New research is underway to understand how variety and sowing time affect grain quality after rain has fallen on mature wheat crops.

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) research scientist Dr Felicity Harris is undertaking the study through the Grains Agronomy and Pathology Partnership, which is a research alliance between GRDC and NSW DPI.

The research comes after many growers suffered quality and price downgrades following wet weather before and during the 2021-22 harvest in NSW and Queensland.

“When significant rain falls on mature wheat crops, the grain may start the germination process, which reduces the falling number,” Dr Harris says. “If the germination process continues, you end up with sprouted seed.

Sprouted wheat. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“The hydration of mature grain from harvest rains causes an increase in alpha-amylase activity, which is an enzyme that breaks down starch and proteins into sugars. Wheat high in alpha-amylase can have reduced baking quality.”

The falling number test is the world standard for assessing weather-damaged wheat. It measures the number of seconds it takes for a plunger to fall through a paste of ground grain and water. The test is performed according to an internationally agreed standard.

If wheat is sound, the paste of ground grain and water is thick, and it will take the plunger more than 300 seconds to reach the bottom of the container.

For weather-damaged wheat grain, the plunger moves quickly through the paste, resulting in a low falling number.

Test error

GRDC grower relations manager Graeme Sandral says all measuring equipment, including the falling number test, has a degree of error.

“Added to this is the within and across-paddock variability of samples supplied for testing as well as varietal impacts,” Mr Sandral says.

GRDC grower relations manager Graeme Sandral. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“Where we measured falling numbers across a nitrogen experiment of Beckom wheat, we found the experimental error to be about 30 seconds above or below the mean result.

“If the falling number result you have been given at the sampling stand is close to a threshold for a particular grade of wheat, asking for a second test would be a sensible option.”

Price discounts

As a grain grower herself, Dr Harris observed a relatively uniform wheat paddock produce falling number variations from more than 300 seconds to less than 250 seconds, which amounted to more than $100 a tonne difference during the 2021-22 harvest.

“That’s a high cost to bear, so there has been angst among growers who have had quality downgrades because of the wet and cool weather,” she says.

“There have been many questions from growers about storing grain to improve the chance of securing a higher premium at delivery. We don’t have any data on this, so here’s an opportunity to test it.”

In 2021, Dr Harris and her team planted a field experiment to evaluate a range of new wheat and barley varieties at Dirnaseer in southern NSW.

Like many areas, the site had more than 100 millimetres of rain combined with cool temperatures during grain filling. This will enable grain from the field experiment to be tested under varying storage conditions.

Dr Harris and her team are also running falling number tests on all 2021 cereal trials to determine varietal responses.

Storage tests

Dr Joe Panozzo, a senior research scientist working in seed phenomics and quality traits at Agriculture Victoria, is looking to determine the influence of storage time and temperature on falling numbers.

Stored grain extension specialist and farm consultant Chris Warrick, of Primary Business, and Dr Harris will provide a range of weather-damaged grain samples to Dr Panozzo for analysis.

“I’m surprised this research hasn’t been done before and it is fantastic we may be able to find answers to growers’ questions,” Mr Warrick says.

“While we were not able to provide answers for the 2021-22 harvest, it’s great to see GRDC explore these issues more deeply, so we know what to do in wet harvest conditions in the future.”

Mr Sandral says the different grain samples provided will be tested for falling numbers on the day they are received.

“Samples will be held at 20 degrees Celsius and 30 degrees Celsius in silo-like conditions to mimic storage with and without aeration cooling,” he says.

“Chris Warrick will also take some temperature measurements of on-farm storages with and without aeration cooling to determine if these lab temperatures are representative of on-farm conditions.

“All samples will be retested at regular intervals over eight months to document the impact of storage time and temperature on the falling numbers.

“We will also test if the falling numbers of different wheat varieties improve after different storage intervals and different temperatures.”

Genetic ratings

The research will build on studies led by Jeremy Curry of the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), in which falling number index ratings were assigned to wheat varieties with GRDC co-investment (see Table 1).

Table 1: Falling number index ratings for wheat (the higher the number, the less susceptible the variety is for exhibiting a low falling number).

Variety | Grade | Falling number index rating |

Bremer | AH | 5 |

Calingiri | ANW | 4 |

Catapult | AH | 6p |

Chief CL Plus | APW | 4 |

Corack | APW | 4 |

Cutlass | APW | 4 |

Devil | AH | 3 |

DS Pascal | APW | 7 |

Emu Rock | AH | 2 |

Hydra | APW | 3 |

Illabo | AH | 6p |

Impress CL Plus | APW | 2 |

Kinsei | ANW | 4 |

LRPB Cobra | AH | 2 |

LRPB Havoc | AH | 3 |

LRPB Trojan | APW | 5 |

Mace | AH | 5 |

Magenta | APW | 3 |

Ninja | ANW | 4 |

Razor CL Plus | ASW | 4p |

RockStar | AH | 3p |

Scepter | AH | 5 |

Sheriff CL Plus | APW | 4p |

Supreme | ANW | 4 |

Tungsten | AH | 3 |

Vixen | AH | 3 |

Westonia | APW | 2 |

Wyalkatchem | APW | 3 |

Yitpi | AH | 5 |

Zen | ANW | 3 |

Notes: p = provisional rating based on a single year of results.

Source: WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

An update to the WA falling number index ratings is expected based on research funded by DPIRD to support its publication of the WA Crop Sowing Guide.

Mr Sandral says the WA DPIRD research demonstrates the genetic variation between different wheat varieties for sprouting tolerance.

“For example, in Table 1, Scepter has been assigned a falling number index of 5, which is higher than Vixen, which has a rating of 3. This would indicate that Scepter is less likely to exhibit a lower falling number than Vixen,” he says.

These observations and anecdotal evidence from growers during the 2021-22 harvest add weight to findings from another GRDC investment (UOA1407-007RTX), which has shown wheat selected for boron tolerance is also less prone to low falling numbers.

Nitrogen impacts

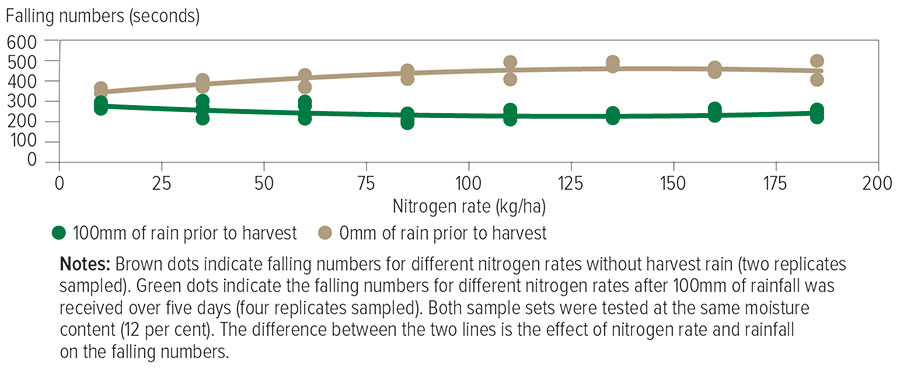

While working at NSW DPI, Mr Sandral observed high nitrogen rates applied to Beckom wheat were associated with high falling numbers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nitrogen rate and rainfall effects on Beckom wheat falling numbers.

Source: Graeme Sandral

“Our results demonstrate two important considerations,” Mr Sandral says. “The first is that the nitrogen supply to wheat can impact falling numbers. If we apply this knowledge to the paddock, we know that soil nitrogen reserves are often highly variable within and between paddocks and therefore we could expect soil nitrogen variation across the paddock to create different falling number test results.

“The second important point is that within a nitrogen rate the replicate testing (same variety, same nitrogen rate and same rainfall exposure) shows a large variation in falling number.

“At the extremes, these differences are as large as 90 seconds. For example, in Figure 1, see the green dots at 30 kilograms per hectare of nitrogen and the green dots at 60kg/ha of nitrogen.

Even after significant rainfall, some wheat varieties are more tolerant to sprouting than others. Pictured is Scepter wheat, which WA researchers found was relatively more tolerant of sprouting after rainfall than other varieties. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“Therefore, it could be reasonable to suggest this may be why we see such wild variations in falling numbers when delivering different truckloads of wheat from one particular paddock.

“For example, weather-damaged grain harvested from lighter soils that are low in available nitrogen may produce a higher falling number than low-elevation areas that are higher in soil nitrogen.

“Accordingly, there is variability caused by testing error, but there is also variability caused by varietal difference, interactions with soil nitrogen as well as differences in rainfall across the landscape.

“Additionally, heavy crops that have fallen over are likely to remain wet for longer, which is also likely to create variability in falling numbers.”

New tool

One of the frustrations at harvest is the time taken for those working in the sampling stand to perform the falling numbers test.

According to reports from growers harvesting wheat in NSW, delays of up to three hours were experienced by some growers for trucks to return to the paddock to reload.

Such delays slow the capacity to deliver wheat quickly and increase the risk for further weather damage in wet seasons as harvester drivers are required to wait until trucks return empty to deliver the next load of grain to the silo.

Dr Panozzo and his colleague Dr Matthew Hayden, with GRDC co-investment, are developing a new screening tool to detect the genetic grain defect late-maturity alpha-amylase (LMA). However, the tool can also detect whether sprouting has been triggered.

Using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging, the device allows users to quickly map the distribution of elevated enzyme activity in individual grains. This allows scientists to assign its cause to either LMA or sprouting.

“We are looking at which are the most significant spectral signatures associated with LMA and sprouting and hope to develop a portable device that can be taken to a silo,” Dr Panozzo says.

“All you would need to do is scan the grain using the hand-held device and then run an algorithm to determine if the alpha-amylase activity has been triggered, which can be caused by LMA or sprouting.”

While still under development, the device – when validated and commercialised – may offer a quick way to determine which truckloads of wheat require a more time-consuming falling number test, thereby potentially minimising delays at grain receival centres.

More information: Graeme Sandral, graeme.sandral@grdc.com.au; Felicity Harris, felicity.harris@dpi.nsw.gov.au; Chris Warrick, chris@primarybusiness.com.au; Jeremy Curry, jeremy.curry@dpird.wa.gov.au; Joe Panozzo, joe.panozzo@agriculture.vic.gov.au