Key points

- Exchangeable sodium percentage tests are overused

- This has led to ineffective and uneconomical soil management strategies, including gypsum use

- Errors in soil diagnosis have led to enormous potential yield gaps

An urgent rethink of how soil constraints are assessed is needed, with an over-reliance on exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP) tests said to be leading to ineffective and uneconomical management strategies.

The University of Southern Queensland’s (USQ) Professor John McLean Bennett is leading work co-invested by GRDC, USQ and the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) on ameliorating the northern region’s main soil constraints – dispersive soils and compaction.

“Traditionally, sodicity and dispersion have been used synonymously,” he says. However, not all sodic soils are dispersive and industry reliance on measuring sodicity to indicate soil instability is misplaced.

Sodicity versus dispersion

Soil sodicity is usually naturally occurring and occurs where there is a high proportion of sodium cations relative to other cations. As sodium is leached through the soil, some sodium remains bound to clay particles, displacing other cations. This can degrade soil properties by weakening the bond between soil particles.

The result can be a complete breakdown of the soil aggregate into sand, silt and clay particles.

Professor Bennett likens this to a sugar cube being broken into its individual grains. “This is known as dispersion and often results in surface crusting; a reduction in infiltration, soil water storage and availability; increased run-off; and associated poor crop emergence and yield.

“Diagnosis is often via an ESP test and if the ESP is greater than five per cent, gypsum application is recommended.”

Yet not all sodic soils are dispersive. Through the research project, Professor Bennett and USQ’s Dr Stirling Roberton assessed 61 farms. Of those, 75 per cent were considered sodic when ESP tests were used. However, only 48 per cent had dispersive soils. “This is a huge error rate,” Professor Bennett says.

“Of all soils assessed as dispersive using the ESP criterion, 38 per cent would be incorrectly diagnosed. Amendment action plans would result in total economic loss of the value of the amendments, transport, spreading and labour for these soils.

“This has economic consequences for growers who apply gypsum where it is not needed. It also erodes confidence in gypsum use.” Professor John McLean Bennett

If the farms assessed in the research had used the recommended gypsum rates, the costs involved would total almost $9 million. In comparison, the cost to directly measure dispersion would be $14,000.

“A dispersion test – a direct measure of soil stability – should become standard for on-farm soil analysis.”

Dispersion test

A dispersion test can be relatively simple, he says. A soil aggregate of 3 to 5 millimetres in diameter is placed into de-ionised water (or rainwater) and assessed for dispersion at 10-minute, two-hour and 24-hour intervals.

From this a dispersion score can be calculated indicating severity.

Professor Bennett says dispersion looks like milky coffee. “You can’t actually see the clay particles. A good way to assess whether it is dispersion is to look at the aggregate from the side. The clay particles will suspend up off the bottom of the container in a milky cloud, while small, stable micro-aggregates will remain settled on the bottom.”

Although the test can be undertaken easily at home, it requires other analysis to calculate any gypsum requirements. “So, it can be more conveniently done in the laboratory.”

Unfortunately, many laboratories do not offer the test, but Professor Bennett hopes this will change.

David West, a research technician working on the project, is undertaking a PhD on automating aggregate stability tests. The prototype robot he has developed can run hundreds of samples without human intervention once aggregates are loaded. “It removes the mundane labour and uses machine vision to accurately diagnose dispersion occurrence and extent.”

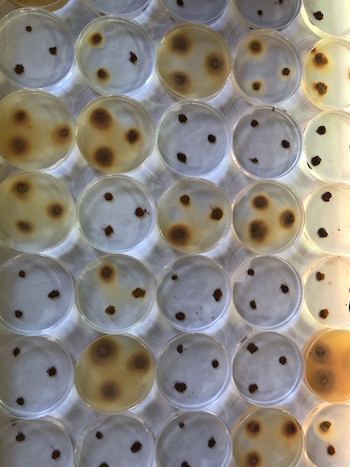

Aggregate stability tests are an important part of this soil research. This image shows how dispersive soil (cloudy water) looks compared to non-dispersive soil (clear water). Industry reliance on measuring sodicity to indicate soil instability needs to be changed because of huge error rates, leading to incorrect and expensive soil amelioration plans. Photo: Stirling Roberton

Aggregate stability tests are an important part of this soil research. This image shows how dispersive soil (cloudy water) looks compared to non-dispersive soil (clear water). Industry reliance on measuring sodicity to indicate soil instability needs to be changed because of huge error rates, leading to incorrect and expensive soil amelioration plans. Photo: Stirling Roberton

Management changes

For growers, the first management change needed is to break the association between sodic and unstable, Professor Bennett says. “A soil may be sodic, but this does not mean it will disperse.”

This would lead to better testing, diagnosis and management plans. Already, he has convinced two major agronomy companies to change their testing process, demonstrating the cost of wasted application and unrealised potential yield.

An ESP test will still be carried out – to calculate the amount of gypsum needed – but a gypsum recommendation will only be made where dispersion is observed.

Gypsum can cost up to $120 per hectare spread. “So, a lab cost with an average cost of $22.50 per sample is well justified.”

Professor Bennett says unrealised yield gaps have the potential to be enormous and soil scientists must share the blame for this inadequate performance.

“We have done a poor job in helping to implement a robust and comprehensive system for professionally assessing dispersive soil in a way that ensures that expensive gypsum and/or lime application actually does give profitable crop responses.

“I also think we place too much pressure on our agronomists, who are crop specialists first and foremost.

“We need to support agronomists with access to certified professional soil scientist services. This specialist service access is very much lacking and must be established to better serve the industry.”

The team hope to turn this around.

More information: Professor John McLean Bennett, 0438 683 426, john.bennett@usq.edu.au

Read: Lesson learned as soil tests beat costly assumptions and Ripper idea to engineer soil fix.