Key strategies

Managing resistance in weeds, fungal pathogens and insect pests:

- Use a diverse range of non-chemical options, such as: harvest weed seed control (HWSC); selecting disease-resistant varieties; removing the green bridge; and conserving populations of beneficial insects

- When using agricultural chemicals, rotate between different Mode of Action (MoA) groups for each pest generation

- Use the recommended label rates when using agricultural chemicals.

When agricultural chemicals are used frequently there is an increased chance of resistance evolving.

Understanding the differences and similarities in the management of herbicide, fungicide and insecticide resistance will help growers to make better decisions.

The key strategies for managing resistance - and some of the common myths - are summarised below.

Differences

Resistance differs for different pest organisms and agricultural chemicals.

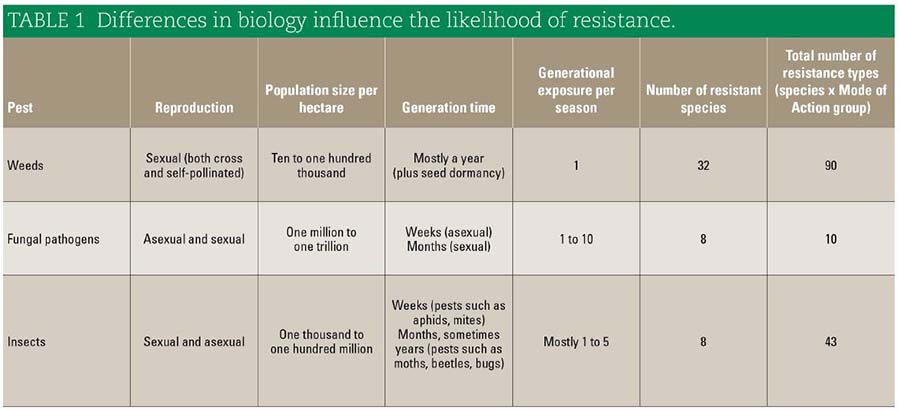

There are more opportunities for resistance to evolve when there is a large number of organisms in the field and resistance happens faster when there is a shorter generation time (as shown in Table 1).

Organisms that reproduce sexually typically have more chances of evolving resistance than those that reproduce asexually.

There are more chances for resistance to evolve if an organism reproduces many times in a season. Fungal pathogens reproduce rapidly as do many insects* (Table 1). With weeds there is generally only one generation per season though there may be several germinations.

Repeated application of agricultural chemicals from the same Mode of Action (MoA) group is a major reason for resistance evolution.

Challenging common myths

Relaxing the selection pressure does not always drive down resistance.

When growers stop using an agricultural chemical, the likelihood of resistance declining in a population varies enormously. The proportion of resistant individuals may decline quite quickly, but in other situations, resistance can remain just as common.

The outcome is largely dependent on the fitness penalty that occurs when an organism evolves resistance. If there is a fitness penalty, susceptible individuals will out-compete resistant individuals if the chemical is no longer used and there is no cross-resistance to other chemicals.

Mixtures** do not always limit the evolution of resistance.

The risk of resistance evolution may be reduced when more than one active ingredient in the mixture is effective against the pest. However, if one agricultural chemical in a mixture persists in the environment for a longer period of time (for instance when one insecticide decays slower than the other) this will select for resistance to that chemical.

Using rates at the lower end of the label range does not necessarily delay the evolution of resistance.

The full label rate is the most effective for managing weed and insect pests. Lower dosage rates are more likely to lead to survivors that may carry resistance. When spraying to control fungal pathogens use the label rate required to achieve adequate efficacy.

Rates at the lower end of the label rate may be appropriate when there is low disease pressure and the crop variety has some genetic disease resistance (a rating of moderately resistant or above).

More information: Dr Paul Umina, cesar, 0405464259, pumina@cesaraustralia.com

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Nick Poole, Dr Chris Preston and Dr Ken Young.

*The term insects throughout this Supplement refers to insects and other invertebrates (for example, mites). **Mixtures refers to on-farm tank mixes and/or commercial co-formulations containing at least two active ingredients.