Key points

- The new double-strength dose of zinc phosphide is improving baiting results

- Approved under permit earlier this year, the new dose comes about after progressive CSIRO research into baiting options

- However, management still requires an integrated approach and that includes reducing alternative food sources.

The new double-strength dose of zinc phosphide mouse bait is dramatically improving baiting outcomes for some growers.

Queensland agronomist John Fuelling says clients on the Darling Downs have had “far superior results” with the new strength bait. “There is no comparison to the single dose. Growers were baiting and then having to do it again 10 days later. They’d spend $20/hectare for no result. It was a real waste of time and effort.”

Approved earlier this year, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) emergency use permit increases the concentration of zinc phosphide active from 25 grams per kilogram of wheat grain to 50g/kg. Still applied at 1kg/ha, but with twice as much zinc phosphide on each grain, it increases the likelihood of a mouse consuming a lethal dose in a single feed. Manufacturers that are now making and distributing the 50g/kg product under permit include ACTA, Imtrade, PCT, Wilhelm Rural and 4Farmers.

B&W Rural’s Mick Brosnan, who is based at Mungindi on the Queensland/New South Wales border, says the benefits will be seen in rapidly reducing mice populations. “The bottom line is that with the new dose, we will only see a small percentage escape and that means the mice population won’t build up so quickly.”

His experience with his own a chickpea crop showed how quickly mice numbers can build. “I’d used some mouse chew cards and the numbers weren’t too high, so I planted and then went fishing for a week. When I came back, mice were destroying the stands so I aerial baited the next day. Even though it was the standard dose, it pulled them up straight away.”

He likens baiting to a cheap form of insurance. “The double dose will become the standard to get more mice with the first hit.”

Research

The double-strength dose of zinc phosphide came about from GRDC-supported CSIRO research and a permit application by Grain Producers Australia (GPA). The CSIRO research was the first laboratory-based wild house mouse bait efficacy study done in Australia since the chemical was registered for agricultural use about 20 years ago.

Lead researcher Steve Henry says the dosing work is a great example of the team’s progressive approach to managing the mice plague and a response to growers’ increasing dissatisfaction and frustration with baiting results.

It led the team to test for potentially tastier substrates and question whether there were populations of tolerant mice. “Zinc phosphide has been around for about 20 years, so we started thinking, have we been selecting mice to be tolerant to it?”

Using three groups of mice – one from an area where zinc phosphide is frequently spread, one where it has never been spread and one group of laboratory mice – that theory was tested.

However, there was no significant difference between any of the groups. “All were equally sensitive to zinc phosphide, but they were only half as sensitive to zinc phosphide as was reported in studies undertaken in the US in the 1980s.” This led to the further work and a field trial at Parkes, NSW, where the double dose stood out.

“The results show that with the standard 25g/kg dose there is a variable chance of killing mice. Sometimes you will get a really good result, sometimes not. However, with the 50g/kg dose you have a very high chance of killing a high proportion of the population. Greater than 75 per cent of the time, you will kill 80 to 90 per cent of the population. We are hopeful that it will make a difference to a range of bait applications.”

Alternative food

While the baiting results are promising, Mr Henry says the basics still need to be considered. “Baiting is just one component in management. I keep banging on about it, but it is really important to keep on top of alternative food sources.”

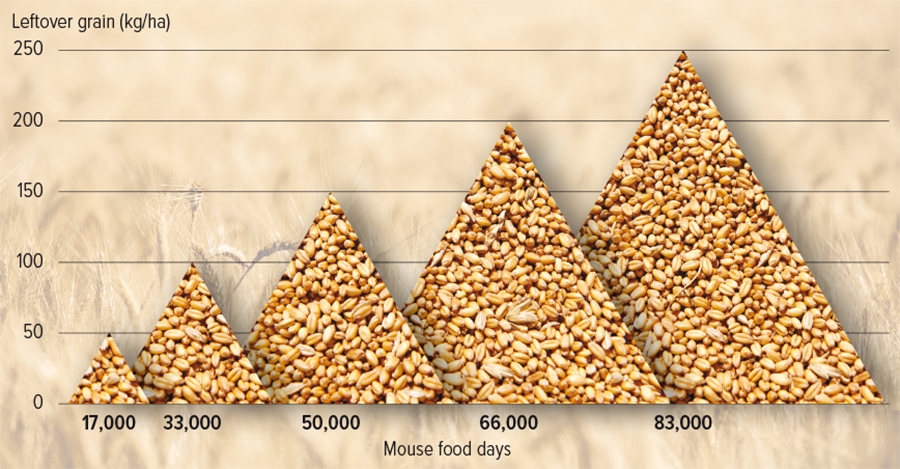

Figure 1: The importance of minimising harvest losses.

Source: Steve Henry, CSIRO

This includes undertaking a clean harvest. “Take the time to ensure the header is set up properly – not just at start of harvest, but also when changing crops and paddocks.

“Measure what’s coming out of the back of the machine. The less there is, the less food for mice and the more chance they will eat bait. And if you can avoid losing that grain, you are also putting more grain in the header bin.

“Also consider post-harvest stubble management like grazing and be proactive in spraying-out summer germinations. Any steps to reduce mouse food in the system helps to reduce mice numbers.”

GRDC pests manager Leigh Nelson agrees. “Mouse management requires an integrated approach and a key part of this is the reduction of alternative food sources, such as grain being left in the paddock post-harvest. This residual grain greatly reduces the probability of a mouse encountering and consuming a treated grain.”

Mr Henry says it is important to remember that mice eat about three grams of food per day. “Even if you think your paddocks are clean, remember only 150kg/ha of alternative food across your paddock equates to 50,000 mouse days of food.”

Likewise, knowing mice reproduction facts is important. “Mice breed at six weeks old and have litters of six to 10 pups about three weeks later. The kicker is that there is no break in pup production. When they give birth to their first litter, they can fall pregnant again within three days.”

This is important to factor in when monitoring paddocks and considering what actions to take. “You might assume that you don’t have a significant problem if there are 200 mice per hectare, but if 100 of those mice give birth to six offspring every three weeks, 200 mice become a big problem very quickly.”

Monitoring

Monitoring for mice in both established paddocks and in stubbles requires vigilance, Mr Henry says. “It’s important to get out of the ute, go for a walk and look for signs of activity. Not all paddocks will be the same and paddock histories of head loss or significant residual grain from a previous crop can indicate where significant populations might reside.”

There are two ways to check for mice – through chew cards and burrow counts. Detailed instructions for both can be found via GRDC's Mouse Management.

To monitor in a developing cereal crop, Mr Henry suggests using chew cards because it can be difficult to see the ground and count burrows.

In established crops, the key sign of damage is chewing at the node and heads in cereals and in canola, while legumes signs include chewed flowers and pods.

“As the crop develops, there is less and less food on the ground. So as the cereals start to form heads, mice start to chew into the node on the stem. At the milky dough stage, mice place great value in seeds and heads.”

Mr Henry says the key message is to bait as early as possible, before the crops are ripening and when there is no other food in the system. “Talk to your supplier to ensure you have what you need.”

When sowing into stubble, he suggests monitoring using both burrow counts and chew cards.

He says it is important to be vigilant about summer crops planted adjacent to winter stubbles. “These winter stubbles can be refuge habitats, and the potential for damage along the margins is quite high in freshly sown crops.

“It is not good enough to say: ‘the area I’m sowing into now is not a problem’, if just adjacent is a high mouse population ready to dine out of the freshly sown crop.”

When sowing summer crops, bait can be spread as the crop is sown. Soil is thrown when sowing with knives, helping bury residual food while placing the bait on top of the freshly turned soil. “This gives mice a good chance of finding the bait.”

Disc seeding is different, he says, but it will still create some soil disturbance, which changes the scent. “Mice like to investigate new things. Changed conditions in the paddock means that mice will investigate new areas and will hopefully encounter the bait.”

More information: GRDC's Mouse Management.