Snapshot

- Growers: Brendan and Melinda Weir; Kevin and Pat Weir

- Farm name: “Koorinya Farm”

- Location: Tenindewa, Western Australia

- Business enterprise: 100 per cent continuous cropping

- Property size: 3500 hectares arable

- Soil types: 80 per cent red loam, 20 per cent sand

- Soil pH: from 4.5 to 6.5

- Average annual rainfall: approximately 275 millimetres.

For 20 years, Tenindewa growers Brendan and Kevin Weir have painstakingly documented every weed control move they have made in what they call their “gravel pit” paddock.

The Weirs are one of 27 grain growing businesses in Western Australia’s northern agricultural region that have been part of a groundbreaking weed control research project with GRDC investment driven by WeedSmart’s Peter Newman.

By tracking weed control strategies in this focus paddock, combined with monitoring weed plant numbers over two decades, the Weirs have been part of an important pool of research information that will allow researchers and growers across Australia to implement more effective weed control management practices in the future.

As with the other 26 focus paddocks that have been part of the landmark project, the documented history of the “gravel pit” paddock makes for an interesting look back at how farming practices have changed.

“Before I went back through all the data and my documented management strategies, I thought we had not really changed our farming practices much over the past two decades, but now I can see we are doing things very differently,” Brendan says.

“This focus paddock is indicative of the changes we have made across the entire business.”

The Weirs farm at Tenindewa, near Mullewa in WA’s northern grain growing region, where annual rainfall is about 275 millimetres, with season breaks often in late May or even early June.

Brendan farms 3500 hectares with his wife Melinda and parents Kevin and Pat Weir. Two-thirds of their rotation is cereals and one-third is lupins and canola.

Weeds have been a major challenge for the business, as they are for many grain businesses in the region. Where once brome grass and ryegrass used to be the biggest headache, now wild radish has become the focus of the Weir’s weed management program.

Occasionally a paddock is left to fallow, but Brendan says this is only a strategy to control weeds, not to preserve moisture for the following year, given the sandy soil types across large percentages of the farm.

“I have found fallow works best only on the better soil types, and those are the soil types I will always put into crop,” he says.

“Fallow on the poorer soils – the sandier patches – does not do much for maintaining the moisture because of the soil type, so we would only use this as a way of controlling everything growing in that paddock in preparation for the next season.”

When this paddock survey project began in 2001, Brendan says his business had only trialled canola once as part of the rotation, his machinery did not have GPS guidance, there were no Clearfield® varieties on the market and trifluralin was not commonly used as a pre-emergent .

Sheep were also still a part of his mix.

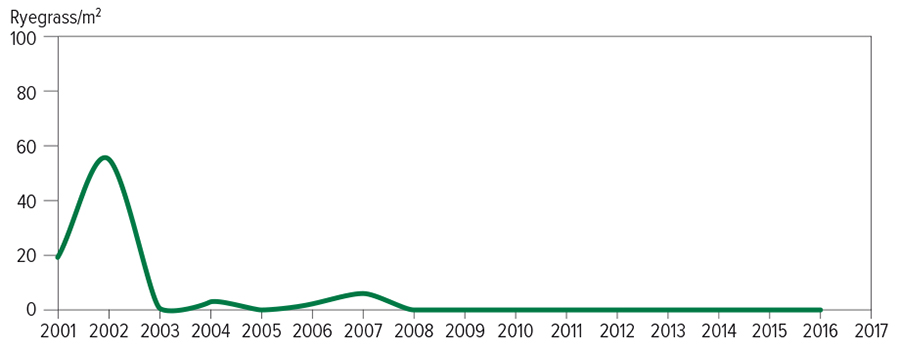

Spring ryegrass plant counts in the focus paddock in 2001 and in 2002 showed 20 and 55 plants per square metre respectively.

“Once we saw those numbers we became a lot more ruthless in making sure we got as many weeds out of the system as we could,” Brendan says.

Figure 1. The Weirs’ “gravel pit” paddock was one of 27 focus paddocks in the survey overseen by WeedSmart’s Peter Newman. Note: 2018 ryegrass blow out was not captured in this graph because the long term plant collection point was in a different area of the paddock.

“Thinking back, in the early 2000s we had just come off the back of a run of good years in the late 1990s, which allowed us to get good knockdowns before seeding, and we were not relying as heavily then on post-emergent applications.

“As a result, I think the weed seed numbers had been slowly building up over those years, and by 2001 and 2002 it became obvious we needed to do something more in terms of weed control.”

New chemistries

Brendan says the most significant turning point in the past two decades in regard to weed control was when the business introduced trifluralin as a blanket application into the seeding rotation.

“We first used trifluralin in a big way in 2002 and, by 2003, our ryegrass plant numbers dropped from 55 plants/m2 to almost zero – and have stayed low ever since,” he says.

“We made the decision to attack the weeds aggressively and it is a strategy that has worked well for us.”

With later breaks to the season, he says, there have been fewer opportunities in recent years to apply a glyphosate knockdown, meaning a greater reliance on in-season herbicide applications.

Brendan Weir says his business practices in regard to weed control have changed significantly over the last two decades. Photo: Evan Collis

Acknowledging the resistance issues that come with an over-reliance on one active chemistry, Brendan says the business now also rotates and mixes pre-emergent applications with both the Group K active pyroxasulfone, found in Sakura®, specifically for grass control; and the Group J and K product Boxer Gold®.

“The reliance on chemicals does concern me and, like most other growers in WA, we are seeing some resistance to Group C and Group I chemistries, so we know the answer is to keep mixing up our attack to keep on top of the weeds,” he says.

Wild radish is now arguably more of a threat to continuous cropping in the region than either brome grass or ryegrass and, in 2011, the Weirs introduced the post-emergent Group H and C herbicide (pyrasulfotole plus bromoxynil) found in the product Velocity® into their program.

“Interestingly, what we were finding when using Velocity® was the smaller radish plants that were part of a clump of plants were being protected and overshadowed by the larger radish plants. They were surviving, simply because they were not being directly contacted by the chemical,” Brendan says.

“So, again, we had to mix up our response to this to achieve a blanket control and we introduced Jaguar® (Group C and F) as an early post-emergent application, which so far appears to be working well.”

Harvest weed seed control

For their first foray into harvest weed seed control, the Weirs began narrow windrow burning their lupin paddocks, but with sheep still on the property until 2006, this was not as effective as it could have been in the early days.

“We sold all the sheep in 2007 after two of the worst droughts we had ever seen,” Brendan says.

“It had got to the point where we had been reducing numbers steadily and they were no longer a major part of the rotation, so it was not a major issue, but it allowed us to implement some more effective harvest weed seed control measures.”

Once the sheep were out of the system, the Weirs were able to narrow windrow burn most of their paddocks every year, taking a significant amount of weed seeds out of their system.

The Weirs continued this practice until 2018, when they believed they had weed seed numbers under control.

“Narrow windrow burning seems to be very effective, but it requires a huge labour unit investment prior to seeding to burn such large areas of the property.

“Interestingly, after pulling back on this strategy for a few years, we noticed the weeds were creeping back into the paddocks, and so now we use chaff lining to keep hitting the weed seeds after harvest, but without that huge labour component required to burn windrows in autumn.”

In the next few years, the Weirs will consider investing in an integrated mechanical seed mill to destroy the weed seeds at harvest time.

Rotations and varieties

Another significant change to the Weirs’ system over the past two decades has been the introduction of higher percentages of canola, including triazine-tolerant and genetically modified varieties, and a subsequent reduced reliance on a lupin/wheat rotation.

This has allowed the business to get a jump on wild radish, which was proving difficult with lupins in every paddock every two years. Clearfield® wheat and canola varieties also allow the business to have greater brome grass control.

“We are using every tool at our disposal to aggressively attack the weeds,” Brendan says.

The blow-out

However, it has not been all smooth sailing – with a wind erosion event creating havoc in 2018, destroying large areas of a sown canola crop in the focus “gravel pit” paddock.

With parcels of the more sandy soils within this paddock being completely exposed after the wind storm, Brendan made the tough decision to turn off the sprayer in these areas to ensure some ground cover over the paddock.

“As you would expect, we had a blow-out of both grasses and radish in these areas, and we had no canola yield whatsoever,” he says.

“To deal with this, we harvested those parts of the paddocks and burnt everything we took off these areas in the hope that we would capture as many of the weed seeds as possible.

“While those particular areas are not back to zero plant numbers yet, it did prove to be a good strategy and I am confident, given what we have achieved in the past, we will have it under control in the next year or so.”

This example illustrates that in just one year – and just one event – weeds can get the jump on even the best weed control strategy.

The survey

For WeedSmart’s Peter Newman, who has been overseeing the study since its inception in 2001 with assistance from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), the evolution of farming practices has been a clear theme among all the growers involved.

“When we started this project in 2001, only 50 per cent of paddocks had a pre-emergent grass spray, but within 10 years everyone involved was using a pre-emergent grass spray in every paddock, every year,” Mr Newman says.

“We have also seen a big reduction in reliance on the lupin/wheat rotation and, now with the introduction of canola into the system, some growers are only needing to rely on lupins once every six years, which has afforded them many more weed control options.”

WeedSmart's Peter Newman has been overseeing the paddock survey since its inception in 2021. Photo: Evan Collis

Mr Newman says the survey has highlighted the need for growers to take a long-term systems approach to weed management, rather than a reactive, single-year management style.

“We are now being more proactive and taking this longer-term view of the impact of weeds on business profitability, which has been a positive change in our management style,” he says.

“These growers are no longer thinking in one-year bursts but are acknowledging that sometimes you have to take a once-off hit in a certain season to see longer-term results.”

He says the willingness of growers to share management strategies and data with their peers – and with the broader industry – has been the real value of the project.

At the end of the 1990s, he says, growers in the region had lost confidence in their ability to have a future in continuous cropping programs.

“I remember sitting among these growers and discussing the very real possibility of having to return large areas of this country back to sheep, because we thought there may no longer be a future in continuous cropping simply of weed numbers.”

20 years of smart and aggressive weed management strategies, using multiple modes of action pre and post-seeding, plus the addition of harvest weed seed control measures, have given the growers the confidence to continuing cropping.

These growers are no longer thinking in one-year bursts but are acknowledging that sometimes you have to take a once-off hit in a certain season to see longer-term results.

He says innovative growers in this part of the country have been first adopters of various new technologies and strategies to get on top of weed problems.

As a result, growers have turned almost-uncroppable paddocks into clean, productive and very profitable parcels of land.

Mr Newman says growers have acknowledged the value in mixing up management strategies as a way to keep one step ahead of weeds every year.

“To me, this complete change in confidence levels, particularly among those growers involved in the survey, is a testament to the real value of this project,” he says.

“You can talk about how much money you can make by investing in diverse weed management, but the ultimate measure of the success of this program is that, very simply, these growers can keep cropping for the long term.

“The weeds are no longer calling the shots – the growers are back in control.”