New research has turned the spotlight on the role root diseases play in the poor performance of pulse crops.

A mix of potential plant root pathogens have been detected nationally and plant pathologists are recommending greater surveillance. Growers and advisers are encouraged to be on the lookout for areas of poor growth in pulse crops and to dig up and examine the roots. The crops include lentils, faba beans and chickpeas.

Among the concerned pathologists are Blake Gontar of the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), the research division of the South Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA), and Dr Joshua Fanning of Agriculture Victoria. All are seeing signs of poor root health in many pulse crops.

They suspect the problem is a consequence of the shift from using pulses primarily as an occasional break crop between cereal phases to growing them more frequently given their comparative profitability.

“Since their introduction, grain yield, disease resistance and crop agronomy have improved to increase the profitability of pulses,” Dr Fanning says. “This has resulted in increased cropping frequency. Advisers and growers are very aware of the need to control leaf diseases; however, the risk posed by soil-borne diseases has been often misdiagnosed.”

Problems were apparent in 2017 when a SARDI pathology team responded to chickpea crop failures in South Australia’s south-east.

None of the usual culprits such as herbicide damage or foliar disease could account for the damage. In-depth DNA sequencing done by the SARDI Molecular Diagnostic Centre pointed to Phytophthora megasperma, a soil-borne pathogen not previously considered to affect pulse crops in southern Australia. This species is closely related to the devastating Phytophthora root rot disease in chickpeas in northern Australia.

Similar issues with poor root health were detected in Victoria by Dr Fanning during paddock surveys.

“Root health in pulse crops looked very poor in general, both in patches and across entire paddocks,” Dr Fanning says. “When we presented our findings, we discovered that pathologists across the country were making similar observations. Random and targeted paddock surveys confirm the problem is very common.”

With lentils earning as much as $700 a tonne, the possibility of crop failures due to the build-up of root pathogens is a major concern. So, too, is the possibility that sub-optimal root health is holding back the true yield potential of pulses. Root diseases may also be limiting pulse nodulation and nitrogen fixation, worth an estimated $220 million a year to the grains industry.

To better understand the situation, GRDC in 2019 invested in a national soil-borne disease project coordinated by Dr Grant Hollaway of Agriculture Victoria. A sub-component was led by Mr Gontar, who coordinated the project’s national survey and diagnostics component that further investigated poor-performing pulse crops.

The survey was undertaken in all states of mainland Australia over two growing seasons, with 880 samples from individual paddocks analysed by a mix of standard and new diagnostic methods. These methods included visual assessments and laboratory culturing. However, since not all pathogens are easy to isolate, Mr Gontar says that more advanced DNA sequencing technology was also used.

Mr Gontar says surprising discoveries have continued to pop up over the course of the three-year survey.

“Next-generation sequencing has allowed us to go beyond the easily cultured and known pathogens and see what else is present,” he says. “We have found the pathogen Aphanomyces euteiches is common in certain regions of SA, while multiple Sclerotinia species are present through NSW.”

The DNA of all potential pathogens in a sample were sequenced and advanced bioinformatics then allowed the huge amount of data to be processed in meaningful ways.

“That rapidly gave us a more-complete picture of the organisms present,” Mr Gontar says. “In some cases, once a new pathogen of interest had been identified, we could also develop rapid PCR (polymerase chain reaction) diagnostic tests.”

The survey identified some potential key pathogens that are a cause of immediate concern.

“In any one paddock we may have multiple potential pathogens,” Mr Gontar says. “The scale of the survey meant we got a good summary of which pathogens pose the greatest risk.”

The shortlist of key pathogens is:

- Phoma pinodella;

- Pythium species;

- Fusarium species;

- Phytophthora species;

- Aphanomyces euteiches; and

- Rhizoctonia solani.

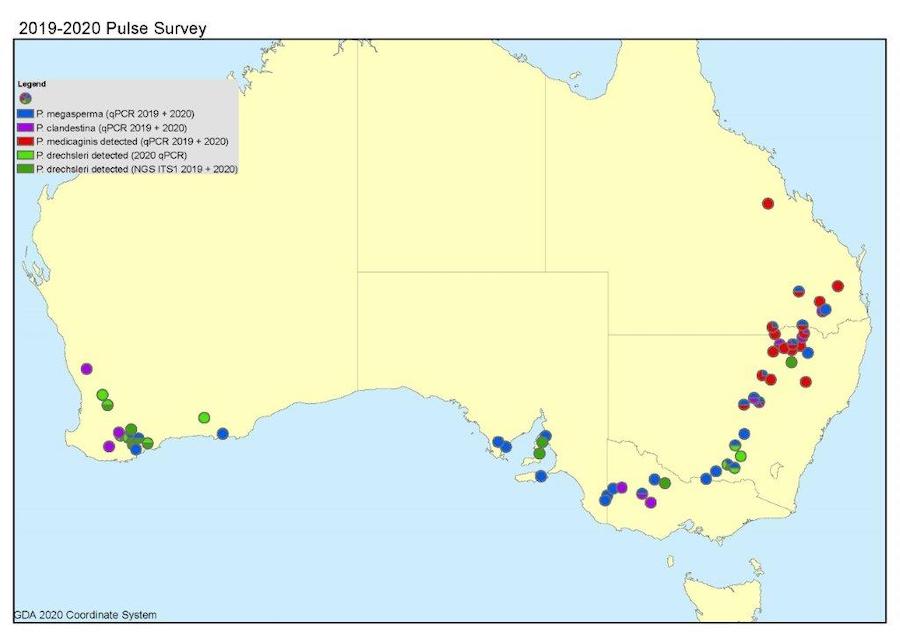

Map summarising results from the pulse root survey 2019-20.

Dr Fanning says the higher frequency of pulses in paddock rotations has caused disease outbreaks before, the most serious being the breakdown in chickpea resistance to foliar diseases in the late 1990s and again in 2015. While foliar diseases spread faster than root diseases, their impact is easy to identify in the paddock.

“Root diseases tend to spread more slowly but are more likely to be misdiagnosed until they cause major losses,” Dr Fanning says. “The survey has shown there are important pathogens now widespread and associated with substantial root disease. We need to determine the critical thresholds and seasonal conditions that expose pulse crops to unacceptable risk, and to develop management strategies to manage the risk.”

The research priorities include:

- quantify impacts on yields in different seasons;

- measure the effect on nodulation and nitrogen fixation;

- understand the interactions that trigger severe disease outbreaks; and

- determine how to control pathogen build-up and disease occurrence.

While this research is ongoing, Mr Gontar and Dr Fanning stress the importance of monitoring crop root health to make sure the build-up of root disease is detected before yields decline. “Targeting poor-performing areas is a good start,” Mr Gontar says. “If the roots are diseased, check the better crop areas – they may not be far behind.”

While research on root diseases of most pulses has been a low priority, new technologies have resulted in a rapid closure of the knowledge gap with cereals.

“Our understanding of what pathogens are present in pulse crops, and the types of root damage they cause, has developed quickly in just three years,” Mr Gontar says. “We now need to focus on prioritising the pathogens and understanding the conditions and magnitude of yield losses each are capable of, and then come up with economic management strategies.”

Watch your roots

Inspecting areas of poor vigour and plant death

Pulses have a reputation for being poorly adapted and harder to grow than cereals under Australian conditions, with lower tolerance for ‘tough going’. Previously, root diseases would go undiagnosed, but the latest data shows root disease should be considered where there is poor crop performance. Check root health in areas of poor crop growth, by carefully digging up some plants, washing the roots and inspecting for signs of disease and adequate nodulation. If you are concerned about what you see, contact your local department pathologist for advice.

Widespread and pathogenic

Pathogen: Phoma pinodella

Australian distribution: Widespread across all states

Pathogenic on: lentil, faba bean, vetch and lupin roots

Description: This species was known to form part of a complex of closely related pathogens that cause significant disease in field peas in the form of black spot of leaves and stem. It has now been found to cause root disease in all pulses, with modest yield losses likely across a lot of crops, but also with the potential to cause significant yield losses under severe conditions.

Chlorotic patches in lentil crop growing in Horsham, Victoria, associated with Didymella pinodella infection in roots. Photos: Agriculture Victoria.

Widespread with potential pathogenicity

Next-generation sequencing detected high levels of F. avenaceum in this faba bean sample from the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, in 2020. Photo: SARDI

Next-generation sequencing detected high levels of F. avenaceum in this faba bean sample from the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, in 2020. Photo: SARDI

Pathogen: Fusarium species

Australian distribution: Widespread across all states

Pathogenic on: lentils, chickpeas, field peas, faba beans, lupins

Description: Three species of particular interest include: F. avenaceum, F. acuminatum, F.redolens. All F. avenaceum isolates tested were highly pathogenic in pot experiments, and present in 20 per cent of samples. Some of the most-damaging Fusarium isolatesare subspecies of F. oxysporum; some isolates tested in the latest study were pathogenic and need to be identified further. Fusarium acuminatum/F. tricinctum was detected in more than 60 per cent of survey samples, and about half of the isolates tested were highly pathogenic. Fusarium redolens was detected in about 10 per cent of samples, and the two isolates tested were pathogenic.

Pathogen: Phytophthora species

Australian distribution: All states but especially in the northern region

Pathogenic on: chickpeas, lentils, faba beans and lupins

Description: P. megasperma and P. clandestina were detected in about 25 per cent of chickpea samples from the northern region that were also infected with P. medicaginis. The implications for projects breeding Phytophthora-resistant chickpea varieties should be investigated.

The survey also detected species closely related to P. drechsleri, which is extremely pathogenic on lupins. While not common, it is widespread, including in the south-east of WA, Kangaroo Island, northern Victoria and southern NSW. This species may have caused widespread failure of lupin crops in Victoria and southern NSW over 20 years ago that collapsed the industry.

Lentil crop affected by Phytophthora megasperma near Tumby Bay, South Australia, 2019. Photo: SARDI

Rare but very dangerous

Pathogen: Aphanomyces euteiches

Australian distribution: Kangaroo Island and south-eastern South Australia

Pathogenic on: lentils, faba beans and field peas

Description: This pathogen is known to cause severe root rot in lentils in Europe and North America. In this survey it was detected mainly on faba beans. Previous surveys also reported this species on faba beans in the northern region, and field peas in southern NSW and Tasmania.

More information: Overall project and South Australia: Blake Gontar, blake.gontar@sa.gov.au

Victoria: Joshua Fanning, joshua.fanning@agriculture.vic.gov.au

Southern NSW: Kurt Lindbeck, kurt.lindbeck@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Northern NSW: Sean Bithell, sean.bithell@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Queensland: Kirsty Owen, kirsty.owen@usq.edu.au

Western Australia: Carla Wilkinson, carla.wilkinson@dpird.wa.gov.au