Key points

- Blackleg resistance is influenced by specific farm practices, and regular monitoring of disease severity is essential to determine the risk of disease in your paddock

- While fungicide applied at 30 per cent bloom can reduce blackleg upper canopy infection, the yield benefit depends on many factors

- Changes in stubble management mean that spore release may be delayed to the second year after growing canola

Staying ahead of this evolving canola pathogen takes constant vigilance.

New research is developing blackleg management strategies based on a three-pronged approach of genetic resistance, cultural practices and fungicides.

With investment from GRDC, the University of Melbourne, Marcroft Grains Pathology and CSIRO are using molecular and field-based approaches to improve the management of blackleg – a stubble-borne disease that leads to seedling, crown canker and upper canopy infection.

Major gene resistance

Major gene resistance is an effective way to limit blackleg disease. This resistance is expressed throughout the life of the plant and, when effective, prevents the formation of leaf lesions, subsequent crown canker and upper canopy infection.

However, when varieties with the same major resistance genes are grown in multiple consecutive years, the blackleg fungus can evolve to overcome this form of genetic resistance. In just a few years, resistant individuals will dominate the population.

This research is monitoring the level of blackleg disease at 32 sites across canola growing regions in association with the National Variety Trials program. Varieties representing each resistance group are monitored to determine regional efficacy of the major resistance genes.

In 2020, monitoring indicated that Group H resistance was being overcome at Hamilton in western Victoria, and this was confirmed by molecular analysis of fungal isolates. The grower had sown Group H varieties for several years as a grain and graze option. Monitoring sites showed that the Group H resistance remained effective elsewhere.

While the monitoring site data indicates which resistance genes are generally effective in a region, it is recommended that growers and advisers monitor the level of disease in their own paddocks.

Upper canopy infection

Upper canopy infection refers to the development of blackleg lesions on the upper stem, branches, flowers and peduncles. Early sowing gets the crop established before winter but means crops are flowering in late July and throughout August, when conditions are ideal for blackleg spore release and they can land directly on the upper canopy.

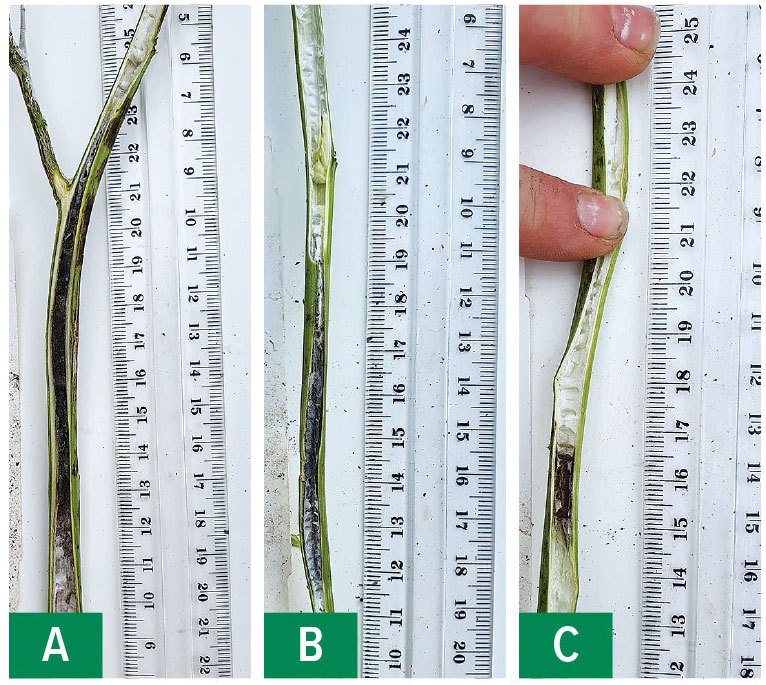

Figure 1: Examples of the level of stem infection of a (A) MS-S, (B) MR-MS and (C) an R variety.

Source: Dr Angela Van de Wouw

The 30 per cent bloom fungicide spray timing used to control Sclerotinia stem rot has also been shown to minimise the severity of upper canopy infection. However, while the use of fungicides reliably reduces the level of disease, the likely yield return varies dramatically.

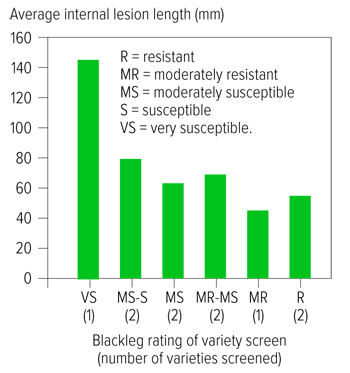

Figure 2: Preliminary data indicates that the average lesion length for upper canopy infection may be reduced by growing varieties with better resistance ratings.

Source: Dr Angela Van de Wouw

Preliminary data suggests that thermal time, water stress and genetic resistance may all contribute to the ability of a fungicide application to generate a yield response, and these are under further investigation.

When effective, major gene resistance can control upper canopy infection, but initial field observations suggested that all varieties may be equally susceptible without it. To test this, varieties with a range of resistance ratings were inoculated with individual isolates at the same growth stage in glasshouse experiments in Horsham and Canberra in 2020 to remove the variability observed under field conditions due to differing flowering times.

Preliminary results suggest that this initial observation is incorrect. Not all varieties that lack effective major gene resistance are susceptible and there may be some correlation between resistance to upper canopy infection and quantitative resistance – which is indicated by the variety disease rating (Figures 1 and 2).

These potential differences in genetic resistance may contribute to the variability in fungicide yield benefits being observed in trials and growers’ paddocks.

Changes in stubble management

The dramatic shift towards stubble retention over the past 20 years means that stubble now remains standing well into the following growing season, rather than being knocked down and starting to break down. Large visual differences in sexual fruiting bodies on the stubble in the field have been observed and this warranted further investigation (Figure 3).

Stubble was collected from the standing and laying down orientation over the two years following a canola crop and the spore release from the stubble was measured each month. In the year following the canola crop, significantly fewer spores were released from the standing canola stubble than the lying stubble.

When standing canola stubble was knocked down in the second year it produced a significantly higher number of spores than the stubble that had been lying down for two years. The total number of spores released was much higher in year two compared to year one. Unfortunately, this is often when canola is sown back into the paddock, putting the crop at much greater risk.

The impact of this change in spore release on disease severity is undergoing further investigation.

Figure 3: The number of fruiting bodies substantially increases when stubble is lying on the ground (top) compared with standing stubble (bottom).

Source: Dr Angela Van de Wouw

Blackleg incidence

Each year blackleg disease severity will vary between farms depending on rainfall, timing of rainfall, canola intensity in a region, variety resistance, fungicide use and sowing time. However, seasonal climate is also a major driver.

In New South Wales, blackleg levels were very low from 2017 to 2019 and did not cause significant issues. In 2020, blackleg returned and, while mainly well-managed, there was some damage in more susceptible varieties.

In Victoria and South Australia, blackleg has been much more variable between regions as a result of seasonal conditions. Generally, crown canker damage has been low due to early sowing and crops being established prior to cold winter conditions. Upper canopy infection has been very variable, with growers needing to make specific decisions on their individual crop at the 30 per cent bloom spray timing.

More information: Dr Angela van de Wouw, 0439 900 919, apvdw2@unimelb.edu.au; Blackleg Management Guide; BlacklegCM app