Key points

- Most pulses are highly vulnerable to soil acidity, which is on the increase across South Australia

- Early liming of acid soils is important to prevent the development of subsurface acidity as pulses seem to be sensitive to acid bands in the soil

South Australia’s soils were largely neutral to alkaline when first cleared, but many decades of productive cropping have led to a rise in soil acidity. Lentils, vetch and – to a lesser extent – faba beans are highly sensitive indicator crops for acidity.

Acidity management provides lasting benefits, and the cost can be quickly recouped from these crops.

Areas affected are expanding, particularly where poorly buffered soils are being used for intensive cropping rotations with high yields and high nitrogen fertiliser inputs.

Under no-till systems, soil acidity appears in a patchy distribution, across paddocks and at depth. In some soil types, pH stratified profiles are common, sometimes after liming, often with an acidic layer around seven to 15 centimetres deep.

Led by the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), the GRDC-invested research aims to generate new information regarding lime movement and its effectiveness when applied to different soils and environments in modern farming systems. The Murraylands and Riverland Landscape Board, Hills and Fleurieu Landscape Board, the University of Adelaide, Trengove Consulting and Penrice quarries are partners in the three-year study.

Liming trials

Eleven trial sites have been established across SA since the project began in 2019, including several sites where soil acidity is an emerging issue. Sites include a range of soil types, rainfall zones and liming histories, including two that were limed previously.

Elemental sulfur treatments were applied to most sites to accelerate acidification and simulate future productivity losses if treatment was not undertaken.

The trials showed large improvements in an acid-sensitive legume at three of the four sites where legumes were grown in the rotation as a grain crop or for feed.

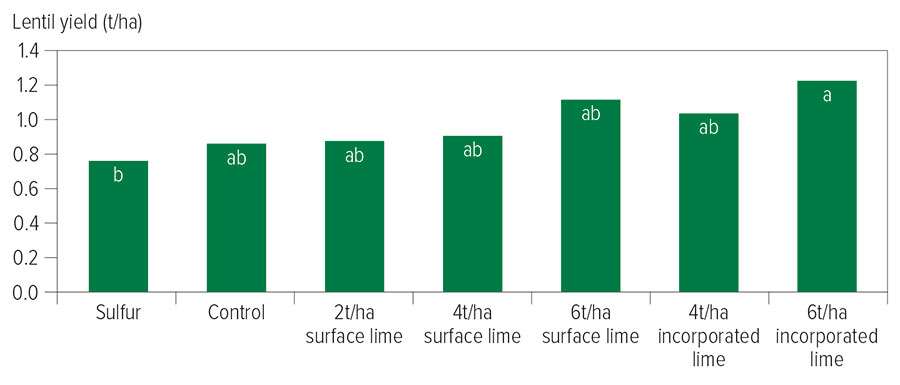

At Sandilands, a loamy sand with ironstone gravel over red clay (pHca 4.4/4.1/4.5/5.1 at 5cm increments), lime treatments were applied in 2019. This resulted in up to 60 per cent increase in lentil dry matter in 2020 and up to 30 per cent increase in grain yield (Figure 1). Lime improved yield the most when applied at the highest rate (six tonnes per hectare) and incorporated.

Figure 1: Lentil yield at Sandilands, South Australia, in 2020 with different lime rates and surface application or incorporated by tillage in 2019. Significant difference indicated by the letters, a/b (p<0.05).

Source: Andrew Harding.

At Spalding – a light sandy clay loam sodic red-brown earth (pHca 4.4/4.4) – lime treatments applied in 2020 doubled the biomass of vetch grown in 2021.

Symptoms of acidity observed on control plots included stunted yellow vetch plants with poor nodulation. End-of-season sampling showed large increases in legume rhizobia persistence where lime had been applied and pH increased.

At a number of trial sites, lime increased the availability and uptake of molybdenum, which is important for nodulation, and decreased levels of plant manganese, which can accumulate in toxic levels when pulses are grown under acidic conditions.

At Koonunga, deep incorporation or subsurface application of lime provided the best responses on a pH stratified profile in faba beans.

Early amelioration of acid soils is important to prevent the development of subsurface acidity, as pulses seem to be highly sensitive to acid bands deep in the soil. Targeting a pHca of 5.5 or greater in the top 10cm when liming often avoids issues with subsurface acidification.

On sandy soils, treatments such as tillage or clay addition can help reduce soil acidity. Modest improvements in pH have also been observed where composted manures or gypsum have been applied at some sites.

The research is working to gain a better understanding of soil variation, pH stratification, liming strategies and lime movement to improve the management of soil acidity.

More information: Brian Hughes, 0429 691 468, brian.hughes@sa.gov.au, acidsoilssa.com.au