Key points

- Profit can be reduced by up to $50 a hectare for every day that canola is windrowed before it is ready

- The optimal time to windrow canola is when 60 to 80 per cent of seed sampled from the middle third of the main stem and branches has changed colour from green to red, brown or black

- A new tool is available to assist decision-making for optimal windrow timing

- Research shows direct heading is a worthwhile alternative to windrowing or can be used in combination with windrowing as a useful part of a canola harvesting strategy

- If unsure, use a small-scale on-farm test of direct heading to assess the fit for your farming system

With grain buyers offering more than $740 a tonne for new-season canola, windrowing at the right time is more important than ever for maximising profit.

Grain Orana Alliance (GOA) chief executive officer Maurie Street says multiple research projects with GRDC investment have confirmed that windrowing canola too early reduces grain yields and oil levels.

“NSW Department of Primary Industries research in collaboration with CSIRO in northern New South Wales at Tamworth, Trangie and Narrabri, as part of the Optimised Canola Profitability project, showed yield losses could be worth up to $50 per hectare per day for every day the timing is too early,” Mr Street says.

Grain Orana Alliance chief executive officer Maurie Street. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“A trial at Tamworth in 2016 demonstrated a 2t/ha difference in yield when canola was windrowed at 100 per cent seed colour change, compared to too early at five per cent colour change.”

And with new-season canola prices moving beyond $740/t delivered during July, Mr Street says the impact of early windrowing on profit could be significant.

Windrow on time

A decision support tool called Canola: Windrow on Time, Reap the Reward$ recommends the optimal time to windrow canola is when 60 to 80 per cent of seed sampled from the middle third of the main stem and branches has changed colour from green to red, brown or black.

NSW Department of Primary Industries oilseeds and pulse specialist Don McCaffery says research has shown that about 70 to 75 per cent of yield comes from the branches.

Canola: Windrow on Time, Reap the Rewards$ was released recently to help determine when canola crops are best windrowed and direct headed. Photo: Nicole Baxter

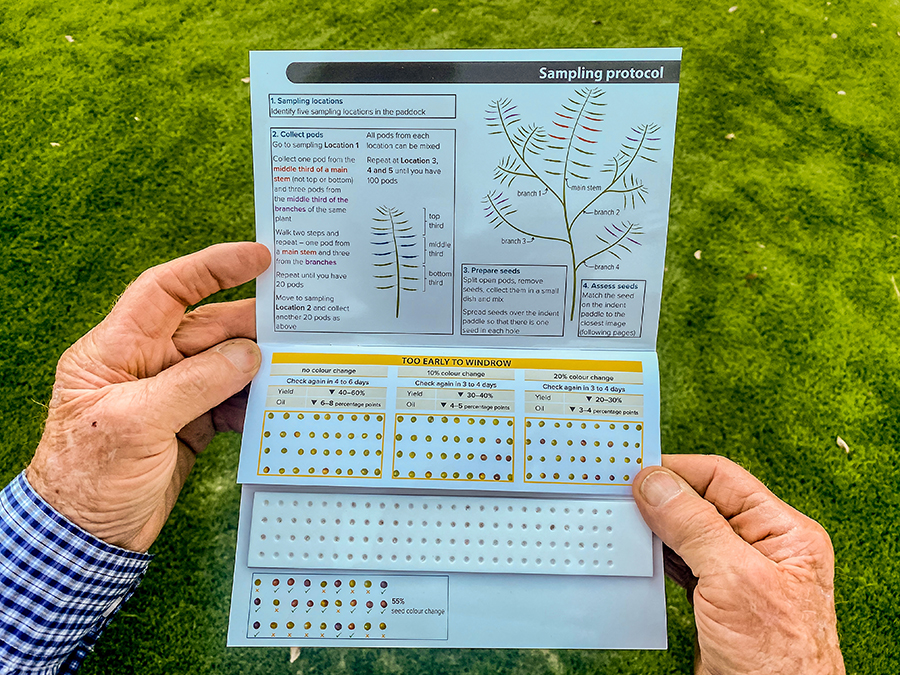

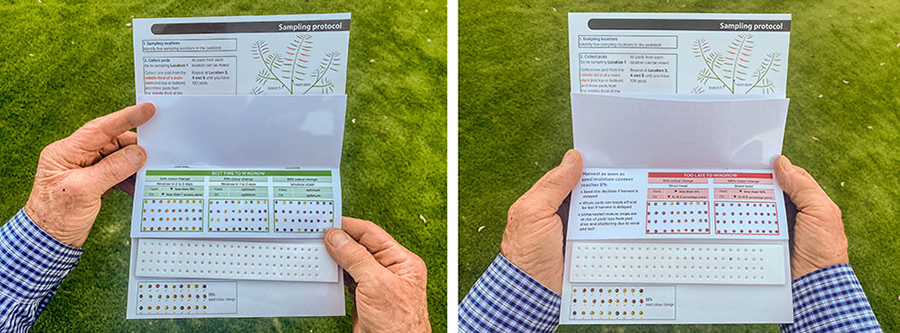

“When collecting canola pod samples, 75 per cent of all pods collected will be from the branches,” he says. “This means collecting one pod from the middle third of the main stem and three pods from the middle third of the branches of the same plant.”

According to sampling protocol outlined in the kit, the recommendation is to identify five sampling locations in the paddock and repeat the sampling process until 100 pods are collected.

Yield and oil

Mr Street says grain yield and oil accumulation happen quickly as carbohydrate moves from the stems and leaves into the seed.

“Once canola is windrowed, grain fill stops immediately,” he says. “If canola seeds are only 50 per cent of their maximum size when windrowed, they will only dry, even though plenty of green leaf and stem may remain on the plants.”

He says seed colour change – when a minimum of two-thirds of the surface of an individual seed has changed from green to red, brown or black – indicates a canola crop is reaching maturity.

“While seeds are green, they are growing in size, weight and oil, but when they start to change colour, they are moving towards maturity and growth in seed size, weight and oil content slows down,” Mr Street says.

“Seeds change colour progressively, with seed on the main stem maturing first, followed by primary, secondary and subsequent branches.”

Outlined in Canola: Windrow on Time, Reap the Reward$ is a useful sampling protocol, which recommends collecting 100 pods from five parts of the paddock. Photo: Nicole Baxter

A canola crop’s location affects the speed of maturity and colour change. Generally, canola in southern Queensland, northern NSW and northern Western Australia matures more quickly than canola in southern NSW, Victoria, South Australia and southern WA.

“What occurs with increasing levels of crop maturity is that seed pods dry and become brittle,” Mr Street says.

“Ideally, time windrowing to maximise yield and minimise losses caused by shattering canola either before – but more likely during – windrowing and harvesting.”

For more details on how to assess colour change in canola, check the protocol outlined in Canola: Windrow on Time, Reap the Reward$, which describes how to assess canola for an optimally timed windrowing program or direct heading.

Reduce pod shatter

Although windrowing canola on time is about targeting the optimum seed colour change to prevent shattering losses caused by windrowers and harvesters, Mr Street sees potential for on-farm comparisons of windrowing with direct heading.

“Over the past 30 to 40 years of canola breeding in Australia, most canola variety trials have been direct headed,” he says.

“Accordingly, the canola cultivars released are less likely to shatter except in response to extreme wind, hail or rainfall, even though this trait has not been targeted by plant breeders.

“Think about it for a moment, because if the pods on a breeding line opened at the first breath of wind, or at the first touch of a harvester, they would never make it in a yield screen and would be culled.”

Nonetheless, he says, if canola crops are windrowed too late, there is still potential for the windrower reel to strike pods, causing seed to shatter and fall to the ground.

“The benefit of direct heading is that when the reel strikes the canola pods, most of the shattered seed falls on to the draper rather than on to the ground, provided the harvester is set up to minimise losses,” he says.

“Accordingly, you may want to push your windrow timing as late as possible to optimise seed size, but not too late to risk smashing seed out on the ground where it can’t be picked up.”

A challenge to manage when windrowing, Mr Street says, is when the rate of seed colour change is extremely rapid.

“For example, this might be the case if the optimum time to windrow every canola crop on my farm is today, but I don’t have the capacity to windrow all crops today because the job will take five days to complete,” he says.

“When the window to windrow is too small and you start to windrow crops too early, it’s likely you will lose yield, with the amount sometimes a lot, or sometimes not much, depending on your location and the prevailing climatic conditions.”

Direct heading

For this reason, Mr Street sees a solid fit for direct heading when harvesting canola.

“Direct heading is based on the premise that canola is not harvested until all green seeds have started to turn black, which means all seeds within the crop have reached maturity, allowing yield and oil to be maximised,” he says.

“If you jump the gun and windrow too early, that decision might cost $50/ha for every day you go earlier than the optimum, which is a significant cost.”

Other considerations

While Mr Street favours direct heading, he says windrowing still has a place.

“If you have smaller areas within paddocks that are green and hold up direct heading, you can choose to windrow the paddock. But remember that you will sacrifice some yield in that area.”

If wet areas are five per cent of the paddock and there is only a 20 per cent yield penalty, he says, the loss associated with windrowing these areas earlier might equate to a one per cent loss on average across the paddock.

While diquat (Reglone®) is registered for pre-harvest desiccation, GOA trials over three years showed the treatment could only bring harvest forward by a couple of days.

The trials showed that often, by the time the crop could be harvested and seed had reached eight per cent moisture, any advantage offered was gone.

Direct heading of canola is a viable alternative to well-timed windrowing. If unsure, Grain Orana Alliance's Maurie Street encourages a small-scale on-farm test to determine the fit for your farming system. Photo: Nicole Baxter

GOA also tested glyphosate (Weedmaster® DST) and found the product did not accelerate canola maturity.

Accordingly, Mr Street sees a place for windrowing, but if 40 per cent of the paddock is green and the other 60 per cent is ripe, it is worth waiting until the highest-yielding part of the paddock is mature.

“In the past paddocks have been windrowed too early because they’ve been assessed according to the lowest-yielding areas, which has meant high-yielding areas have been sacrificed by windrowing them too early,” he says.

“If a paddock is very green you could be sacrificing 30 per cent of the yield, so it is best to wait and allow these areas to mature before the paddock is windrowed or, better still, direct headed.”

Weigh the risk

If a paddock has gilgais (depressions or areas where water collects), Mr Street says, an alternative approach might be to wait until the entire crop has matured for direct heading. However, this decision will depend on the area of unripe versus ripe canola.

“Keep in mind that if you windrow the paddock according to the mature areas, you’ll sacrifice yield from areas that haven’t yet matured,” he says.

“Although the right approach may be to windrow the paddock according to the later-maturing areas, some shattering losses may still occur in areas that have been ripe for a long time.”

Mixed germination

This year, on grain farms near Hillston, NSW, Mr Street says canola was planted into marginal moisture or dry soil.

“Ag Grow Agronomy and Research's Barry Haskins says his clients have reported staggered canola germinations,” he says.

“With canola crops at different growth stages, Barry reports that many of his clients are planning to direct head their crops to ensure grain yield and income is maximised.”

Contracting versus owning

In Mr Street’s opinion, direct heading avoids having to rely on a contractor to windrow canola on time.

“It can be difficult when relying on contractors to windrow a crop when every other grower in the district wants their crop windrowed on the same day,” he says.

“Having your own windrower offers the luxury of being able to wait until the canola is ready to windrow at the optimal time.

“If you own a windrower and do some contracting on the side, it might be worth preparing your clients, before you take on the work, by stating that you will be windrowing your own crops when they are ready.”

Harvest order

An argument Mr Street often hears about why windrowing is necessary is that it allows canola to be harvested before cereal crops.

“Windrowing can bring harvest forward but not as much as people think, particularly with the adoption of more timely windrowing recommendations,” he says.

“I have seen plenty of situations where I would estimate growers are windrowing more than five days too early. Delaying windrowing will close the gap between direct-headed and windrowed crops, enabling more money to be made.”

After spreading seed over a paddle with indents (supplied in the hard copy or using a homemade alternative), ensure one seed sits in each hole. Then match the seed sampled to the closest image shown. Photos: Nicole Baxter

Nonetheless, if windrowing is done early to bring harvest forward, it is worth remembering that up to $50/ha could be lost for every day crops are windrowed before they are ready.

Mr Street questions the logic of sacrificing a canola crop worth more than $740/t for a barley crop that might only be worth $180 to $200/t.

“If you leave your crop to direct head and it takes longer to ripen than you first thought, remember that if you windrow or harvest too early, you will almost certainly reduce yield and income.”

More information: Maurie Street, 02 6887 8258, maurie.street@grainorana.com.au