After being detected in the Torres Strait only weeks earlier, the fall armyworm (FAW) arrived on mainland Australia in February this year.

The moth, which has started to become a global concern in recent years, is native to tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas. It was first reported outside its native range in Africa in 2016, followed by the Middle East, Asia and now Australia.

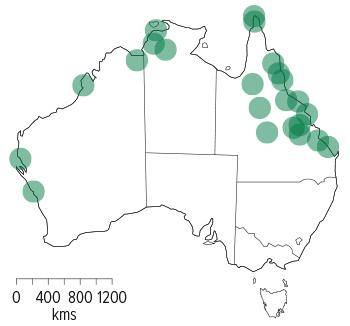

This map represents a selection of Australian detections of adult moths in pheromone traps. It is not exhaustive. Larvae have been found in crops in only a subset of these locations. (As at 28.7.2020) Credit: cesar

It is now considered established in parts of Queensland, the Northern Territory, and Western Australia. In late July it was also detected as far south as Geraldton in Western Australia (see map).

Part of GRDC’s response has been to invest in a project investigating FAW biology, spread and establishment potential, as well as options for improving industry capability to manage the pest now and into the future.

Led by cesar’s Dr Olivia Reynolds, it began in April. Dr Reynolds says it is important to remember that FAW can be managed. “Through a gap analysis, priority research, development and extension activities have been identified and several are underway to inform preparedness and best management practices.”

An industry continuity plan is also being developed. It will include assessments such as pest biology, seasonality, dispersal capacity (including potential non-crop plant host range), potential plant industry impacts, management options, diagnostics and surveillance protocols.

Which crops are affected?

Although grasses including maize and sorghum are favoured by FAW (Spodoptera frugiperda), the pest reportedly feeds on many hosts – by one estimate, more than 350 species from 76 plant families, although many of these remain unvalidated.

With this in mind, the project is conducting a ‘deep dive’ into these reported hosts to produce a validated FAW host plant list. Internationally, FAW reportedly also causes economic damage to rice, pearl millet, cotton, turf and fodder crops.

FAW occurs as two predominant strains and hybrids thereof. One is a ‘rice strain’ (R strain), the other a ‘corn strain’ (C strain). The R strain is thought to preferentially feed on rice and various pasture grasses, while the C strain mainly feeds on maize (corn), cotton and sorghum.

Historically, the pest has been classified as either rice-preferred or corn-preferred FAW. However, recent genomic studies have confirmed the presence of hybrids in both native and invasive ranges, leading to gaps in knowledge about host crop preferences, mating behaviour and pesticide resistance.

FAW completes its life cycle in about five weeks in optimal temperatures. In Australia it will be able to complete multiple generations in a year, particularly in the subtropical and tropical climatic regions of northern Australia.

One of the big questions for the Australian grains industry is: where will FAW go?

Dr Reynolds says that using international FAW data, coupled with Australian climatic data, the population growth potential of FAW in Australia is estimated to increase during the warmer months and decrease during the colder ones. However, compared to other countries, Australia’s unpredictable rainfall will also contribute to population activity potential, particularly in the more arid interior.

It is predicted that northern Australia, particularly regions closer to the coast, can support permanent year-round populations.

However, population growth potential will retract and expand based on climatic variability and changes to suitability.

In south-eastern, southern and south-western Australia, initial modelling suggests that the conditions most favourable for population activity will typically span November to March. However, assuming migration from more northern regions, population build up may occur during September and October as observed for other moth pests, such as Helicoverpa punctigera, which has a similar thermal biology to FAW.

Climatic variation between years, such as warmer and wetter springs may be conducive to earlier infestation and movement. For example, certain pulses and even green winter cereals may be at some risk in spring through the more southerly migratory range. Similarly, wetter summers and warmer autumns may result in later persistence into autumn and extended return migration.

Beyond climate, Australian non-commercial and native plant hosts of FAW will support population build up outside of cropping areas and will play a crucial role in determining industry impacts. This highlights a key gap in current knowledge in Australia. Existing knowledge and experience managing other moth pests, such as Helicoverpa armigera and punctigera will be important for growers, acknowledging there will be differences in host preferences.

In regions that are not predicted to sustain year-round populations, migration will be an important factor. “While there may be times that are conducive for population growth, this will depend upon migratory populations successfully moving into and exploiting these regions,” Dr Reynolds says.

She says that gaining an understanding of FAW’s host-range, migratory biology and behaviour will be important in identifying effective management and monitoring strategies for both FAW and its natural enemies.

Triggers for migration

Although quick to point out that they are not experts in FAW per se, with this pest new to Australia, leading entomologists Professor Peter Gregg and Dr Garry McDonald can offer additional insights into how FAW may migrate across Australia.

Professor Gregg is an agricultural entomologist and insect ecologist at the University of New England’s School of Environmental and Rural Science, while the University of Melbourne’s Dr McDonald is a grains pest entomologist.

Dr McDonald, who completed a PhD in the common armyworm (Mythimna convecta), says that as food dries up, the weather warms and the winds change, noctuid moths – similar to FAW – start to get ‘edgy’. In a synchronised event triggered by these environmental conditions, the moths start to move.

“The moths recognise the tail end of a high-pressure system where the winds get stronger and more turbulent. They fly vertically up into the low-level jet stream,” he says.

From there, the moths can move vast distances. Often their flight will end with a synchronising event such as a cold front.

“They have evolved a strategy that works for them. With rain, brought from the cold front, comes fresh plant growth and this concentrates them across favourable breeding areas. They mate and lay eggs; the young larvae are not initially apparent but, as they grow, particularly dense populations may move en masse together.”

Professor Gregg, an expert in Helicoverpa punctigera (native budworm or Australian bollworm) says moths can travel 10 to 15 kilometres an hour, but with wind assistance they can go much faster. “It means they can cover several hundred kilometres if they have the winds and they may fly for more than one night,” he says.

“In the US, FAW migrates from southern Texas and Florida up to the north-eastern parts of the country and into Canada over several generations. But, for us, they are in northern Australia at the moment and migration is expected to occur southwards when conditions are favourable.

“FAW is only just establishing itself in Australia and while the predictions help us to prepare, the reality of its distribution and migratory patterns will become evident over the coming months and years.

“At the end of the day, FAW is a migratory pest and it is spread all around the world and a good deal of that migration has to be long-distance migration.”

Professor Gregg says a further difference between Australia and northern America is temperature.

“In northern America, the temperature is the main driver of migration. It pushes FAW northward in the summer. In Australia it will be rainfall changes – both seasonal and unpredictable rain – not temperature, that will spur them to move. Most of Australia is warm enough for most insects. Also, our rainfall is much more irregular and that will drive FAW migration patterns.”

Fortunately, Dr Reynolds says, investigations undertaken in the current project have made considerable progress in understanding FAW migration potential. “Over time, the ability to make accurate predictions will improve as more data is added to our stockpile of knowledge about how FAW interacts with Australian ecologies and climates,” she says.

“Understanding and building the capability to predict moth flight will be an important aspect of current and future research and will aid surveillance and management decisions.

“Our work has taken into account potential economic impacts, geographic range, affected crops and pest biology, and considered these in a management context, including resistance profiles and similarity to existing endemic pests.”

Crop damage

Dr Reynolds notes that there has been little FAW damage reported to wheat worldwide. “That is likely due, at least in part, to the winter period in which much of this crop is grown.”

In maize, however, damage can depend on crop stage. Seedlings can be more susceptible than late-whorl-stage corn. “The plant generally becomes more resistant as it moves towards tassel. However, after tassel, the ears [of maize] are very susceptible.”

Dr Reynolds says that one important aspect of FAW management will be the need to inspect vegetative sorghum and maize.

Internationally, particularly in the Americas, planting maize early is recommended to reduce FAW damage. “However, in Australia, soil temperature is a constraint for maize planting in the subtropical and temperate regions. A minimum soil temperature of 12°C is required for successful crop establishment.”

In northern NSW, maize is typically planted between September and November, while in the tropics, maize can be planted almost year-round in coastal areas. In inland regions, such as the Atherton Tablelands, crops are typically planted from July to August, with later plantings from November to January. Where feasible, early planting could offer increased protection against FAW.

Dr Reynolds says the extent of plant tolerance to damage caused by FAW depends on a variety of factors, including the quality of the seed, the variety, plant nutrition, water availability, soil health and the growth stage attacked. “These are key factors in the consideration of plant susceptibility or tolerance to FAW damage. As research progresses it will continue to inform best management practices.”