Key points

- Scientists are refining the tactics needed to minimise feathertop Rhodes grass (FTR) establishment on grain farms

- Experiments are under way in sandy and heavy soils across southern NSW

- FTR can germinate as early as late August in southern NSW

- Carefully timed management that includes herbicide and non-herbicide tactics is needed to stop establishment and seed-set

With feathertop Rhodes grass (FTR) growing prolifically along the roads of much of Australia, NSW Department of Primary Industries principal research scientist Dr Hanwen Wu says research efforts are stepping up to help keep farms free of the invasive weed.

Despite being an established weed in northern cropping regions, Dr Wu is refining the tactics needed to control FTR in southern NSW farming systems. For example, he says FTR can start to germinate from late August or early September. FTR seeds will continue to germinate through spring, summer, and autumn, depending on rainfall.

When FTR germinates in winter crops, Dr Wu says seedling survival is likely to be inhibited by crop competition.

Research shows that when FTR seed germinates in fallowed paddocks during August and September, mature seed heads are produced about three months later, usually in November and December.

Dr Wu says that while crop competition is likely to inhibit FTR establishment, growth and development in winter crops, seed-set can occur in bare patches, along fence lines and in fallowed paddocks, from November to May, with additional germinations after successive rainfall.

“If FTR has previously set seed in fallows or along adjacent areas such as fence lines, a residual herbicide can be an effective tactic that needs to be applied before the first spring rain to inhibit seedling germination,” Dr Wu says.

“Most FTR infestations are isolated and patchy in southern NSW, which gives growers the opportunity to control them before the weed becomes widely established.

“FTR is more problematic on sandy, fallowed paddocks around Griffith, Hillston and Booligal in south-western NSW.

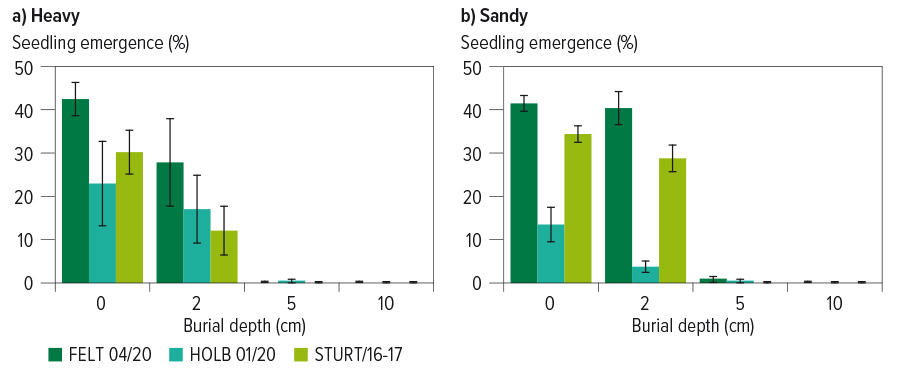

“Preliminary pot experiments have shown about 30 per cent of FTR seedlings emerged when seed was dropped onto sandy soils. By contrast, just 15 per cent of seeds dropped onto heavy soils produced seedlings.

“No FTR emerged when seed was buried deeper than five centimetres.” (See Figure 1.)

Inversion tillage is on the research agenda to determine whether this cultural weed management tactic helps prevent seedlings from emerging when buried deeper.

Figure 1: Emergence of feathertop Rhodes grass from different depths on heavy and sandy soils.

Source: Dr Hanwen Wu, NSW Department of Primary Industries, 2021

With GRDC investment and delivered through NSW DPI, experiments have been established at Goolgowi, Barellan, Lake Cargelligo and Wagga Wagga.

Central West Farming Systems and FarmLink Research are running demonstration sites at Condobolin and West Wyalong based on the project’s key findings.

A range of pre- and post-emergent herbicides, used on their own and in various mixtures have been assessed. The research team has also explored optimum herbicide timings.

Management tactics

Research shows a variety of weed management tactics are best employed to prevent FTR germination, establishment, and seed-set.

“If FTR is isolated and patchy, spot spraying, hand chipping and burning are effective options,” Dr Wu says.

“If you do not apply a residual herbicide before the first spring rain, be aware that FTR plants can emerge and grow larger than two to three tillers in about two to three weeks.

“Timing is critical when targeting emerged FTR and our research has confirmed the recommendation of applying a post-emergent herbicide when the weed is at early tillering stage is appropriate for central and southern NSW.

“Weeds grow quickly in the warmer months and the optimum herbicide application time can be easily missed.”

Dr Wu says weeds larger than two to three tillers are also less likely to be killed if post-emergent herbicides are applied in hot and dry conditions.

“If FTR is under severe moisture stress there’s no point applying a post-emergent herbicide because you will not kill the plants and it will be a waste of your money,” he says.

Herbicide experiments

“Some of the residual herbicide treatments we’ve tested have provided excellent FTR control for up to seven months,” Dr Wu says.

In post-emergent herbicide experiments, the research team found a double knock of one herbicide followed by another herbicide five to seven days later provided better FTR control than a single knock. A double-knock strategy also reduces the selection pressure on resistant individual weeds.

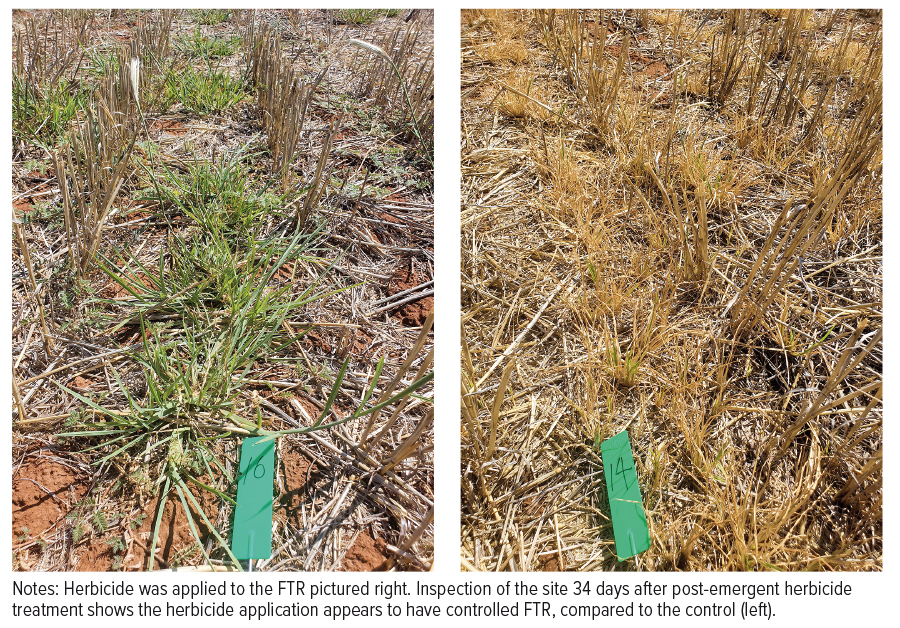

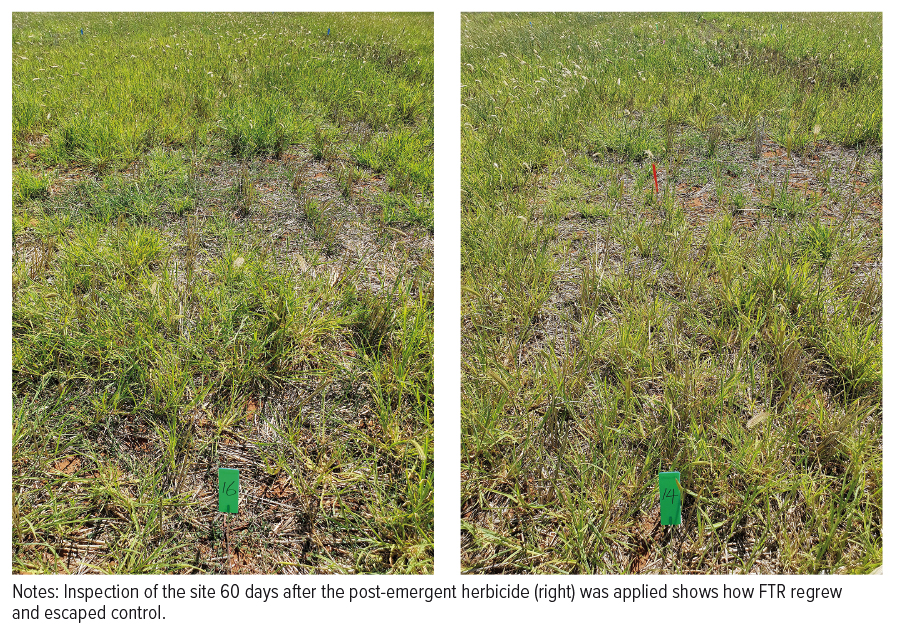

While post-emergent herbicides might initially appear successful 30 days after treatment, Dr Wu encourages careful and regular monitoring of the sprayed FTR (see Figures 2 and 3).

“Our research shows the importance of checking the success or failure of the application as FTR can escape control and regrow, particularly if plants were larger than the early tillering growth stage and were moisture stressed when sprayed,” he says.

Figure 2: Early herbicide timing assessed 34 days after treatment.

Source: Dr Hanwen Wu, NSW Department of Primary Industries, 2021.

Figure 3: Early herbicide timing assessed 60 days after treatment.

Source: Dr Hanwen Wu, NSW Department of Primary Industries, 2021

Grazing management

Another weed management tactic showing promise, for those in mixed farming systems, is the use of grazing to reduce seed-set (see Table 1).

Table 1: Preliminary results showing the impact of sheep grazing on feathertop Rhodes grass growth and reproductive features compared to two different graze and spray treatments.

Treatment | Number of tillers | Number of seed | Seeds per plant | ||||

No grazing | 25 | 16 | 1160 | ||||

Early grazing | 21 | 11 | 745 | ||||

Multiple grazing | 11 | 6 | 449 | ||||

Graze then spray | 7 | 1 | 155 | ||||

Spray then graze | 6 | 1 | 142 | ||||

LSD P = 0.05 | 4 | 5 | 120 |

Source: Dr Hanwen Wu, NSW Department of Primary Industries, 2021

“Sheep grazing is useful during the warmer months, especially when FTR is moisture stressed and likely to escape post-emergent herbicide control,” he says.

“If you have access to sheep, aim to graze FTR as often as possible, as our experiments show multiple grazing reduces seed-set by about 60 per cent. However, grazing on its own will not kill FTR so other control options are likely to be required.”

Dr Wu plans to repeat these experiments with the addition of slashing as a separate treatment, which is also showing promise as a tactic to delay and reduce seed-set.

Feed value

When it comes to the feed value of FTR, Dr Wu says crude protein and energy depend on the weeds’ growth stage (see Table 2).

“Feed value exceeded maintenance requirements at both the tillering and heading stage, but not at the maturity stage,” he says. “While readily eaten by sheep during early growth, FTR is avoided once it starts to mature”.

Table 2: Feathertop Rhodes grass feed value at different growth stages compared to vegetative annual ryegrass.

Growth stage | Crude protein | Metabolisable energy | |||

Seed maturity | 6.4 | 7.9 | |||

Heading | 12.7 | 10.1 | |||

Tillering | 17.0 | 10.7 | |||

Annual rye grass1 | 14 to 22 | 9.7 to 11.0 |

Notes: MJ = megajoules; DM = dry matter. 1. Annual rye grass measured at the vegetative stage. (Successful Silage Manual).

Source: Dr Hanwen Wu, NSW Department of Primary Industries, 2021

More information: Hanwen Wu, 0401 686 218, hanwen.wu@dpi.nsw.gov.au