Key points

- Wheat production in Central Queensland has the potential to increase by between 20 and 40 per cent if sowing dates are changed

- Research by Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries agronomist Darren Aisthorpe considered potential stressors and balanced them against crop potential to calculate optimal flowering periods

- The research found that sowing wheat in April ensures flowering and grain fill occurs more frequently under the least possible stress

Grain growers in Central Queensland have the potential to maximise wheat production by re-evaluating sowing dates.

Work by Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries senior research agronomist Darren Aisthorpe and the Regional Research Agronomy team has found that by sowing up to a month earlier, in April, wheat yields could increase by between 20 and 40 per cent.

The latest results, collected during the 2017–19 period, build on previous wheat phenology and agronomy work undertaken in Emerald since 2015. They have helped to calculate the benefits of balancing flowering and grain fill with stressful periods.

Targeting an optimum flowering period (OFP) not only increases yields but also improves grain size and reduces screenings. “It is also within the OFP that genetic advantages or differences between varieties are most able to express themselves, allowing growers to take full advantage of any improvement in yield one variety may have over another,” Mr Aisthorpe says.

He says the research has included several projects, most recently as part of the ‘Optimising grain yield potential of winter cereals in the northern grains region’ (BLG 104), a phenology project led by Dr Felicity Harris through the Grains Agronomy and Pathology Partnership involving the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries and GRDC.

Together, the projects have allowed a wide range of maturities, genotypes, sowing dates and flowering dates to be trialled and the correlation between the genetics, environment and management to be considered.

Balancing act

Mr Aisthorpe says choosing when to sow is an important consideration. In his 2017–19 trials, sowing dates were 5 April, 20 April, 5 May and 20 May, which cover the range of typical planting dates in Central Queensland.

“Northern regions will start as early as the first week in April, depending on moisture. The southern areas of Central Queensland will plant into mid-June. And, rightly or wrongly, frost risk management always ranks highly in this decision-making process. The primary aim is to choose a variety that flowers after the potential frost risk period.

“Theoretically, anthers are most sensitive to damage that can occur at temperatures up to 2°C at head height. However, factors such as the duration of the cold period, humidity and crop stress can all influence the extent of damage sustained at a given minimum temperature.”

Using data from 1900 onwards, the riskiest period in Emerald would be from late June to early August, with a risk level of less than one every 10 years. Yet, looking at the same dataset for the past 30 years (since 1990), the risk is almost negligible, but the heat stress period has tightened up.

Mr Aisthorpe says this is important to consider. “Crop stress due to extreme heat and dry conditions can have just as much effect, if not a more significant effect, on a crop yield and grain quality than frost.”

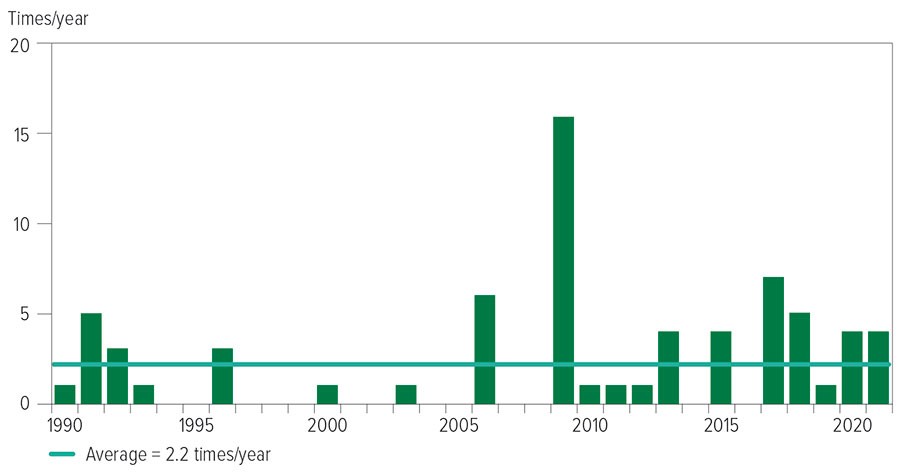

According to Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) data, Emerald Airport has only had six days with a minimum below 2oC in August since 1990. However, in the same period,19 of the past 32 years have had temperatures that exceed 30°C, with an average occurrence of 2.2 times per year.

The risk of heat stress-inducing conditions – temperatures above 30°C – historically spikes rapidly in Central Queensland at the end of August. However, as recent experiences have shown, August can be susceptible to either stress type of event, with sub-2°C events into late August, or temperatures reaching 30°C in the first week of August.”

Figure 1: Number of times temperatures exceeded 30°C since 1990 at Emerald Airport during the month of August.

Source: Darren Aisthorpe

In Central Queensland, frost and heat stress management for winter cereals is, and has always been, a fine balance between risk and reward.

“The period from head emergence to the end of grain fill is a fraught time,” he says.

This is due to several factors. Most in-crop rain falls between April and June. That means by late July and early August plants need to dig deep to pull water from the heavy clay vertosol soils. At the same time, grain fill is occurring and temperatures can vary widely.

And then there is the humidity. In the same way that high Delta-T values – that is, high temperature and low humidity – can compromise spray applications, this combination can exacerbate crop stress.

Ratio management

To assess and manage the ratio between temperature and humidity, vapour-pressure deficit (VPD or kilopascals, kPa), can be measured. This is the difference between how much moisture is in the air and how much moisture it can hold when fully saturated.

Lower VPD levels (less than 1kpa) equate to lower climate-induced crop stress. There is a quite strong correlation between higher yields and lower VPD levels.

“As temperatures increase and humidity drops, the plant will try and close the stomata on the leaves to minimise water loss, putting the plant into a state of stress if maintained for a prolonged period.”

Knowing that the average period for the most common spring wheats grown in Central Queensland to go from 50 per cent flowering to maturity is typically 40 days, Mr Aisthorpe calculated how significant VPD values for that period were on yield potential.

“Based on the VPD values alone, you would assume that the optimum period to be putting on the greatest load, that is flowering and grain fill, would be in June and July.”

This means that any wheat crops trying to flower or fill grain well into August and beyond will suffer significant yield loss relative to those crops which flowered earlier in the year.

“The biggest gains growers can make in maximising wheat production in central Queensland is to re-evaluate their sowing dates to ensure that flowering and grain fill take place during the lowest stress period possible for the conditions.

“It is important to note that while our data clearly indicates that for lower-frost-risk regions in the Central Highlands, the OFP is in the June-July period, this may not be the case for all regions and, as such, growers must assess frost risk on a paddock-by-paddock basis. If you believe the chance of getting a frost in late June is one in two, three, five or seven years instead of one in 10, then do not target a flowering date that will put you at that elevated risk of frost damage.”

The challenge is to assess risk on a possibly paddock-by-paddock or even a bay-by-bay basis and choose a combination of all these factors, which will maximise production while minimising risk.

Changing times

For those considering changing flowering dates, Mr Aisthorpe says this can be done in one of two ways.

“Adjust the sowing date of your current varieties to target the optimum flowering period or change the variety if you are reluctant to plant any earlier than you do currently.

“From a systems standpoint, early sown wheat tends to have a better chance of getting follow-up rain to get secondary roots down and will compensate much better if establishment is suboptimal, especially if deep-sown.

More information: Darren Aisthorpe, 07 4991 0808, darren.aisthorpe@daf.qld.gov.au