Key points

- Cowpea weevils – or bruchids – are an important insect pest in stored pulse crops in tropical and subtropical Australia

- They can be effectively controlled using label rates of phosphine fumigant in sealed silos over a minimum period of seven days

- No major differences in tolerance to phosphine were identified in 15 populations collected from multiple Queensland locations

Cowpea weevil (also known as bruchids) is a damaging pest of a wide range of stored pulses, such as mungbeans (pictured) and chickpeas, in the tropics and subtropics. Photo: Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

Cowpea weevil (also known as bruchids) is a damaging pest of a wide range of stored pulses, such as mungbeans (pictured) and chickpeas, in the tropics and subtropics. Photo: Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

A new study sheds light on the efficacy of phosphine control of cowpea weevil, or bruchids, in mungbeans and chickpeas.

There is growing demand for high-quality, insect-free Australian pulses such as mungbeans and chickpeas in the Indian subcontinent and Middle East. To meet the required quality standards and protect trade opportunities, it is critical for growers to protect harvested pulses from insect attack during storage.

While much is known about controlling pests that are typically associated with stored cereals, less is known about pulse-specific insects such as the cowpea weevil (Callosobruchus maculatus). These insects, commonly known as bruchids, can damage a wide range of stored pulses in the tropics and subtropics.

Phosphine fumigation is the only chemical treatment registered for pulses and has the advantage of being accepted by markets as a residue-free treatment. Although recommendations for fumigating cereal pests are based on extensive laboratory and field research, research on pests specific to pulses is limited.

The Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) recently investigated the effectiveness of phosphine fumigation of cowpea weevil. This research addressed key questions relating to the relative susceptibility of different life stages, treatment regimes and potential resistance in local populations.

How much is enough?

DAF investigated two critical factors affecting fumigant efficacy against insects – time and concentration – in the laboratory using infested mungbeans and chickpeas. In other stored grain beetles, susceptibility varies across the different life stages, with eggs and pupae tending to be more tolerant than adults or larvae. For this reason, cowpea weevil infestations containing all life stages (eggs, larvae, pupae and adults) were used.

The research found that adults were very susceptible to phosphine, so researchers focused on suppression of adult progeny – or immature progeny that survived to adulthood – relative to untreated infestations. As expected, results showed that longer fumigation times and higher phosphine concentrations increase phosphine efficacy. But, importantly, the results showed that a seven-day fumigation at 360 to 720 parts per million (ppm) caused high levels of progeny suppression (99.7 to 100 per cent) in the test strains used (Table 1).

Table 1: The pulses were infested with all life stages (eggs, larvae, pupae and adults). All adults died and less than 100 per cent suppression of progeny represents survival of immatures (eggs, larvae or pupae) to adulthood.

Pulse | Phosphine (ppm) | Suppression of progeny (per cent) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 day | 4 days | 7 days | ||

Mungbeans | 360 | 54.7 | 90.0 | 99.8 |

720 | 69.0 | 99.8 | 99.7 | |

Chickpeas (kabuli) | 360 | 87.8 | 85.5 | 100 |

720 | 98.1 | 99.8 | 100 | |

Chickpeas (desi) | 360 | 96.8 | 100 | 100 |

720 | 100 | 97.1 | 100 | |

Source: Dr Greg Daglish

Development of resistance to phosphine is an ever-present threat, with resistance detected in all major cereal pests in Australia. DAF researchers evaluated 15 cowpea weevil populations collected from storage facilities in southern, central and northern Queensland for tolerance to phosphine. When mungbeans infested with all cowpea weevil life stages were fumigated for seven days at 360ppm, very little variation in phosphine tolerance was found. While this is reassuring, and suggests a lack of resistance, more populations need to be tested to provide certainty.

Silo fumigation trials

To confirm the efficacy of standard label rates of phosphine in the real world, researchers conducted silo-scale fumigation trials of mungbeans and chickpeas at the Hermitage Research Facility at Warwick in southern Queensland. Growers usually use aluminium phosphide tablets that react with moisture in the air, releasing phosphine gas over several days. The application rate for pulses stored at 25°C or higher is 1.5 tablets per cubic metre of silo capacity and the fumigation period is seven days.

Using these rates, mungbeans (in March 2019) and chickpeas (in March 2021) were fumigated in a nine-tonne sealable silo following the registered label for tablet formulations.

Cages containing cowpea weevil populations of all life stages were placed in various parts of the grain bulk, and phosphine concentrations were measured regularly at various locations in the silo. Fumigation efficacy was based on the number of adults that emerged in the laboratory from cages taken from the fumigated silo compared with cages from an unfumigated silo.

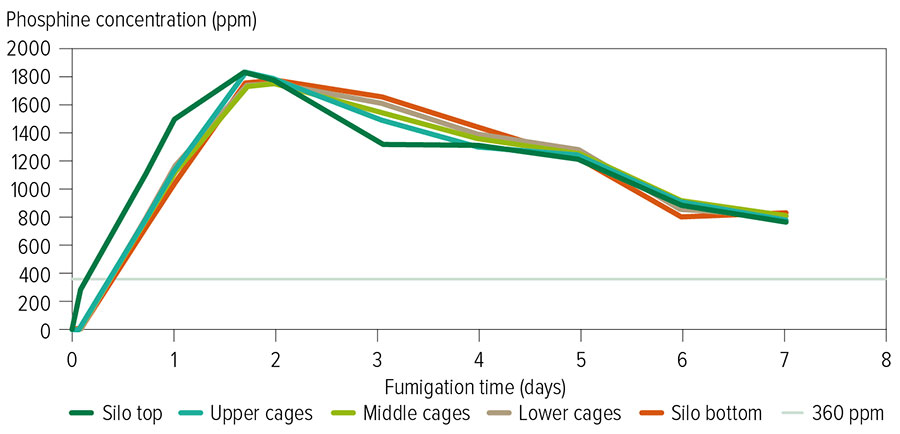

Phosphine fumigation in the silo was very effective in both the mungbean and chickpea fumigations, with a 99 to 100 per cent reduction in the number of adults emerging from the fumigated cages relative to the untreated cages. Phosphine concentration varied over time, as shown by the results for the chickpea fumigation (Figure 1), but far exceeded the concentrations that were effective in the laboratory fumigations (360 to 720ppm) for the majority of the time.

Figure 1: Phosphine concentrations measured inside a nine-tonne silo containing chickpeas fumigated in March 2021 show that fumigation for cowpea weevil was very effective. At the current label rate of 1.5 tablets per cubic metre of silo volume, phosphine concentration far exceeded 360ppm for most of the time.

Source: Dr Greg Daglish

A pattern of increase and then decline in phosphine concentration was observed in both the mungbean and chickpea silo trials, which matched the typical pattern that occurs when cereals are fumigated with phosphine. Phosphine release from tablets can take several days, and phosphine is lost progressively during the fumigation through sorption by the grain and leakage. Even well-sealed silos leak, especially through the oil-filled pressure relief valve.

This research demonstrates that cowpea weevil can be effectively controlled using standard rates of phosphine and highlights the need for growers to fumigate pulses in a well-sealed silo over at least seven days to maximise exposure of all the insect life stages to phosphine.

More information: Greg Daglish, 0481 905 650, greg.daglish@daf.qld.gov.au