Key points

- Integrated pest management (IPM) adoption needs boosting

- ‘Knowledge cards’ with ecological pest facts are available from GRDC

- Knowledge and forecasting of beneficial insects could be a key IPM tool

Integrated pest management (IPM) combines multiple strategies for managing insect pest outbreaks. These include detection and monitoring, effective and selective chemical use, and undertaking practices that avoid problems occurring in the first place.

To this end, GRDC invested in a five-year project with CSIRO – in partnership with cesar, the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (DPI), South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) and the University of Melbourne – to identify the knowledge gaps that are holding back adoption of IPM, to address these gaps and to design novel, user-friendly resources.

Five key gaps were identified:

- What causes pest outbreaks?

- What factors affect abundance and intermittent pest status of transient pests (such as earwigs and millipedes)?

- How should we monitor for pests?

- What are the impacts of natural enemies on pest numbers in the field?

- Which species are important as pests or natural enemies?

- When, where will they strike?

Predicting when and where invertebrate pests will reach high densities and cause damage that results in yield loss in grain crops is a challenge. It is only by making many observations over time and at multiple locations that we can begin to understand the environmental factors that influence populations. Studying interactions between pests and the crop, or predation by beneficial insects, is difficult in the field, so we often use ‘microcosm’ or laboratory studies. Through these studies in both the field and microcosm, the project has generated knowledge on the life cycles, crop damage potential and distribution across the southern grain growing regions of Bryobia mites, slaters, millipedes and earwigs.

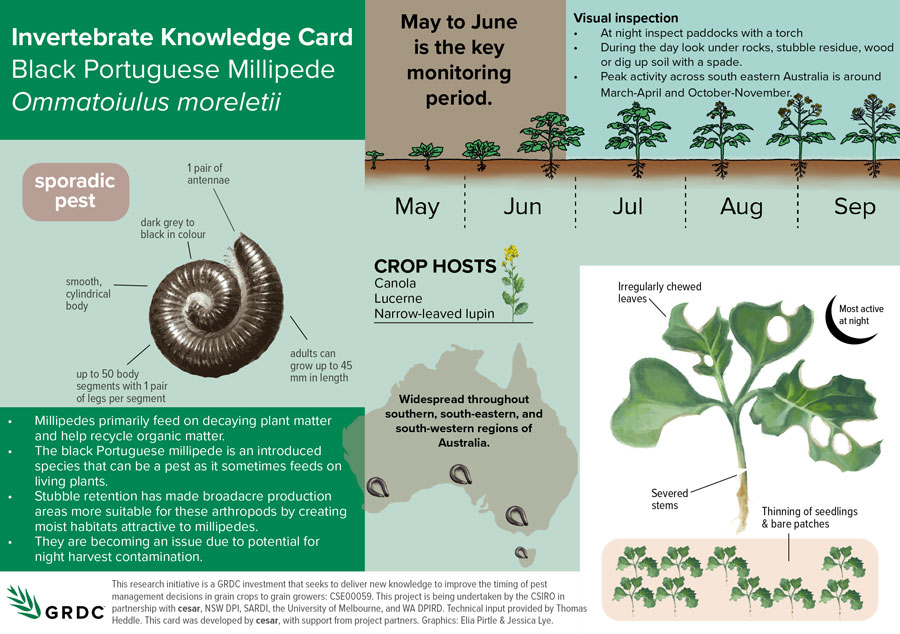

In the case of earwigs, we also identified that nearly all earwig species are omnivorous (herbivore pests that are sometimes predatory), with only common brown earwig (Labidura truncata) solely a beneficial predator. Our trials have shown that lucerne and canola seedlings are the most vulnerable to earwig damage. This information is now available through GRDC as a series of ‘invertebrate knowledge cards’, such as the example shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: An example of an invertebrate knowledge card. This one explains the life cycle, crop damage potential and distribution of black Portuguese millepede (Ommatoiulus moreletii).

Source: GRDC

Integrating control measures

Effective IPM is not just about understanding what causes pest outbreaks; it is also about understanding the impacts of natural enemies that assist in controlling pests. The studies on parasitoid wasps by Samantha Ward for her GRDC-supported PhD studies have shown just how much these beneficial insects contribute in the fight against aphids, often without us knowing.

Field cage studies across multiple regions showed effective aphid pest suppression by beneficial insects, including lacewings, ladybird beetles and parasitoid wasps. It is therefore important that pesticide management regimes consider potential impacts on these allies. We are finalising further studies into the effects of neonicotinoids insecticides on beneficial insects.

Impacts of beneficial insects?

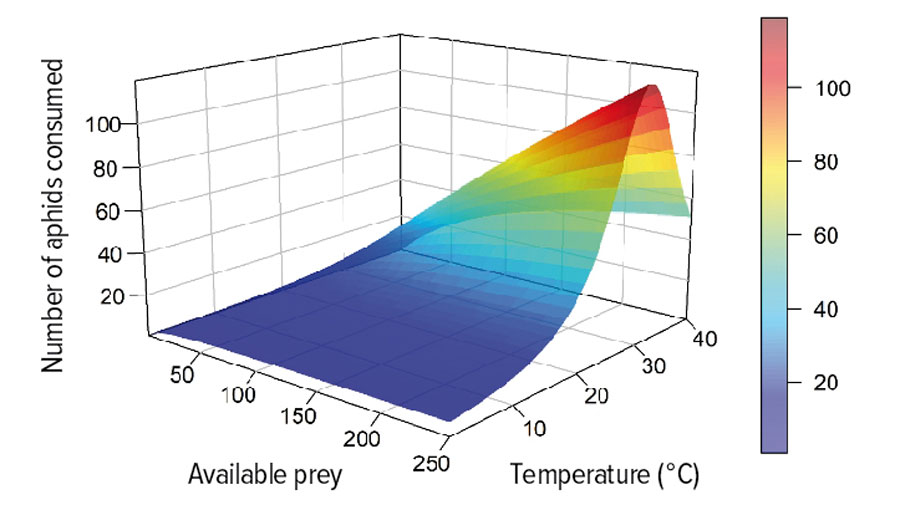

Laboratory studies on the consumption rate of aphids by ladybird beetles have allowed us to quantify the combined impacts of initial aphid density and temperature on the predicted number of aphids consumed.

This data, along with data from many other studies, has been used to inform the development of a computer simulation model. The model provides valuable insights into key drivers that affect aphid populations and their control by beneficial insects. It is an important step towards ‘digital IPM’ – decision tools that are fully integrated with automated monitoring and forecasting from such models.

A reinvigorated effort is required to boost IPM practices to ensure the sustainability and profitability of the Australian grains industry. This will be achieved by applying new knowledge about pests and their enemies that could be used to control the pests and by deploying digital IPM decision tools to assist in monitoring, forecasting and decision-making for smarter pest control.

Figure 2: Laboratory data used to create a model to show increasing consumption of aphids by ladybirds as temperature and number of available prey increases.

Source: CSIRO

More information: Dr Hazel Parry, CSIRO, 07 3833 5681, hazel.parry@csiro.au