Growers and agronomists may question whether dose rates have an impact on how likely resistance is to evolve, but resistance comes in many forms and trying to manipulate rates should not be seen as the core resistance-management strategy.

The reality is that using the most appropriate rate for effective control is the best strategy for managing resistance. Label rates have been developed to provide robust and reliable control of the target pest.

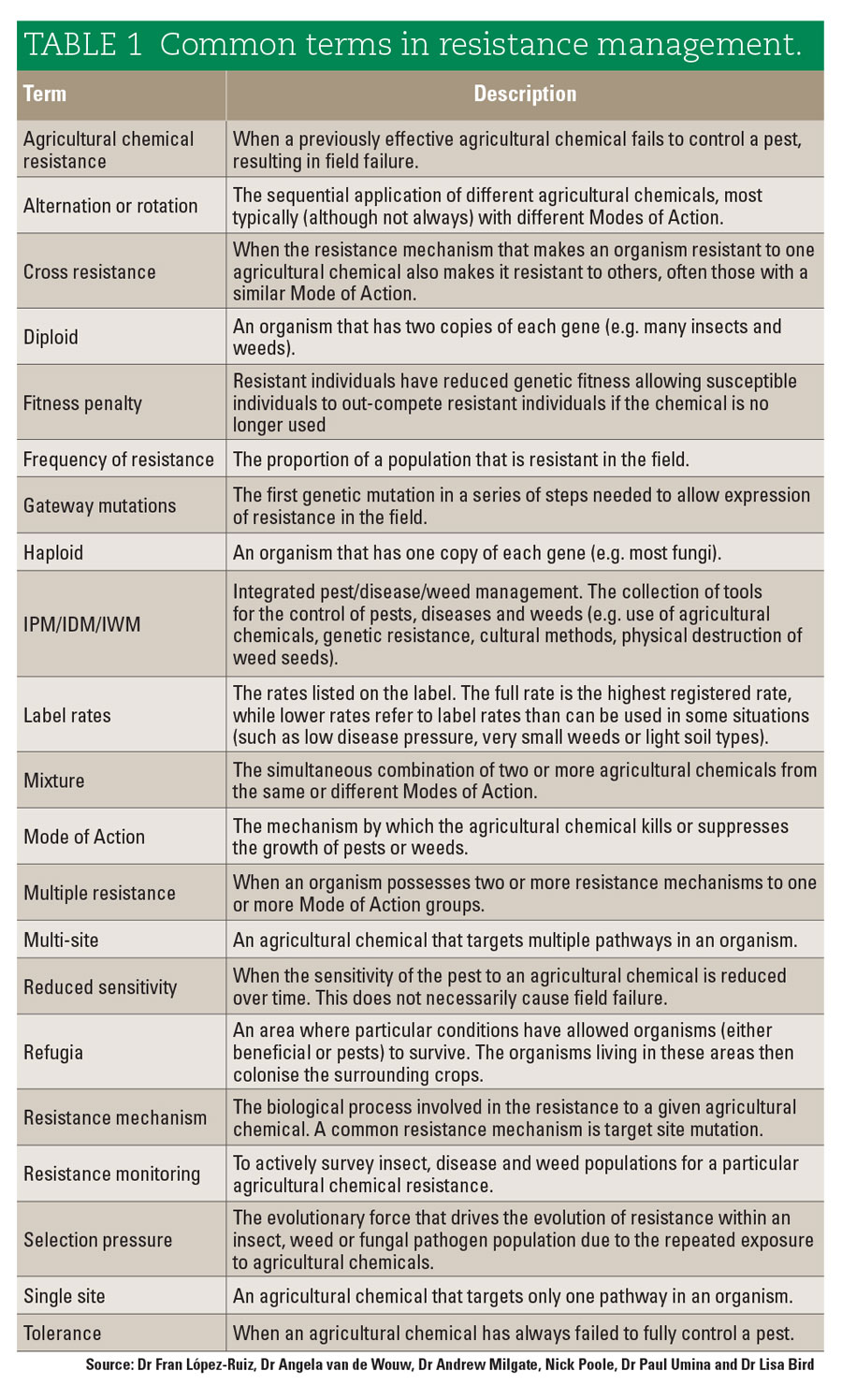

Table 1 Common terms in resistance management

Table 1 Common terms in resistance management

The influence of agricultural chemicals rates on resistance evolution is complicated by biological differences in the target organisms. As a result, there is no single answer regarding the influence of rate on resistance development. However, irrespective of whether it is weeds, pests or diseases, management decisions should be based on effective control of the target species. The application rate should not be seen as the core resistance-management consideration and should never prejudice effective control of the target organism.

Diseases

In many cases the full label rate is the most appropriate rate for control. However, for diseases, the lower rate from the label range of a fungicide can be used in conjunction with a crop variety that has a good disease-resistance rating, because disease pressure will be lower. There is evidence that using a higher rate than necessary increases the risk of resistance, as removing all of the sensitive individuals provides more opportunity for resistant individuals to dominate the population and hence be the dominant strain colonising the plant.

Weeds

For weeds, both low and high rates of agricultral chemical select for resistance. Less-effective rates of herbicides will result in more weeds surviving and bigger weed populations, so robuts rates should be used. High rates will typically select for resistance faster in self-pollinated weed species.

For outcrossing species, low rates may allow weak resistance mechanisms to be selected and accumulate within the population. When the mutations for resistance are partially recessive, lower doses will control the most sensitive part of the population, effectively leaving a higher proportion of individuals that carry resistance genes.

Insects

For insects, the situation is similarly complex. Insects that reproduce sexually often evolve resistance that involves many genes (poly-genic resistance). Of these genes, some are dominant or partially dominant and will confeer complete or partial resistance when inherited from one parent. Others are recessive and must be inherited from both parents in order to produce resistance. Then there are insects that reproduce asexually, which are more likely to develop major gene resistance and pass this on to all of their offspring. Dominance/recessiveness and single/multiple gene inheritance influence whether low insecticide rates will increase or decrease resistance issues.

For instance, low rates might increase resistance issues if recessive genes already present in a population and/or resistance is based on multiple genes. For these reasons, applying insecticides at the full label rate is recommonded when managing insect pests that have already evolved resistance. Irrespective of whether treating weeds, insects or diseases, management decisions on agricultral chemical rates should be based on effective control of the target species.

More information: Nick Poole, 03 5265 1290; Dr Paul Umina, 0405 464 259; Dr Chris Preston, 08 8313 7237.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Dr Fran Lopez-Ruiz and Professor Ary Hoffman.