Snapshot

Owners: Breil and Bernadette Jackson

Farm location: Nyngan, New South Wales

Total farm area: 7800 hectares

Area cropped: 4220ha (dryland), 280ha (irrigated)

Rainfall: 440 millimetres (long-term annual mean); 452mm (1 January to 27 July 2021)

Soil types: sandy clay loam to clay loam

Topography: flat

Soil pH: 6.8 (calcium chloride)

Enterprise: cropping

Crops grown: Sunmax, Coolah, LRPB Reliant bread wheats and Westcourt durum wheat; Pioneer® 44Y94 CL canola; PBA Monarch chickpeas; Opal-AU mungbeans

Typical crop sequence: 50 per cent cereal/25 per cent oilseed/25 per cent pulse.

Breil Jackson has a small-scale trial on the drawing board this year to compare direct heading of canola with well-timed windrowing on his family’s farm south of Nyngan in central New South Wales.

The no-tillage cropper says the move comes after replicated research trials demonstrated that direct heading of canola could offer a viable alternative to well-timed windrowing.

Breil, who crops 4500 hectares with his wife Bernadette under a 12-metre controlled-traffic farming system, first heard about the importance of well-timed windrowing through GRDC’s Grain Orana Alliance (GOA).

In 2009, GRDC asked GOA chief executive officer Maurie Street to investigate the effects of different windrow timings on canola grain oil percentage.

Mr Street discovered early windrowing resulted in grain yield penalties of up to 0.5 tonnes per hectare with minimal effects on oil. These outcomes prompted further GOA trials that explored not only optimal windrow timing, but also the fit of direct heading.

Canola can grow very tall on Breil and Bernadette Jackson’s farm. To reduce the height of the crop and improve the evenness of maturity, Breil this year started sowing canola on 20 April and increased the seeding rate from 800 grams a hectare to 1.25kg/ha. The canola pictured was a 2020 crop of Pioneer® 44Y90 CL, which averaged 3t/ha of grain. Photo: Breil Jackson

One outcome of the research was the release of a decision support tool called Canola: Windrow on Time, Reap the Reward$ to help identify the optimal time to windrow canola.

It states that the optimal time is when 60 to 80 per cent of seed from the middle third of the main stem and branches has changed colour from green to red, brown or black.

Breil, who has been a GOA board member since 2014, says knowledge harnessed from multiple research projects is captured in this “useful” decision support tool.

He now uses his self-propelled windrower to swath the crop at the optimal time and leans on his agronomist Gary Lane from Narromine to help confirm this time is correct.

Canola program

While Breil is happy to try direct heading, until this year he has preferred to windrow canola because of the size of his program.

He says swathing allows canola to be harvested more quickly. First, this is because harvesters can travel faster picking up windrows than they do when direct heading in big crops. And, second, because small areas of late-maturating crop do not delay harvest.

“If soils vary or there’s a few gilgais or depressions in the soil across one per cent of the paddock where the canola remains green, it holds up harvesting,” he says.

“Windrowing enables these areas to be pulled in and the canola harvest to be completed earlier, allowing us to move on to the wheat when it is ripe. This is important given the size of our program.”

Breil had planned to harvest 2000ha of canola this year, but 280ha had to be resown to wheat during June after mice ate canola planted on the block. This cost $14,000 in seed alone.

The Jackson family adopted no-tillage cropping in 2001 and operate under a 12-metre controlled-traffic farming system. All machinery runs along the same wheel tracks. Pictured during February 2021 is the Jackson’s crop of Opal-AU mungbeans. Photo: Nicole Baxter

The paddock, previously sown to a summer Opal-AU mungbean crop and a winter crop of wheat, was baited twice after the mungbean crop was harvested to rid the area of mice.

However, a small amount of mungbean seed left on the paddock after harvest meant the bait that was applied was not effective. Nonetheless, Breil says the bait performed well on rain-fed parts of the farm.

“We largely controlled the mice after our wheat was harvested, so I expected we would wipe them out again after our mungbean harvest,” he says.

“I’ve noticed mice seem to prefer legume grain over cereal grain and the small amount of mungbean seed left on the paddock enabled the mice to breed like crazy.”

Breil Jackson’s Opal-AU mungbeans sold for seed and yielded 2t/ha of grain, despite 30 per cent damage from frost and five per cent damage from mice. Photo: Breil Jackson

Breil Jackson’s Opal-AU mungbeans sold for seed and yielded 2t/ha of grain, despite 30 per cent damage from frost and five per cent damage from mice. Photo: Breil Jackson

The block was subsequently planted to wheat in June, but the loss of the 280ha of canola was a costly blow made even more heartbreaking because, at the time of writing, grain buyers were offering more than $740 a tonne, delivered Nyngan, for new-season canola.

“The gross margin on the canola is looking way better than Prime Hard wheat at $268/t.”

High yields

This year, Breil used his 12-metre Tobin paired-row disc seeder to plant canola heavier and later than he has done previously to reduce the height of the canola.

The single-disc seeder has 250-millimetre paired openers with 500mm between the pairs for 750mm row spacings. Seed and fertiliser are separated to prevent toxicity.

“We sowed Pioneer® 44Y94 CL, a new hybrid variety, with 60 to 70 kilograms/ha of monoammonium phosphate, into a metre of moisture,” he says.

To avoid producing crops that are more than two metres high, he increased the seeding rate from 800 grams/ha to 1.25kg/ha and pushed the start of sowing back from 15 April to 20 April.

Breil hopes this results in shorter canola crops that mature more evenly, which means less material passing through windrowers and harvesters.

To date, light sowing rates have been used to reduce risk if conditions turn dry.

Until now, he has only used direct heading in drought conditions to avoid risking canola losses caused by light windrows that tend to blow across paddocks, which makes them difficult to harvest with a pick-up front.

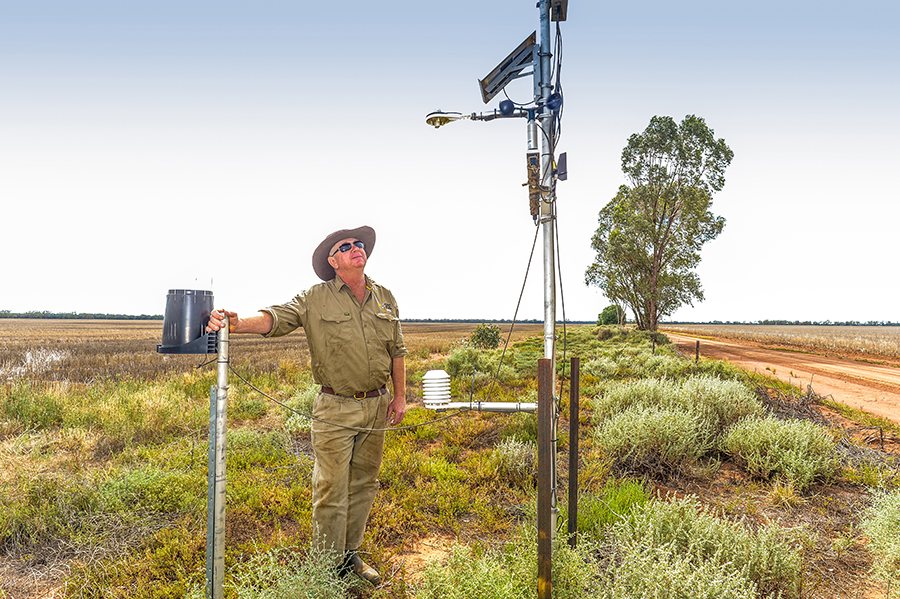

Breil has installed electronic soil moisture capacitance probes to accurately determine how much plant-available water is in the soil. His trigger point to sow canola is when there is 0.8 to 1.0m of moisture. His trigger point for sowing wheat is when there is a minimum of 0.5m of moisture. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“In drought conditions, we harvest wheat first and then move on to the canola; however, we’ve found shattering losses can be an issue in these later-harvested canola crops,” he says.

If canola is windrowed at the optimum 60 to 80 per cent colour change, Breil says it should be ready to harvest at the same time as direct-headed canola.

“The problem with this approach is that it assumes we’re harvesting evenly ripened paddocks,” he says.

“We use tramline farming, which makes it virtually impossible to go around unripe canola and come back to it for harvesting later.”

Practicality check

In 2020, Breil paid a lot of attention to the ripening of his canola and left a few patches standing that were still green because they were located in gilgais. He wanted to see how long these areas needed to ripen.

“These tiny and non-significant areas of the test paddock were still green by the time we had moved on to harvesting the windrows, which told me these areas could not be direct-headed,” he says.

Waiting for these small areas to ripen in 2020 would have meant a lot of wheat and canola would have been ready to harvest at the same time, he says, which may have led to canola shattering losses and weather damaged wheat.

Nonetheless, Breil says if this year’s canola ripens more evenly, and the direct-heading trial is successful, the family may be able to implement a combination of windrowing and direct heading.

Breil sells most of his family’s canola at harvest. Some wheat is also sold at harvest, but, if prices are low, grain is stored on-farm in bags elevated on mounds to prevent water ingress and spoilage. Breil says grain bags provide unlimited storage capacity in favourable seasons. The family has two machines to in-load and outload grain. Photo: Nicole Baxter

Like all growers, he hopes his canola, planted slightly later this season, continues to receive rain through flowering and is not affected by late frosts.

“I tend to plant a little bit later than others in our district because our frost risk is higher. All our country is low and can go underwater in a big flood year like it did in 1990, so if there’s any frost around, we tend to get it.”

More information: Breil Jackson, breil@bigpond.com