it was not known why the prevalence of different grain insects differed in these facilities.

“We do, however, know that resistance to phosphine is on the rise for several grain storage insects, although not to the extent in the eastern states. Weak resistance to phosphine, in particular, is on the rise and red flour beetle is the major culprit. Weak resistance is approaching 80 per cent in samples we have tested.”

Mr Cousins said phosphine was still an effective tool in gas-tight sealable storage but regular testing should be undertaken to monitor resistance levels. Affected western grain samples must be sent to WA DPIRD.

Figure 2: Prevalence of insect species in 2024.

Source: QLD DAF and WA DIPRD

What to do

To help control pests in stored grain in the face of growing resistance, growers are urged to identify the insect species correctly in the first instance. This helps to pinpoint whether the infestation is due to the likelihood of strong resistance or because silos are not as gas-tight as they should be. This often results in sublethal applications contributing to resistance development. Knowing this would inform the appropriate action to take.

Options include pressure-testing the storage to check it is gas-tight sealable, monitoring gas concentrations during the fumigation and/or rotating phosphine use with sulfuryl fluoride applied by a commercial fumigator as a ‘resistance breaker’.

“Often when we talk about grain pests on-farm, we just refer to them all as weevils,” says Chris Warrick, GRDC grain storage extension specialist. “But there are about five or six main species with quite different profiles of resistance, so it’s worth understanding what insect you’re actually dealing with, particularly if fumigation has failed.”

Identifying insects correctly also helps to inform which grain protectants to apply to the following year’s grain based on what insects are already present on the farm, QDAF’s Dr Foster adds.

The GRDC Grain Storage Extension team says resistance is also increasing for protectants, so it recommends rotating between the two main chemistries (spinosad or deltamethrin plus s-methoprene) each year or two to help slow this process.

Figure 3: The ‘National Phosphine Resistance Monitoring’ program

Source: QLD DAF

To extend protection to include the rice weevil, chlorpyrifos-methyl or fenitrothion must also be included. But if the lesser grain borer is detected, growers should use spinosad over deltamethrin, Dr Foster says. This is because QDAF research has shown resistance in the lesser grain borer to deltamethrin. “Ideally, a three-way combination of spinosad, s-methoprene and either chlorpyrifos-methyl or fenitrothion would guarantee the complete control of resistant populations of all major pest species,” Dr Foster says.

Markets also need to be considered in the context of grain protectants as well as ensuring products are registered for the type of grain being stored. Fenitrothion is accepted in more overseas markets and is registered for malt barley but has a longer withholding period (90 days) compared with chlorpyrifos-methyl, which is better suited to domestic feed cereals with nil withholding.

In Western Australia, the availability of grain protectants has been limited as most of the crop is exported and export markets are reluctant to accept grain treated with protectants.

In 2024, deltamethrin is registered for use in WA but no rotation option and no mixing partner is available that is effective against rice weevil. In some instances, protectants could help WA growers store stockfeed in unsealed storage, but broad spectrum protection is not available.

Caution should be exercised with the use of this protectant, says WA grain storage expert Ben White, due to export markets’ averse response to its use and the fact that there is no other protectant with which to rotate the use of deltamethrin.

“It is good to have more options, but you need to be conscious of their limitations,” Mr White says.

On-farm essentials

An appropriate grain protectant strategy is one of the “on-farm essentials” important to effectively control insects in the face of growing resistance, particularly for unsealed storage where fumigation is not an option, GRDC’s Chris Warrick says.

Other key measures include:

- Pressure-test silos to ensure they can hold sufficient gas concentrations. Silos that are sold as ‘gas-tight’ still need maintenance and follow-up pressure testing.

- Recirculate gas in large silos (300 tonnes or more) to ensure adequate concentrations are achieved in all areas, and always follow label directions.

- Send a sample for resistance testing to the GRDC phosphine resistance monitoring program if insects survive fumigation.

- Rotate phosphine with sulfuryl fluoride, sold as ProFume® or Zythor® (there is no known resistance to this fumigant worldwide).

Prevention better than cure

In general, Dr Foster says prevention is always better than a cure.“We speak to some growers who haven’t done phosphine fumigations in years because they are really focusing on prevention,” he says.

The key elements of a solid prevention strategy include:

- good hygiene around the farm and in farm machinery that handles grain as well as cleaning silos by disposing of all residual grain;

- structural treatments such as diatomaceous earth (fossilised algae), also known as DE or Dryacide®;

- grain protectants;

- aeration cooling; and

- regular monitoring.

Dr Foster says many insects cannot complete their life cycle below about 15°C, so lowering the grain temperature can help to prevent infestations.

Mr White says aeration provides big opportunities to improve grain storage for growers in the west, but up until now there has been low adoption. “Adoption is as low as five per cent of growers in the west as compared to 80 per cent in eastern states,” he says.

“Often, the issue is the lack of access to power in remote regions. However, generators are well worth considering,” he says. “Also consider the types of fans used. We determined from research that brushless fans perform better.”

For any questions regarding insects in stored grains, growers are urged to contact the GRDC Grain Storage Extension team on 1800 WEEVIL.

For free testing of insects that have survived fumigations, growers are encouraged to send samples to QDAF (northern region), NSW DPIRD (southern region) or WA DPIRD (western region).

Instructions for insect resistance testing can be found on the Stored Grain website.

Tristan Nitschke says storage provides his farming operation with flexibility. Photo: Lucy RC Photography

Weather vs climate

For northern grower Tristan Nitschke, who farms on Queensland’s Western Downs, his family’s on-farm storage system allows for aeration, drying and, importantly, flexibility.

Grain with lower moisture content is less likely to incur insect damage. Specially engineered drying silos equipped with automated three-phase fans reduce moisture content in grains and have led to a reduction in sorghum moisture content from 16 to 12.5 per cent.

“The most efficient way to dry grain is standing in the paddock, but when that becomes threatened or compromised by time constraints or weather then you’re best to get it off,” Tristan says. “So now, even if we have harvested grain at higher moisture, we can be much more confident with the quality in the silo and ultimately what we can deliver.”

Flexibility is also provided through their spread of smaller and medium-sized silos, which allow for grain to be segregated according to protein levels, screenings and moisture. Grain can also be amalgamated on-farm as required to meet market requirements around, for example, protein or other factors.

“We get a huge benefit from segregation and being able to blend quality and be assured of what we’re delivering,” he says.

Improved pest management on-farm has given Tristan the confidence to store grain for longer, which also broadens marketing options. “So rather than send it all off to market and take what we get, we can assess what we’ve got, assess the market, and 80 per cent of the time, it’s of benefit to the bottom line.”

More information: Brodie Foster, brodie.foster@daf.qld.gov.au; Chris Warrick, chris@primarybusiness.com.au