Key points

- Nitrogen – as nitrate – is mobile but relies on soil water to move it through the profile

- Movement is slower than expected – often only to half or one-third of the depth of soil water movement

- This means nitrate can remain in the soil longer than expected and be a long-term benefit

- Increased nitrogen uptake efficiency is generally measured from residual nitrogen rather than from fertiliser nitrogen applied close to planting.

Nitrogen tends to stay in the farming system for longer than previously thought because its movement through northern soils – which typically have higher clay levels – is slower than expected, trials show.

This means that a longer-term management approach that aims to maintain soil nitrogen levels could be more beneficial than a shorter-term, reactive one.

Ongoing research by the Northern Grower Alliance (NGA) has found that nitrogen’s slow movement benefits crops, potentially for years after application. This opens the way for a steadier, longer-term approach to nitrogen applications, rather than an annual reactive approach.

NGA chief executive officer Richard Daniel says the organisation has been involved in GRDC-supported nitrogen management trials in wheat since 2012. These trials were focused on improving the efficiency and economics of nitrogen nutrition – a major production cost. Early work considered the economics and fit of late application, followed by a focus on refining application methods and timing.

Mr Daniel says the trials were only expected to last for one crop. However, soil testing at harvest showed large quantities of unused nitrate nitrogen. A decision was taken to monitor the residual impact of this nitrogen on following crops, as well as the longer-term soil movement and fate.

The research has generated a large body of regional data on uptake efficiency and soil movement.

“This has given us the chance to reflect on system implications and challenges and whether we really have got the system right." Richard Daniel, NGA CEO

Longer-term benefits

Mr Daniel says nitrogen has often been considered a “use it or lose it” nutrient. “Yet, what so much of this work has reinforced is that in our soil types and environment, if we don’t use all the applied nitrogen in year one, the majority of the excess is still there and available for crops in the following seasons.

“Once nitrogen is in the soil, the main pathways for loss are via leaching or denitrification from waterlogging events. Leaching is a major risk in sandy situations, but this work reinforces it is a low risk in higher clay content soils.

“Denitrification is the bigger concern. But this can be reduced by avoiding situations where you have high concentrations of nitrate nitrogen in the surface soil layers on already wet profiles.

“A key message from these studies is that, although a single nitrogen application is certainly going to benefit the next crop, it is also providing residual benefits to bolster the soil fertility for following crops.”

This has management implications, he says. “For so long, nitrogen application has been a bit of a knee-jerk reaction. That is, if you have low protein that year, put in more for the next crop. But in reality, that nitrogen is continually moving and cycling through the soil.”

Instead, the research suggests that applying a regular, adequate level of nitrogen suitable for the individual rotation may be a better approach. “Perhaps after a big yielding year (you should) lift that amount, but otherwise try to maintain a more regular application. It will keep the system robust in terms of fertility because there are much longer benefits from applying nitrogen than we generally expect.”

The speed of nitrogen movement was investigated in NGA trials, with surprising results. Over a three-year period (2015–17), nitrogen was applied into a dry soil profile during fallow at 10 sites. The hypothesis was that the nitrogen would move further with fallow rain events and be deeper and more uniformly distributed by planting and more beneficial than nitrogen applied close to planting.

“However, the results showed that even in a dry soil profile with about 150 to 200 millimetres of fallow rain, nitrogen movement in these predominantly vertosol soil type trials was slower and shallower than expected.

“The majority of nitrogen applied in fallow, either surface-spread or incorporated to depths of three to five centimetres, was still in the zero to 15cm soil segment at planting.”

The relatively shallow and slow movement of applied nitrogen is also likely to be a major cause for inefficient nitrogen recovery in the year applied. Mean levels of 15 to 20 per cent applied nitrogen were recovered in grain at common commercial rates of 50 to 100 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare in the year applied. It was not that large amounts of nitrogen had been lost, rather that the nitrogen was in a location that was not very effective for crop uptake during that season.

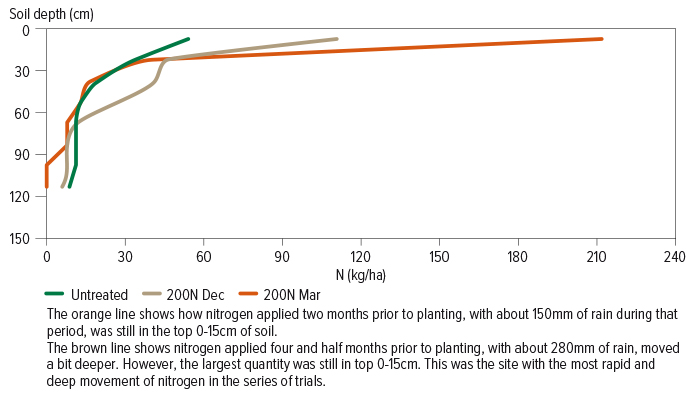

Figure 1: Soil distribution of nitrogen at Billa Billa, in Queensland’s Goondiwindi region, at planting (May 2017) following urea application in December 2016 or March 2017.

Source: GRDC

Source: GRDC

Industry challenges

Looking to the future, Mr Daniel says there are challenges. “We need to ensure that nitrogen levels in the soil do not continue to decline. This is because the required levels of nitrogen fertiliser in the year of cropping would rapidly become uneconomic and impractical and impact heavily on crop productivity.”

He also suggests that methods need to be identified to get nitrogen fertiliser deeper in the profile – more quickly – to improve availability and efficiency, while unaccounted losses from nitrogen fertiliser application need to be identified and if possible managed.

“The results indicate we still have much to learn, or at least to refine, with the management of our most important and best understood nutrient for cereal production.”

More information: Richard Daniel, 07 4639 5344, richard.daniel@nga.org.au