Growers keen to avoid topsoil erosion and associated crop yield losses are encouraged to optimise crop biomass and soil nutrition decisions via soil testing.

According to agronomists in the South Australian and Victorian Mallee, this approach will help ensure good-quality stubble is retained over summer once the crop is harvested.

Nutrien agronomist Andrew McMahen says the days of the “it’s got to blow to grow” attitude are gone, with research showing that losing one millimetre of topsoil due to erosion can result in yield losses of between one and six per cent.

Historically, soil erosion has been an issue in his region around Manangatang in Victoria, but growers are farming smarter and protecting their soils in the face of tough conditions.

“In our low-rainfall area, dry years mean poor crops and little stubble cover after harvest, especially on our fragile, sandy soils,” Mr McMahen says.

“Direct-drilling practices, stubble retention and a focus on nutrition have helped us grow a stronger and more vigorous plant that tillers better and has a bigger root system to hold that plant in place over summer, or even two summers.”

Fellow Nutrien agronomist Brendan Gove is based at Mildura and says droughts in 2018 and 2019 left many growers without stubble to protect their topsoil. The region experienced windy conditions in autumn and spring, with much of the area losing topsoil.

“We’ve had a total of about nine inches of rainfall over those two years,” Mr Gove says.

“We try to look after our sandy hills and leave standing stubble there so that we can sow into something with protection.”

He says the issue for many growers on tight budgets following poor seasons is the cost of nutrient inputs to replenish soils and the gamble of losing this investment in another dry year.

“Following erosion in recent years, the soil has gone back to where it was 15 to 20 years ago, and the lack of soil and nutrition in some parts of the paddock is holding us back,” he says.

Both agronomists are working with growers, through a GRDC investment, demonstrating the importance of soil and plant testing to inform profitable fertiliser use. Led by Agronomy Solutions, they have been soil and plant testing and running fertiliser strip trials to assess the economics behind best-practice procedures where there has previously been a knowledge gap.

Soil testing

Re-

“We’re pretty focused on nutrition with our sands, with nitrogen and sulfur being important, but also with phosphorus at sowing,” Mr McMahen says.

“Variety choice is also important as we need to seek varieties known for good-quality stubble.

“Nutrition is probably the biggest factor for us, however, as it doesn’t matter what variety you choose – if you don’t have your nutrition right then you’re not going to produce a decent crop, which is then going to leave a pretty poor stubble and cause issues with wind erosion.”

You might expect eroded areas of the paddock to have depleted nutrient levels, but the need for nitrogen and phosphorus applications may be lower than anticipated.

Trials conducted in drought-affected areas of South Australia and Victoria in 2018 and 2019, which included trials run across Mr McMahen and Mr Gove’s regions, showed that low production zones were often associated with low extractable phosphorus.

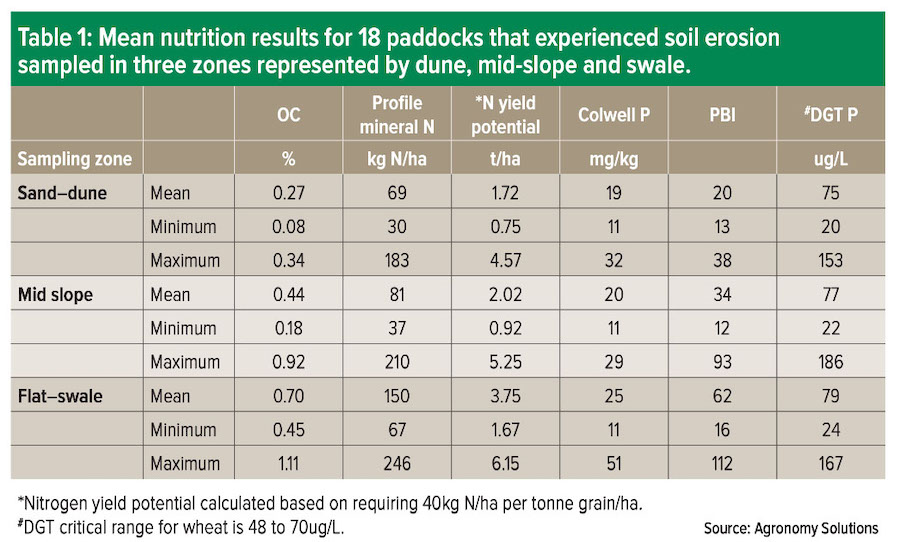

But the GRDC study also found the soil nitrogen status was higher in poor areas compared to the productive zones, suggesting the low crop yields of the previous season resulted in nitrogen carryover. The levels of carryover nitrogen were sometimes enough to grow wheat crops that yielded two tonnes per hectare (Table 1, below).

Sand dunes have very low organic carbon levels and are heavily reliant on nitrogen fertiliser inputs to meet crop nitrogen demand in a good season. But the GRDC study revealed reasonable carryover of mineral nitrogen following a poor winter and spring, and a typically dry summer.

Rotations and fertiliser strategies

Mr Gove says considering the crop rotation is crucial in managing nutrition and maintaining soil integrity.

Mr McMahen says growers in the northern districts are growing more lentils and vetch in their rotations and, while this was adding nitrogen to the soil, these often lack early vigour and ground cover.

“We are concerned if there is low stubble from the previous season and a legume is planted, because the paddocks will be more prone to wind erosion,” he says.

“On top of that, the legumes themselves don’t leave much stubble after they are harvested.”

It is important to grow a good stubble before planting grain legumes and to be flexible with your paddock plans if this does not occur, Mr McMahen says.

Additionally, he says sheep grazing will threaten soil integrity and make areas of paddocks more prone to erosion. The most effective management option is to remove the stock from the paddock, particularly from sand hills.

More information: Brendan Gove, 0400 027 739, brendan.gove@nutrien.com.au; Andrew McMahen, 0428 323 339, andrew.mcmahen@nutrien.com.au

Useful resources:

GRDC - Stubble Initiative; Soil Testing YouTube video playlist