Research into the impact of sowing strategies on optimising yield potential has updated the ‘fundamental’ knowledge base for growers in New South Wales and Queensland.

With GRDC and NSW Department of Primary Industries co-investment under the Grains Agronomy and Pathology Partnership (GAPP), in collaboration with the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, the ‘Optimising yield potential of winter cereals in the northern grains region’ project has delivered what are considered sowing fundamentals for today’s varieties and practices across a range of environments.

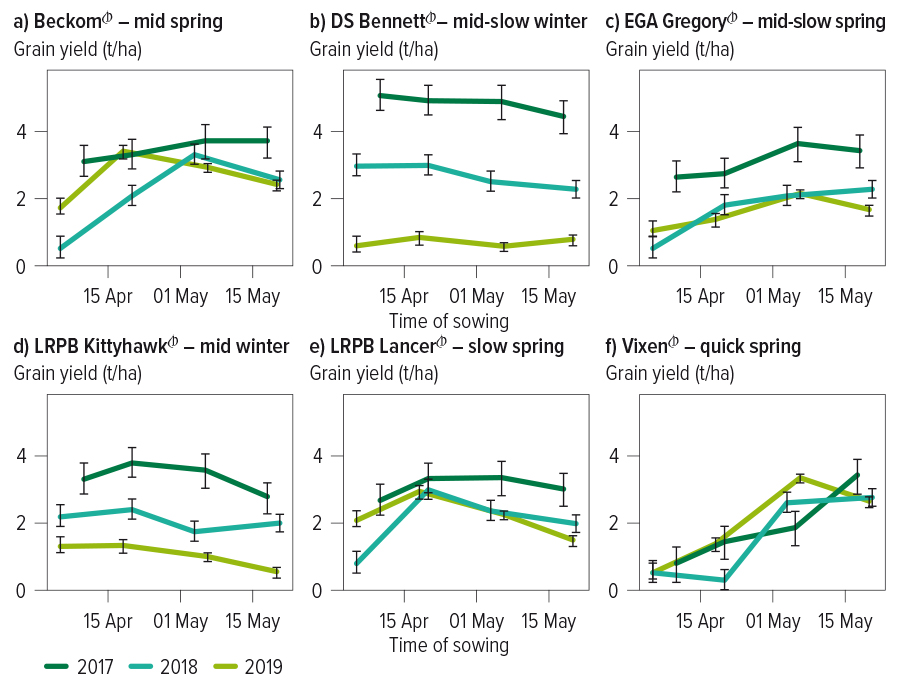

The information has been derived from three years of trials – from 2017 to 2020 – in which 36 wheat varieties were sown from early April to late May across 10 locations in NSW and Queensland. Annual rainfall across the sites ranged from 184 to 853 millimetres and grain yields ranged from 0.2 to 10 tonnes per hectare.

Sowing fundamentals

1. Understand differences in phenology

New varieties are frequently released, and it is important to understand what drives their phenology and how they fit your cropping system.

In wheat, flowering is generally accelerated under long-day photoperiods and varieties can be broadly classified into two main types: winter or spring.

Winter types can be sown early and remain vegetative for an extended period (for example, DS Bennett, LRPB Kittyhawk and Illabo. This extended vegetative period is due to the plant’s requirement for prolonged cold temperatures (vernalisation) to trigger flowering. Consequently, this ensures flowering coincides with the warmer spring conditions.

In contrast, spring types generally do not require a period of cold to trigger flowering and are suited to later sowing. However, they can have varied responses to cold. For some, exposure to cold can hasten their development (such as LRPB Lancer for others there is no effect on development (such as Vixen ). This can influence sowing recommendations.

Multiple combinations of vernalisation and photoperiod genes give a wide range of flowering response among both winter and spring types across environments and in response to sowing time.

2. Use the right variety for the right sowing date

Slower-developing winter types are suited to cooler, medium-high rainfall environments in southern NSW, which have a longer growing season and increased risk of frost. Winter types, when sown early, are capable of high water-limited yields, can extend the sowing period and can also be a useful frost mitigation tool.

However, the vernalisation requirement of these winter types makes them less suited to the warmer environments of northern NSW and Queensland, where flowering later than optimal can result in significant yield penalties due to heat stress. In contrast, quicker-developing spring types are better adapted to regions with shorter growing seasons and in environments or later-sowing scenarios where both frost and heat stress can occur in close proximity time-wise.

Despite environmental and seasonal variability, varieties that maintained stable grain yields across many sowing dates at some sites were identified and offer increased flexibility for growers (see Figure 1 and more information).

3. Stay disciplined with sowing dates – know the risk of getting it wrong

For winter varieties, a yield penalty in many mid-fast winter types was observed when sown prior to early April. This was often due to difficulties establishing crops with high soil temperatures and rapid seedbed drying after sowing. Additionally, some winter varieties’ vernalisation responses have been less stable when sown very early, resulting in early stem elongation and flowering, increasing the risk of frost damage.

Figure 1: An example of yield response to sowing time predictions for a subset of six genotypes for Wagga Wagga in 2017 and 2018 and Marrar in 2019. Vertical error bars denote the 95 per cent confidence interval.

Source: NSW DPI

Another consideration for winter wheats sown before early April and not grazed is that excessive growth under warmer conditions can increase crop water use, creating greater risk of lodging in taller crops and extended disease pressure.

For spring varieties,significant variation in phenology responses across sowing dates can also occur driven by seasonal conditions.

In general, sowing earlier than recommended increases the risk of earlier flowering and grain yield penalties due to frost damage. In later-sown crops, biomass accumulation could be limited and grain yield reduced, due to heat stress during flowering and grain fill.

More information: Dr Felicity Harris, felicity.harris@dpi.nsw.gov.au