In brief

- Annual ryegrass resistance to Group 1 and Group 2 post-emergent herbicides is widespread across Australia

- Twenty-three per cent of annual ryegrass samples collected from New South Wales alone were resistant to glyphosate

- Fortunately, annual ryegrass resistance to pre-emergent herbicides remains low

- In medium and high-rainfall areas, researchers and advisers encourage increased use of:

- double breaks (growing two broadleaf crops in successive years);

- double knocks in summer fallows;

- mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicides; and

- stacking all of the above tactics within each crop

- Continuous cereal cropping is selecting for increased dormancy and wider germination windows in annual ryegrass

- Crop competition and effective pre-emergent herbicide strategies can be used to reduce the impact of late-emerging annual ryegrass, but these are best used as part of an integrated weed management package

Herbicides are an easy way to manage weeds, but new research shows that relying on spraying alone is not sustainable.

The University of Adelaide’s Professor Chris Preston recently outlined worrying trends in annual ryegrass resistance to herbicides.

His findings were presented at the 2023 GRDC Updates across New South Wales and at the 2022 Crop Protection Forum held at Wagga Wagga late last year.

His preliminary analysis of the outcomes of a national weeds management survey showed annual ryegrass resistance to herbicides was increasing. However, he also presented evidence that growing canola followed by a pulse crop ahead of a cereal phase would result in cleaner crops.

Report card

In 2020-21, researchers, with GRDC investment, visited paddocks in all grain growing areas to collect the seeds of weeds that survived winter herbicide control in wheat.

More than 1300 annual ryegrass samples were collected. The seed from these escapes was then tested for resistance to a range of herbicides. To be deemed resistant, 20 per cent of plants grown from seed collected had to survive a spray with herbicide. This aligns with what a grower is likely to see in the paddock.

Unsurprisingly, Professor Preston said annual ryegrass was the most prolific weed across Australia, except in paddocks from northern NSW to south-eastern Queensland.

“In the past, post-emergent herbicides were the mainstay of annual ryegrass control,” he said. “But now, there is a high level of resistance to the Group 1 selective grass weed herbicide pinoxaden + cloquintocet-mexyl, sold as Axial® 100EC (Table 1).

“Accordingly, for most annual ryegrass populations, the Group 1 ‘fops’ and ‘dens’ are no longer effective.

Table 1: Percentage of annual ryegrass resistant to various post-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020-21 across Australia.

Location | Resistant samples(percentage) | |||||

Axial® 100EC | Clethodim | Hussar OD | Intervix | Glyphosate | Paraquat | |

National | 71 | 23 | 91 | 79 | 16 | 0 |

NSW | 73 | 17 | 86 | 67 | 23 | 0 |

Victoria | 73 | 10 | 95 | 86 | 22 | 0 |

Tasmania | 86 | 52 | 71 | 57 | 0 | 0 |

SA | 66 | 14 | 85 | 68 | 14 | 0 |

WA | 71 | 35 | 98 | 92 | 12 | 0 |

Source: Preston, C., et. al. (2023), ‘Optimising control of annual ryegrass’. Proceedings of the 2023 Wagga Wagga GRDC Grains Research Update.

“Clethodim (Select®) is also a Group 1 herbicide, but it behaves differently because it comes from the ‘dim’ family. Consequently, we often find that where Axial® does not work, we can still use clethodim.”

Nonetheless, he said clethodim resistance was becoming a bigger issue, even when weeds were sprayed at the ideal growth stage – when two to three leaves had developed – under ideal conditions using label rates.

“Often, clethodim is applied when annual ryegrass is large. But annual ryegrass with resistance to clethodim often survives at this growth stage.”

In terms of the Group 2 active ingredients, the survey demonstrated high levels of annual ryegrass resistance to the sulfonylureas, with resistance also flowing into the imidazolinones (IMIs), rendering formulations such as imazamox (Intervix®) ineffective.

GRDC grower relations manager Graeme Sandral added that there can be variability between paddocks on farms and in regions.

Glyphosate resistance

Concerningly, Dr Preston said annual ryegrass resistance to the Group 9 herbicide glyphosate was at an all-time high.

“In the past, annual ryegrass resistance to glyphosate was rare, but it is now increasingly common,” he said.

Fortunately, however, annual ryegrass did not show any resistance to the Group 22 active paraquat (which includes products such as Gramoxone®). “That does not mean weeds resistance to paraquat doesn’t exist,” Dr Preston said.

“We know we have some paraquat resistance in annual ryegrass, but it is localised and at low frequencies in the wider grain belt.”

Pre-emergent herbicides

Overall, he said the survey confirmed that effective annual ryegrass management now hinged largely on pre-emergent herbicides.

He said annual ryegrass had a much lower frequency of resistance to pre-emergence herbicides (Table 2).

Table 2: Annual ryegrass resistance to various pre-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020-21 across Australia.

Location | Resistant samples (percentage) | |||||

Trifluralin | Prosulfocarb + Metolachlor | Pyroxasulfone | Propyzamide | Cinmethylin | Bixlozone | |

National | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NSW | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Victoria | 21 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Tasmania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SA | 38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

WA | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Preston, C., et. al. (2023) ‘Optimising control of annual ryegrass’. Proceedings of the 2023 Wagga Wagga GRDC Grains Research Update.

“Trifluralin resistance is the worst in South Australia and Victoria,” he said. “We are seeing a little more resistance to Group 15 herbicides, particularly products like Avadex® and Boxer Gold®, which is not necessarily flowing into other Group 15 herbicides like Sakura®.”

Propyzamide, found in Rustler® for example, is still working on annual ryegrass, he said, which was interesting because it was in the same herbicide group as trifluralin.

“For newer products such as cinmethylin (Luximax®) and bixlozone (Overwatch®), we’re just not picking up resistance in our survey, which doesn’t mean annual ryegrass resistance to these products is not there.

“We know there is resistance to both herbicides in some annual ryegrass populations, but the frequency is still very rare.”

Control tactics

Dr Preston said that annual ryegrass was usually more difficult to control in areas where winter rainfall was high. This was because of extended plant emergence during the growing season.

“Surviving weeds can set a lot of seed, leading to rapid increases in population size,” he said.

Accordingly, trials in the high-rainfall zone of SA and Victoria had identified several key strategies for managing annual ryegrass, which included using:

- double knocks;

- double breaks;

- mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicides; and

- stacking tactics.

Double knocks are used where glyphosate is applied to control summer weeds, followed by an application of paraquat (second knock) to control any survivors. This provides much better weed control going into the growing season.

Double breaks involve growing two crops in a row where high levels of annual ryegrass control can be achieved. Examples include growing a pulse crop or vetch followed by canola, canola followed by oaten hay or oaten hay followed by faba beans. Well-managed double breaks have been sown to reduce the annual ryegrass seedbank to low levels.

Pre-emergent herbicide mixtures or sequences of pre-emergent herbicides extend the period of control of annual ryegrass and can help reduce the number of plants setting seed. This tactic is useful where there is extended emergence of annual ryegrass and the lack of effective in-crop herbicides means annual ryegrass could escape pre-emergent herbicide control, particularly when growing cereals.

Stacking tactics within a season helps keep annual ryegrass numbers low.

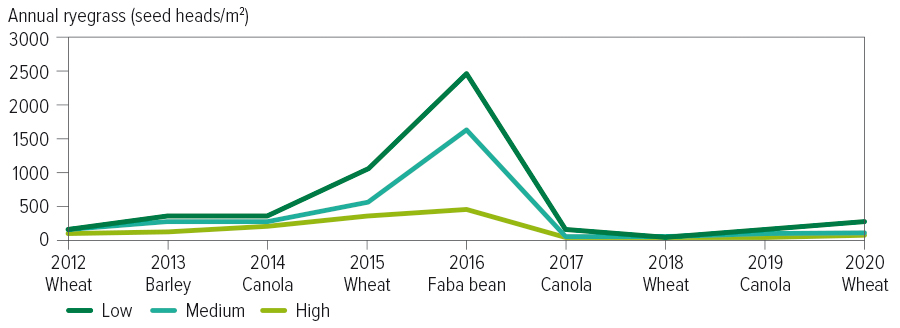

Professor Preston said a long-term trial at Lake Bolac in Victoria, from 2012–20 showed that a high-cost weed management strategy – which involved using two to four annual ryegrass control tactics per crop – for annual ryegrass management limited the increase in weed numbers for subsequent crops (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The mean effect of control strategy (low, medium and high cost) on annual ryegrass seed heads per square metre in a nine-year trial at Lake Bolac, Victoria.

Source: Chris Preston, The University of Adelaide.

“As the high-cost strategy was able to maintain the annual ryegrass population at a lower size, and reduce the impact on crop yield, it provided a cumulative $1613 per hectare gross margin advantage, compared with the low-cost strategy, over the nine years of the trial,” he said

“The trial also indicated the value of the double break at reducing ryegrass numbers.”

Professor Preston said harvest weed seed control (HWSC) was less effective in high-rainfall areas because crops were generally harvested later.

“Nonetheless, HWSC is still useful to reduce overall annual ryegrass numbers,” he said.

“In higher-yielding crops, use HWSC in a practical way rather than in a ‘perfect’ way.

“For example, cut crops low only through known patches of weeds such as around trees and along fence lines to speed up the harvest, while still using the tactic to reduce annual ryegrass numbers.”

Emergence pattern

Dr Preston said the adaptability of annual ryegrass was a major reason it was Australia’s most-important weed in grain cropping.

“In addition to the evolution of resistance to herbicides, annual ryegrass can also evolve other traits that allow it to avoid control tactics, such as increased seed dormancy,” he said.

“There is evidence that populations of annual ryegrass have changed their emergence pattern to have more of the population emerge later in the season. This allows some populations to avoid control by knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides.

“Our work has allowed us to discover that increased dormancy within annual ryegrass populations is heritable and, therefore can be selected by the farming system.

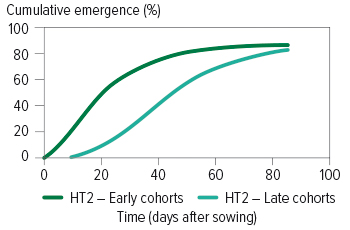

“In these studies, the early emerging and late-emerging proportions of populations were separated and crossed. The progeny of these two subpopulations had different emergence patterns (Figure 2), which equates to about a three-week difference in emergence between the two subpopulations.”

Figure 2: Annual ryegrass seed emergence.

Source: Chris Preston, The University of Adelaide.

Dr Preston said delayed emergence made annual ryegrass more difficult to control, particularly as reliance on knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides for annual ryegrass control was high.

“Management strategies will need to adapt,” he said. “Previously, we have shown that the combination of crop competition with effective pre-emergent herbicides is one tactic that can limit the impact of late-emerging annual ryegrass.

“Pre-emergent herbicide mixtures and sequences are also useful to provide longer control of emerging annual ryegrass.”

More information: Chris Preston, christopher.preston@adelaide.edu.au