The recent transformation in cropping practices from conventional to conservation agriculture (CA) has changed the population dynamics of mice. Paddocks now appear to provide a year-round safe environment for mice, which includes undisturbed nesting sites and shelter provided by standing stubble. Overall, the shift has created large areas where mouse populations can increase and potentially form plagues.

Obvious mouse runways connecting to mouse burrows within the cereal stubble. These burrows remained active after stubble rolling. Photo: Peter Brown, CSIRO

There is a long history of house mouse (Mus musculus) outbreaks in Australian grain growing regions where considerable damage occurs. However, current management regimes for mice are based on work undertaken before CA was commonly used. Some strategies even target mouse populations in refuge areas that were used by mice following paddock ploughing.

Given the multiple benefits of CA, it is unlikely growers will consider ploughing their fields to manage mice. Therefore, other modifications to CA practices could be required to minimise the benefit of this system to pest rodents.

Long-term studies have been undertaken of mice populations at Walpeup, Victoria, to lay the groundwork for these innovations. These studies have provided detailed knowledge of mouse ecology, demographic changes, spatial behaviour and disease ecology. The important drivers of mouse population dynamics are rainfall and habitat characteristics that affect the availability of food supply and nesting sites.

Trials are now underway with GRDC investment to inform best-practice mouse management strategies. A replicated before–after design was used to examine how cropping practices affect population densities of mice and their individual movements (using data from radio-tracked animals).

Mouse with a radio collar about to be released into a wheat paddock. Mice can be tracked with a special radio receiver and antenna to trace their movements at night and location of their burrows during the day. Photo: Wendy Ruscoe, CSIRO

Mouse with a radio collar about to be released into a wheat paddock. Mice can be tracked with a special radio receiver and antenna to trace their movements at night and location of their burrows during the day. Photo: Wendy Ruscoe, CSIRO

During the 2020-21 mouse plagues, various stubble management practices were compared, including stubble mulching, mechanical management (cabling, chain rolling or slashing) and burning. Mouse trapping and radio tracking were used to assess the effect of harvest and stubble management practices on the distribution and abundance of mice.

It was expected that the physical disturbance and/or reduction in habitat complexity associated with harvest and subsequent stubble management would lead to:

- reduced mouse abundance in paddocks following harvest;

- individual animals leaving the paddock to areas potentially more favourable; and

- reduced mouse abundance in paddocks following stubble management (flattening).

Field trials

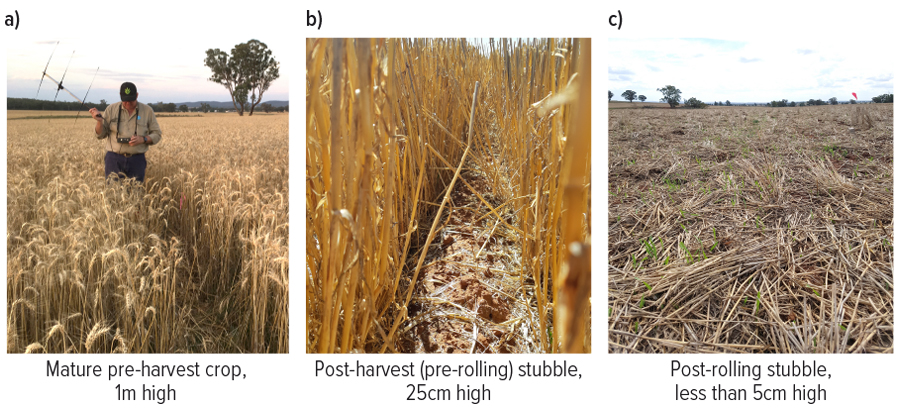

Paddocks were harvested by growers within a few days of each other in early December. Crops were less than one metre high, with near-total canopy cover. Following harvest, the remaining stubble was about 20 centimetres high, with about 30 per cent canopy cover remaining (Figure 1a).

Stubble management was undertaken using a prickle chain, disc chain or Ajust-A-Bar®. All three methods involved a tractor pulling a set of chains or discs across the ground, resulting in stubble being cut and laid across the ground to a height of less than 5cm (Figure 1b). There was a small amount of soil disturbance, but not enough to affect burrows.

Figure 1: Photos taken at various stages of crop height treatment on our study sites: a) pre-harvest, b) post-harvest and c) post-rolling. Source: CSIRO Health & Biosecurity, Canberra

Harvest impacts

Following harvest, more than 90 per cent of radio-collared mice that survived the harvest operations remained resident (using burrows) in the paddocks.

Two radio-collared mice were found dead in shallow burrows that were dug up under a harvester’s wheel tracks, and two animals could not be located on or near the trapping grids a week after harvest. Either they had left the area, or their transmitters had failed.

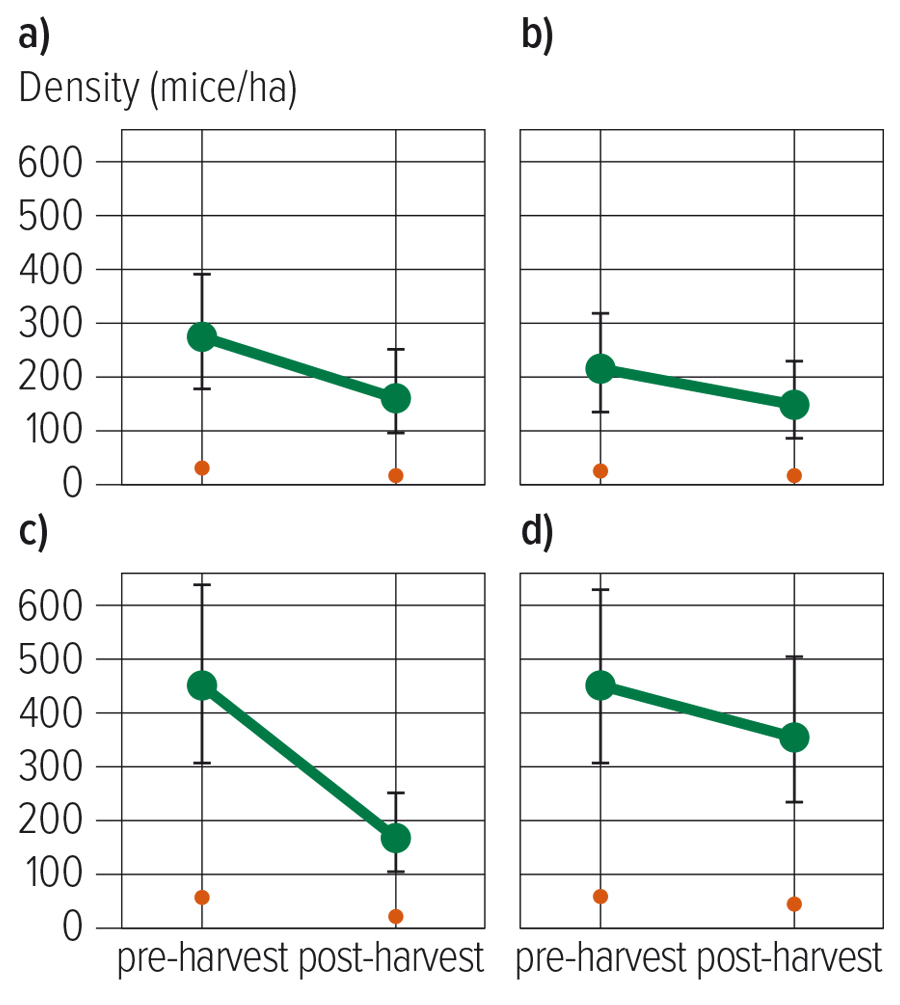

From our trapping studies, a 41 per cent reduction in the population size immediately following harvest was estimated (Figure 2), but this might have been due to a temporary reduction in the researcher’s ability to trap mice related to the disturbance by harvest machinery.

Figure 2: Change in mouse density (number of mice/ha) from pre-harvest to post-harvest on four farms. Source: CSIRO Health & Biosecurity, Canberra

Stubble rolling impacts

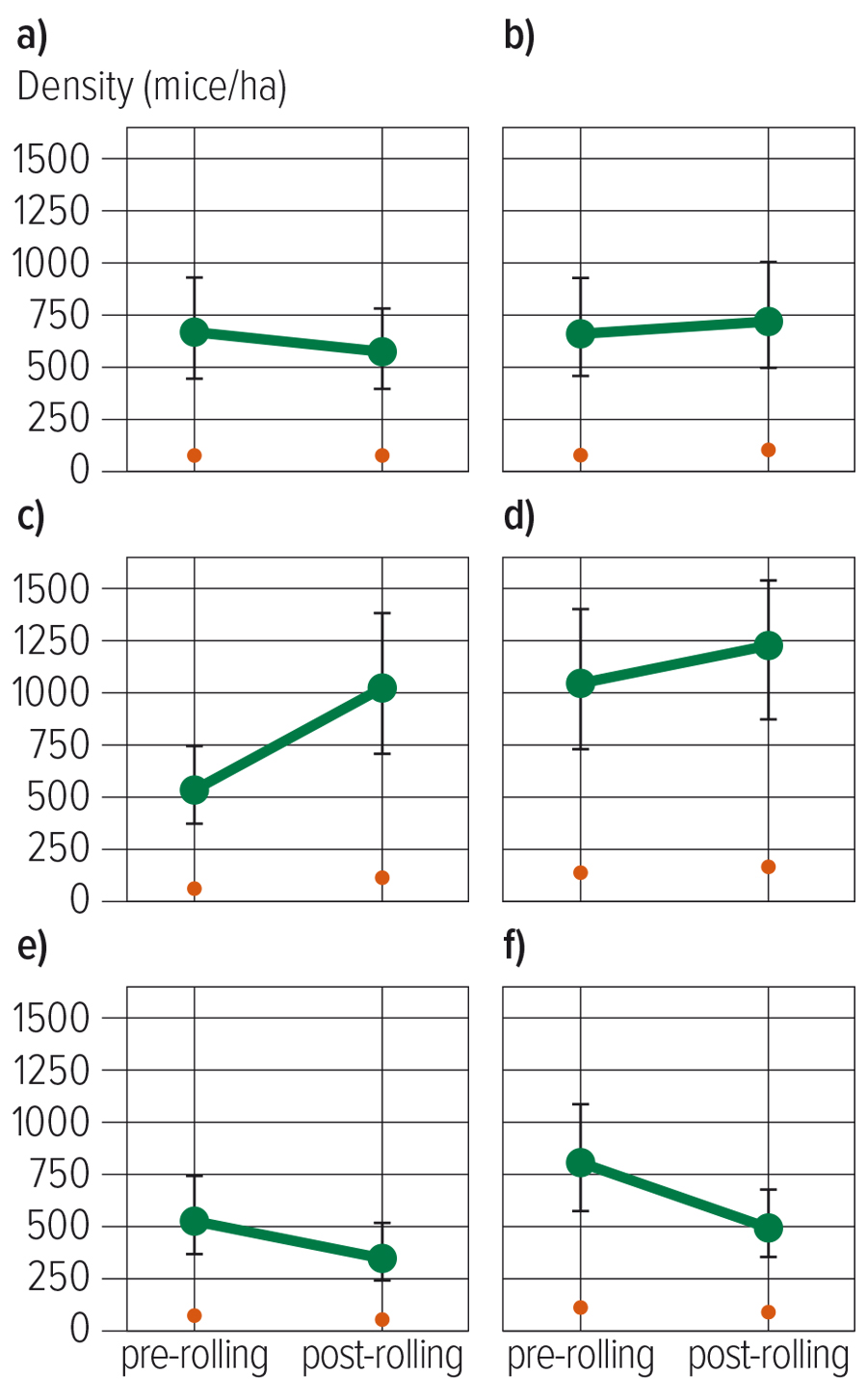

On average there was no real change in mouse density across the six sites as a result of stubble rolling (Figure 3). Population estimates peaked with a mean of 1200 mice per hectare, which is considered to be a plague.

Figure 3: Change in mouse density (number of mice/ha) from pre-rolling to post-rolling on six farms. Source: CSIRO Health & Biosecurity, Canberra

Even if the mechanical process of crop harvest kills some animals and/or induces other animals to leave the harvested area, the effect is temporary. It is also not sufficient to overcome the natural population increase at this time of year or prevent re-invasion by animals once the harvest disturbance has abated. Spilled grain remaining on the ground following harvest is a bountiful food supply for mice.

Previously, studies have shown that mice will select more complex habitats and vegetative cover to reduce predation risk. In contrast, it was found that stubble rolling itself did not cause a consistent emigration of mice (mouse numbers increased on three out of six sites). Mice were seen running both above and underneath the flattened stubble. The stubble rolling did not appear to have sufficiently altered the above-ground habitat (overall, it did not reduce plant biomass) and the burrows remained intact, making it an unsuccessful management practice.

Another option for managing mouse populations is to reduce food availability. This could be achieved by minimising the amount of grain left on the ground after harvest by improving harvesting machine efficiency or using ‘seed destructor’ technologies.

Other approaches to reduce the amount of spilt grain is to graze the stubble post-harvest, if livestock are part of the enterprise. A light tillage post-harvest could bury some remaining food sources, making it harder for mice to find, but is unlikely to provide additional benefit via burrow disturbance.

More information: Peter Brown, peter.brown@csiro.au; Wendy Ruscoe,wendy.ruscoe@csiro.au

Download the Mouse management guide.