Break crops were introduced to many Australian farming properties to manage pests, weeds and diseases in continuous cereal rotations. However, with continual changes in status of herbicide resistance weeds and soil-borne pathogens, a single break crop is becoming less effective in the wheatbelt region of Western Australia.

A closer look is being taken at the potential of stacked rotations (or double breaks) to reduce the impact of these biological constraints, in combination with an evaluation of the profitability of such breaks using high-value legumes. Results are showing that the performance of double-break crops is contingent on the species of break crop, nature of the biological constraint, season and soil type, but can be successful where correctly tailored.

With GRDC investment, the West Midlands Group and Corrigin Farm Improvement Group have taken two approaches to investigate the potential of double break crops for medium rainfall zones of WA, with a detailed replicated trial at Merredin and demonstration sites at Bencubbin, Calingiri and Corrigin.

“Using a double-break crop sequence can pair the best of two crops to address this issue,” says Dr Nathan Craig, executive officer of West Midlands Group.

“For example, this might mean using a Roundup Ready canola for weed control in the first year then a high-value legume to increase the profitability of that two-year sequence. Alternatively, it could involve using a clean chemical fallow in the first year to retain soil moisture and ensure a clean paddock, to optimise profitability of a high-value legume in the second year,” he says.

“It requires a change in mindset to view the economic and systems rewards over a longer timeframe, but it can be risky and dependent on season and soil type.”

Detailed field trial

A replicated field site, 12 kilometres north of Merredin in the eastern wheatbelt of WA, was used for detailed investigation. This site had a high background population of annual ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) and was previously cropped to wheat in 2015. It was a sandy duplex soil with a soil pH (CaCl) of 4.8 from 0 to 10 centimetres from the soil surface and 4.6 in the 10 to 20 centimetres of soil depth.

Twelve double-break rotations (described in Table 1) were established in 2016 at the site in a randomised block design experiment with four replicates. There was a particular interest in examining acid-tolerant break crops for this particular site. In this respect subclover, balansa clover, lupins, oats and field peas were included. This site was sown using a knifepoint seeder with press wheels on 24.7cm spacings and mechanically harvested with a plot harvester.

Growing season rainfall was below the site average of 245 millimetres in 2017 (195mm), and closer to average for the 2016 (253mm) and 2018 seasons (212mm). Above-average summer rainfall occurred in 2016 and 2017 and severe frosts were recorded in 2016 that affected all sites. Break crop growth and grain yield in this study were reduced by frost in 2016 and dry growing season conditions in 2017. Wheat growth and yield were not affected by severe seasonal conditions in 2018.

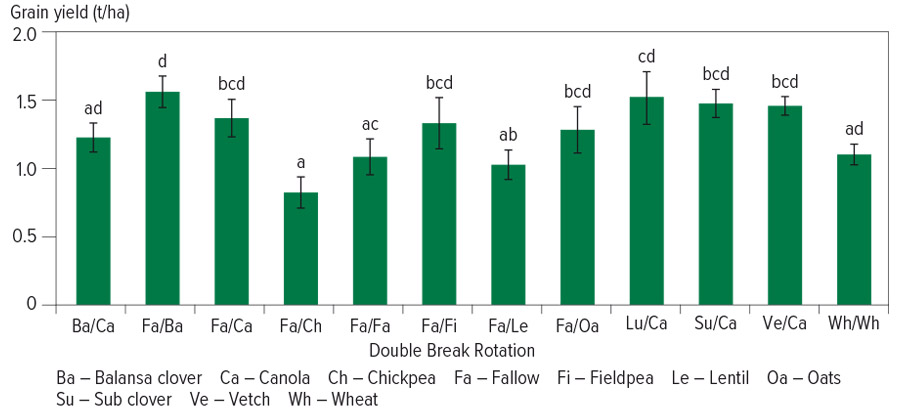

Wheat yield in 2018 was higher where fallow, canola or balansa clover were used as one of the break crops in the crop sequence (see Figure 1). In contrast, grain yield was lowest following fallow/chickpeas, fallow/lentils and fallow/fallow. Grain protein was influenced by break crop rotation, with the lowest protein occurring following fallow/oats and fallow/chickpeas. In general, grain protein was improved following treatments that had canola or balansa clover as the second break crop preceding wheat in 2018.

Figure 1: Grain yield of wheat grown after a series of double break crop rotations at the Merredin site in 2018. Error bars denote standard error of treatment mean; lower case letters denote a significant difference (P<0.05). Source:WMG

The number of ryegrass panicles in the wheat crops were significantly higher for fallow/chickpea and fallow/lentil phases (about 65 heads per square metre) compared to all other treatments (less than 30 heads/sq m). This most likely had a large effect on wheat grain yield in the following year.

“This may have been due to lower crop competitiveness and fewer options for weed control in the chickpea and lentil phases, but more herbicide options are now becoming available for growers to alleviate this issue,” Dr Craig says.

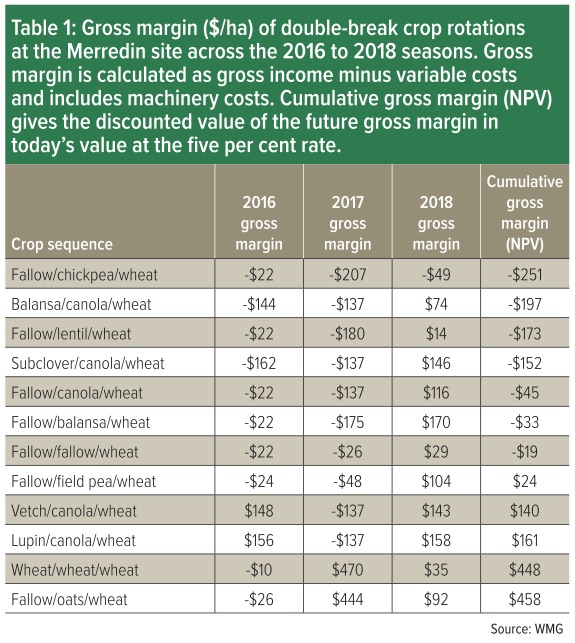

In each season, the gross margin return for each break crop sequence was calculated using the crop input data. Gross margin was calculated as the income received from the yield and value of grain per hectare based on current commodity prices, minus the variable costs associated with growing the crop (including machinery at contract rates). The cumulative gross margin was calculated as the sum of the gross margin for each year and adjusted to net present day value (NPV) by applying a discount of five per cent (see Table 1, below).

The profitability of the double-break crops, in this detailed study, was lower for all crop sequences compared with the cereal dominant crop sequences (Table 1). Growth, yield and profitability at the site was impaired due to soil acidity, severe frost events in 2016 and low growing-season rainfall in 2017, while cereal crops were less affected in 2017 and this contributed significantly to the high value of the cereal dominant crop sequences. The fallow used in this study was a spray-topped pasture, and this may have reduced the fallow benefit of increased soil moisture and lower root disease pressure, for future crop growth. The value of any grazing of pasture species balansa and subclover was not taken into account in this study.

Grower demonstration sites

Growers were encouraged to participate in this research, with three demonstration sites established in 2017 near Bencubbin, Calingiri and Corrigin. These sites were in growers’ paddocks with a history of root diseases or weed populations that a single break crop could not address, and which were sown to a break crop, pasture or fallow in 2016. In 2017, plots of up to two hectares were established using grower equipment for a range of break crops that the grower identified as options to integrate into their farming system. The remaining area of the paddock was sown to either wheat or canola depending on the grower’s paddock plan.

There was a low-rainfall season in 2017, but an effective chemical fallow in the previous year proved that successful break crops could be produced (ranging from 0.3 tonnes per hectare for lentils to 1.4t/ha for lupins) with the benefit of subsoil moisture stored during fallow. Wheat yields at the Bencubbin site following a break crop tended to be higher following a legume crop than canola.

At the Bencubbin site, a rotation of fallow/desi chickpeas/wheat was more profitable in terms of cumulative gross margin than fallow/canola/wheat, which was the grower practice at the site. This was likely due to a combination of lower soil-borne disease levels and the fixation of nitrogen. At the Calingiri site, the grower practice of canola/wheat/wheat was the most profitable sequence and at Corrigin fallow/field peas/wheat was more profitable than grower practice of fallow/wheat/wheat.

Dr Craig says there were ‘some real winners’ in terms of profitable break crop sequences across all sites. But, not surprisingly, there was no consistent break crop sequence or one legume crop that gave the best outcome given their varying suitability to different soil types and environments.

The differential between cereal dominant sequence and break crop sequence gross margin was hard to predict. In 2016, when frost was an issue at many sites, cereal crops actually yielded less than some of the break crops at the Merredin site, but in 2017, when frost did not occur, wheat and oats were well in front of the break crops. This may be due to the indeterminate growth habit of both canola and legumes which enables them to continue to flower and compensate from frost damage.

“Growers should look for local data on break crop performance, as well as experiment on-farm with different crop species best suited to their soil types and environment, to select the most profitable and effective crop sequence for their system,” Dr Craig says.

The ideal outcome is a sequence of crops that solves the paddock constraint and is also profitable. “Grower feedback on both the detailed study and demonstration sites centred around the logistics of harvesting the break crops together with concerns about the inferior weed control achieved in the high-value legumes,” he says.

These high-value legume crops were very short and had to be hand-harvested, but still yielded quite well even in a dry season. There are many tools available to help with harvesting grain legumes, such as rolling the paddock or sowing into standing stubble, depending on the farming system.

“To ensure the best outcome is achieved, growers need to be confident they have enough tools to achieve satisfactory weed control during the legume phase. With new advances in herbicide technology, this is becoming more easily achievable,” Dr Craig says.

“Storage and marketing of the high-value legumes are also important considerations. Clearly, there is a need to work further on reducing the risks of growing high-value legumes. The results are very encouraging when you get it all right.”

Early seeding into moisture is becoming increasingly important to driving higher grain yield of legumes in WA and better-adapted varieties are required for these regions.

“Both chickpea and lentils have been shown to be successful when sown as deep as 15 centimetres to use subsoil moisture,” Dr Craig says.

The West Midlands Group is now working on early and deeper sowing strategies for high-value legumes, and a successive GRDC project will focus on demonstrating the profitability of the canola/high-value legume sequence in the medium-rainfall zone of the WA wheatbelt.

More information: Nathan Craig, 08 9651 4008, eo@wmgroup.org.au