Key points

- A survey of 300 commercial paddocks across the northern region quantified soil chemical characteristics and assessed the likely limitations to legume growth

- Soil acidity in central and southern NSW growing regions is likely to be affecting potential legume production and therefore nitrogen carryover for following crops

- To address sub surface acidity issues rapidly, growers may need to consider full incorporation of lime rather than incorporation by sowing or top-dressing alone

Soil acidity in the central and southern NSW areas of the GRDC northern region is likely to be reducing the capacity of legumes to fix nitrogen in the soil, affecting potential legume production and nitrogen carryover for following crops.

Results from a survey of 300 commercial paddocks in the northern region have shown how widespread soil acidity is. This data is now helping researchers better understand the impact of this and other constraints on legume production.

Soils researcher Dr Belinda Hackney from the NSW Department of Primary Industries says one of the more immediate economic costs of acidity is its impact on biological nitrogen fixation in legumes, which reduces legume growth and soil nitrogen available for following crops. “The capacity of legumes to fix nitrogen can considerably reduce fertiliser input costs for the farming system, but it requires legumes and their rhizobia to achieve an effective symbiosis – that is, form effective nodules,” Dr Hackney says.

Dr Belinda Hackney. Photo: Nicole Baxter

Dr Belinda Hackney. Photo: Nicole Baxter

Researchers wanted to investigate the extent and severity of soil issues, such as acidity, in order to better understand the limitations to nitrogen fixation by legumes and to better inform regional research needs.

In 2019, the survey of paddocks on 150 farms was undertaken across four parts of the region – the central-east, central-west, south-east and south-west – to quantify soil chemical characteristics and assess likely limitations.

Within those paddocks, a minimum of 16 cores were collected over a representative area of about 2500-square-metres. Each soil core was divided into depth segments of 0 to 5cm, 5 to 10 cm, 10 to 20 cm and 20 to 30 cm.

The paddock analyses included pH, total carbon and nitrogen, available sulphur (at all depths), available phosphorus (at 0 to 5 cm and 5 to 10 cm) and cation exchange capacity (at 0 to 5 cm and 5 to 10 cm).

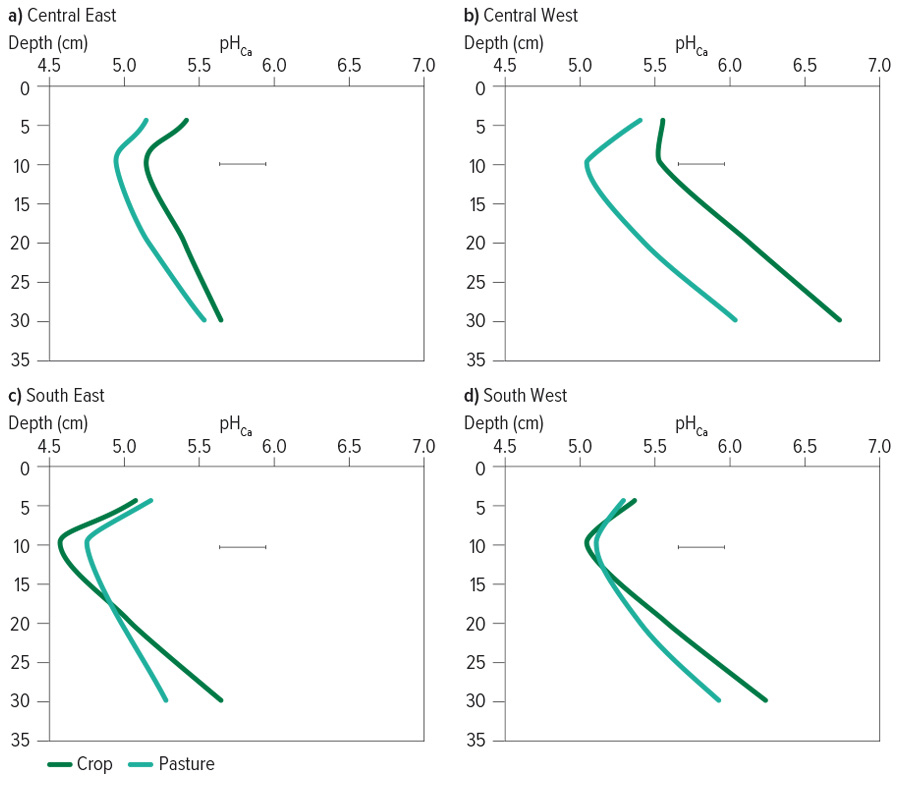

Figure 1: Surveyed paddocks’ soil acidity

Variations in topsoil pH across crop and pasture paddocks in the GRDC northern growing regions of the central-east, central-west, south-east and south-west. Three hundred paddocks were sampled in 2019. The results show that acidity appears most severe in the south-east growing region. Source: Dr Belinda Hackney

Participating growers also completed a survey to understand the management of each paddock during the previous five years, including the enterprise, herbicide and fertiliser inputs, and grazing management. The paddocks’ intended future use was also detailed.

Soil acidity

Dr Hackney says a key finding of the survey was that soil acidity is a widespread issue across the four regions surveyed. “And it is likely to be impeding optimal performance of grain and pasture legumes with respect to plant growth and nitrogen fixation.”

She explains that the host legume plant and its associated rhizobia have specific tolerances to soil pH. “For most grain and pasture legumes, plant growth will not be compromised at a soil pH greater than or equal to 5.0 when measured in calcium chloride. However, for the rhizobia associated with many of the legumes, their survival and effectiveness generally begin to decline when pHis less than 5.5.

“There is a discrepancy in tolerance between the host plant and its rhizobia, and as the effectiveness of rhizobia begins to decline, the host plant relies increasingly on soil nitrogen to satisfy its nutritional requirements. As pHdeclines below 5.0, legumes may utilise more soil nitrogen than they contribute via nitrogen fixation, causing a net reduction in soil nitrogen reserves.”

Aware of this, some growers are applying lime to optimise legume growth, targeting a specific soil pH of 5.5 in most cases, she says. About one-third of those surveyed had applied lime during the past five years.

Fewer than 20 per cent of growers who applied lime practised full incorporation to a depth of 10 cm. The majority relied on incorporation by the seeder or use of a speed tiller.

However, lime applications may need to change to improve management of soil acidity. “Most growers are top-dressing lime and relying on sowing operations for incorporation. However, growers should consider tillage strategies that provide more thorough mixing of soil to a greater depth than provided by speed tilling or sowing.”

Agricultural lime is not readily soluble and when topdressed or where minimally incorporated, the rate of downward movement can be very slow, often less than 2.5cm per year. Though the rate of movement depends on soil texture, rainfall, application rates and fineness of the lime.

Strategic tillage is a way to speed up lime benefits and movement, and to address acidity in deeper parts of the soil profile.

Other findings

Dr Hackney says strategic tillage may also help alleviate the uneven distribution of phosphorus within the soil profile, seen in most paddocks sampled in this survey.

The survey found that phosphorus levels were generally above, and often well in excess of, critical levels required in the top 5cm of soil, but were often below critical levels in the 5-10cm layer.

Here researchers take a soil core on a commercial paddock. They wanted to investigate the extent and severity of soil issues in order to better understand the limitations to nitrogen fixation by legumes and to better inform regional research needs. Photo: Belinda Hackney

Here researchers take a soil core on a commercial paddock. They wanted to investigate the extent and severity of soil issues in order to better understand the limitations to nitrogen fixation by legumes and to better inform regional research needs. Photo: Belinda Hackney

This means phosphorus levels are unlikely to limit early root growth and nodulation of small-seeded pasture species that are generally sown in the top 1 cm of soil. However, there may be issues for grain legumes, which are often sown at a depth of 5 cm or more, where the phosphorus availability was lower.

Sulphur levels were generally adequate in cropping paddocks, though often not in the seed placement zone, and sulphur was frequently inadequate for legume needs in pasture paddocks.

The findings indicate that growers may need to pay extra attention to how paddocks are rotated and fertiliser requirements, Dr Hackney says.

For example, while there may be sufficient nutrients to support early root growth and nodulation for pasture legumes, this may not be the case when the same paddock is sown to grain legumes.

Soil organic carbon levels varied significantly with regions, but in general, did not differ between crop and pasture paddocks.

Dr Hackney says the survey shows there is scope to consider reapportioning inputs to address the most important issues constraining legume productivity. “On acidic soils where phosphorus levels are at, or well above, critical levels, reallocating some fertiliser expenditure towards lime application and incorporation to address acidity may be wise.”

The research forms part of GRDC’s broader work on nitrogen-fixation projects through DAN1901 002 RTX, ‘Increasing the effectiveness of nitrogen fixation in pulses through improved rhizobial strains in the GRDC northern region’. This project was co-funded by NSW Department of Primary Industries, NSW Local Land Services, Australian Wool Innovations, Meat and Livestock Australia and the Graham Centre for Agricultural Innovation.

More information: Dr Belinda Hackney, belinda.hackney@dpi.nsw.gov.au