Check list

- Ensure the highest standard of fumigation. Pressure test storages to ensure gas-tightness to meet recommended minimum concentrations and exposure periods. Invest in storage that meets the Australian Standard AS 2628, and seek advice from a local member of National Grain Storage Extension Team (phone 1800 WEEVIL).

- Limit the number of phosphine fumigations (two to three) for the same parcel of grain.

- Use alternatives such as sulfuryl fluoride only when strongly phosphine-resistant rusty grain beetles are detected. The existing label rates should control all other resistant pest species.

- Use grain protectants on freshly harvested grain. Treating old, infested grain with protectant chemicals will not control the infestation – only fumigation can disinfest it.

- Monitor insect infestations regularly. Send samples to a nominated regional laboratory for resistance testing and get further advice on pest and resistance management strategies.

- Adopt a proactive hygiene program. Clean up grain residues regularly in and around storages. Use diatomaceous earth in empty storage structures.

- Rotate grain treatments where possible. Use grain protectant products (such as chlorpyrifos-methyl and deltamethrin) and fumigants (such as phosphine and sulfuryl fluoride). This approach will break the resistance cycle for the respective treatment.

To maintain its position in highly competitive grain markets, Australia needs to adhere to a strict ‘nil tolerance’ protocol for live insects in its grain exports. To do this, the industry needs to minimise the development and spread of insecticide-resistant stored grain pest populations.

Preserving market competitiveness, and agricultural sustainability, can be achieved through best management practices. A critical part of this is a national insecticide resistance monitoring program.

National resistance monitoring

Since 1992, with GRDC investment, Australia has been the only country to have a national resistance monitoring program that systematically monitors and manages resistance to phosphine. Continuing this legacy, a GRDC-invested national program was initiated in 2019 to determine the frequency and strength of resistance to fumigants and grain protectants in major storage pests.

The national program runs collaboratively across the three GRDC regions (western, southern, northern) and is pivotal in limiting the frequency and spread of strong resistance to phosphine.

Led by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (QDAF), the three-year GRDC investment aims to survey 100 farms per year in each of these regions and undertake resistance diagnoses of several thousand pest populations over the life of the project. This will deliver a comprehensive assessment of resistance nationally, with implications for pest and resistance management options.

Laboratories will follow a statistically robust protocol to determine two levels of phosphine resistance (weak and strong). While monitoring weak resistance provides early indications towards future development of strong resistance, the results on strong resistance guide the implementation of appropriate management strategies to control those populations and contain their spread.

Dr Manoj Nayak (far right), GRDC national resistance monitoring project leader and Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries post-harvest grain protection team leader, and senior agronomist Philip Burrill (far left), discussing pest and resistance issues with growers in the Darling Downs region. Photo: DAF Queensland

The scope of the most recent investment has expanded to include monitoring of another fumigant, sulfuryl fluoride, and some grain protectants (for example, spinosad and chlorpyrifos-methyl). It is timely that resistance to sulfuryl fluoride be monitored due to its ongoing use by growers since its adoption in 2009 as a ‘phosphine-resistance breaker’. Grain protectants are used by about 20 per cent of growers in grain stored for a long period.

As part of the national program, a scoping study is being conducted in farm storages in the Townsville region to determine the pest spectrum and resistance gene frequencies. Townsville is traditionally a sugarcane region, but in recent years there has been a significant interest in cereals and pulses. In addition, Townsville is being positioned as a port of significance for containerised grain exports.

The aim is to explore the unknown factors related to phosphine resistance in this region bordering Charters Towers, Burdekin and Hinchinbrook, especially given the recent changes in cropping patterns and movement of grains across this and other regions, including central Queensland and the Darling Downs.

Findings

In the first year of the project (2019-20), despite COVID-19 restrictions, 158 insect populations were collected from 70 farms in the southern region, 385 populations from 63 farms in the north and 162 populations from 38 farms in the western region. While several of these populations are still being tested, diagnosis has been completed for 36 southern populations, 202 northern populations and 122 populations from the western region.

Overall, five (14 per cent) of the southern populations and 43 (21 per cent) of the northern populations were diagnosed as strongly phosphine resistant. Strong resistance was not detected in any of the 122 populations tested from the western region.

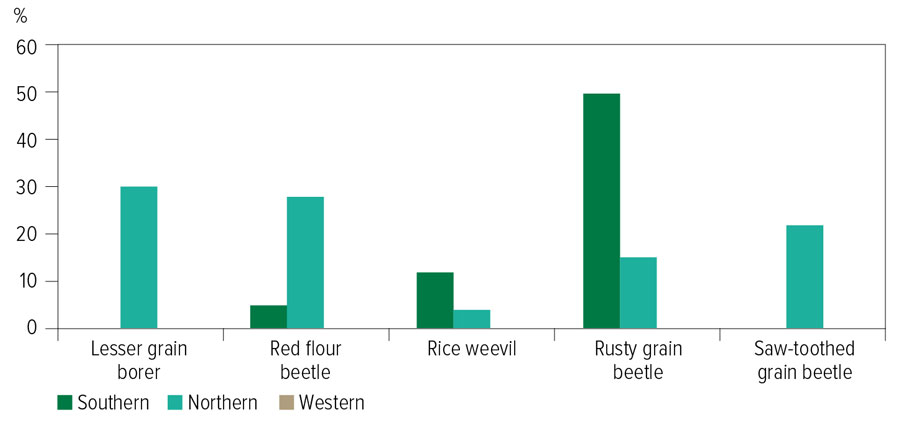

In summary, the northern region leads the strong resistance detections, with 30 per cent of the lesser grain borers, 28 per cent of the red flour beetles and 22 per cent of saw-toothed grain beetles tested revealing strong resistance profiles.

However, 50 per cent of the rusty grain beetles tested from the southern region were recorded as strongly resistant (Figure 1). All of the remaining populations from the northern and southern regions, and about half of those from the western region, were weakly resistant. Thus, the western region is the only region with populations susceptible to phosphine.

While resistance results are still pending for several populations, findings obtained so far show a trend in strong resistance frequency to be 14 per cent nationally. This elevation in frequency from the earlier five-year average of 10 per cent can be attributed to increased incidence of strong resistance in red flour beetles, lesser grain borers and rusty grain beetles, particularly in the northern and southern regions.

Recent visits to several farms have confirmed that residual pest populations do survive in empty storages during winter. If these pest populations are left untreated and/or storages not cleaned, they will infest new season grain when it is put into storage. Repeated fumigations to control these pests increases the likelihood of sublethal exposure and selection of resistance to phosphine.

There needs to be more awareness of how to best utilise lean periods such as winter to invest in hygiene in and around the storages.

Figure 1: Percentage of stored grain pest populations diagnosed with strong levels of phosphine resistance in farm storages across the three grain growing regions of Australia.

Source: QDAF

New regions not immune

Sampling of 14 storage sites (including farms, feedlots and grain processors) in the Townsville region, as part of the scoping study, revealed the incidence of at least one pest species population at each site. Further, all five major pest species were recorded in seven (50 per cent) of the storage sites inspected.

Molecular screening of lesser grain borers and red flour beetles revealed the presence of genetic variants linked to strong phosphine resistance in the populations of these species. Phosphine use to disinfest pests is limited in this region, so the prevalence of multiple resistant variants in pest populations suggests the possible movement of resistant insects via transportation of grain between Townsville, Central Queensland and the Darling Downs. This further highlights the importance of pest and resistance monitoring.

Emerging challenges for growers include the potential for more widespread occurrence of strongly resistant rusty grain beetles and rice weevils, particularly in the southern and northern regions.

The future direction in this research program includes development and inclusion of ‘quick tests’ for different stored grain pest species and undertaking molecular diagnostic monitoring of pest populations of other regions.

MythBusters

Stored grain pests are not around the storages when they are empty.

WRONG – Recent sampling in empty storages across many farms revealed several pest species in good numbers.

There is no need to clean storages if insects are not visible.

WRONG – A hygiene program should be deployed to kill the residual insect populations that are hiding and waiting to feast on the freshly harvested grain.

Grain protectants can be used to disinfest insect infestations.

WRONG – Grain protectants should only be used on freshly harvested grain. Infested grain should be fumigated.

Pickled seed grain provides protection from insect infestations.

WRONG – Many pickled seeds have fungicides that do not provide protection from insects.

I bought my silos and was told they are compliant to the Australian Standard (AS2628), so I don’t need to worry about pressure testing.

WRONG – Regular maintenance and pressure testing before each fumigation is required to ensure a silo can perform as an effective fumigation chamber.

More information: Dr Manoj Nayak, manoj.nayak@daf.qld.gov.au