Key points

- For the predominantly sandy soil types, ripping to either 30 centimetres or 60cm more reliably increased grain yield across all seasons compared to other soil types

- The gravelly soils responded more to the local grower solution, than to other treatments such as aggressive tillage or ploughing

- The clay soils had only a variable change in grain yield of plus or minus 0.3 tonnes per hectare across most sites in 2019 and 2020, compared to the 2018 season where there was a 0.1t/ha to 1.2t/ha increase observed

- Only six out of 63 amelioration treatments returned an economic benefit of greater than $300/ha in total from the three production years across all sites

As the success of soil amelioration techniques is becoming evident in sandier soils across Western Australia, growers are beginning to consider ameliorating gravelly and heavier soil types and a grower-driven project is proving to be a valuable guide.

The Ripper Gauge project is a GRDC-invested project in collaboration with the West Midlands Group, Mingenew-Irwin Group, Liebe Group, Corrigin Farm Improvement Group, Facey Group, Southern Dirt, Stirlings to Coast Farmers, Merredin and Districts Farm Improvement Group and South East Premium Wheat Growers Association.

The project has been managed over three years by Dr Nathan Craig from the West Midlands Group, who says the project was unique, given the grower involvement and the extent of the trials across different soil types, regions and rainfall zones.

“It was an invaluable opportunity to use a standard methodology across sites and be able to aggregate, compare data and benchmark amelioration techniques,” Dr Craig says.

We were charting new territory with this work as each site was selected based on the low amount of knowledge available on how they would respond to each soil amelioration practice within each port zone

Twenty sites were selected across the WA port zones (Figure 1) with soil types ranging from sands to loamy soils, through to gravel and sand duplexes, forest gravels and clay-based soil types.

Figure 1: Location of Ripper Gauge trials from near Geraldton in the north, down to Albany and across to Esperance.

Source: West Midlands Group

Two standard treatments were tested against a control (no amelioration) at each site: ripping to 30 centimetres or 60cm. In addition, a local grower-based solution was evaluated that often combined multiple amelioration treatments to combat a range of soil constraints. These included rotary spading, mouldboard ploughing, modified one-way ploughing, aggressive tillage (ripping and cultivation), or a mix of any of these.

Cereals dominated the crops sown at all sites in 2018, 2019 and 2020 in the first year, with sites being sown to a cereal, canola, hay or fallow in following years based on existing grower crop rotations.

Yield by soil type

Soil amelioration is intended to increase grain yield of the following crops, which directly affects crop profitability. If deep ripping, this will increase the volume of soil available for roots to explore for nutrients and water.

“As a gauge of the effectiveness of the treatments, we used the difference in grain yield from each soil amelioration treatment relative to the control at each site. This simple measure of success was easily achieved as each site was uniformly managed. We then calculated the economic benefit to the grower from soil amelioration activities across three years,” Dr Craig says.

In the first two years, there were some easily identified trends. The sites were grouped broadly by a description of soil type. For the predominantly sandy soil types, ripping to either 30cm or 60cm more reliably increased grain yield across all seasons compared to control, which supports earlier work on these soil types.

The gravelly soils responded more to the local grower solution, such as aggressive tillage or ploughing, with the grain yield benefit for all soil amelioration treatments at sites described as a gravel-based soil ranging between minus 0.7 tonnes per hectare and 0.7t/ha for both 2018 and 2019 compared to control. The large increase in grain yield observed in 2018 from maximum tillage treatments on gravel-based soil was not sustained through the 2019 season. Aggressive tillage loosens the soil, resulting in an increase in soil mineralisation and availability of nutrients in the first year or two.

The clay soils had only a variable change in grain yield of plus or minus 0.3t/ha across most sites in 2019 and 2020, compared to the 2018 season where there was a 0.1t/ha to 1.2t/ha increase observed compared to control.

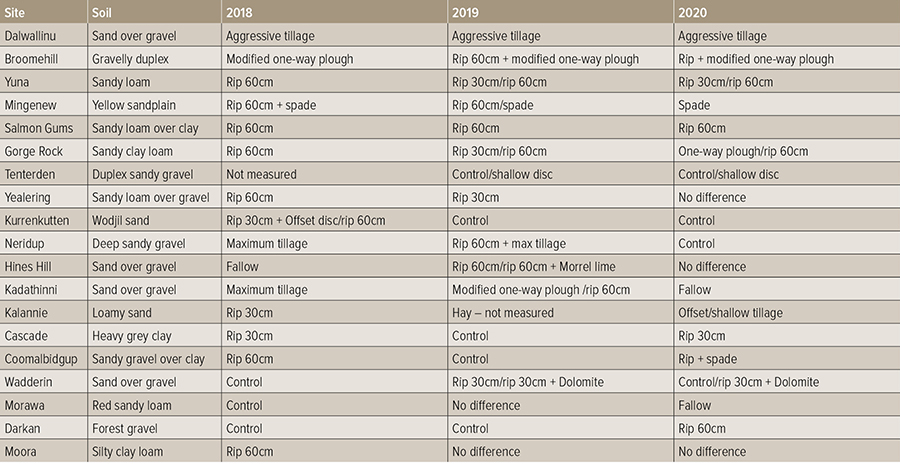

However, across the soil types for three years of crop production, some over-arching trends were observed that cut across sites and soil types. Seven out of 20 sites across the Western region, displayed a consistent benefit from one type of amelioration (Table 1). For example, at the Dalwallinu site on a sand over gravel soil, aggressive tillage was consistently the best treatment, while at Yuna on a sandy loam there was a consistent benefit from ripping, either to 30 or 60cm.

Table 1: Highest-yielding amelioration treatments over the three years of the Ripper Gauge project. One site was discontinued after year one.

Source: West Midlands Group

There were a further three sites in which a particular treatment appeared to have an immediate benefit in the first year with the effect reduced over time.

There were a further nine sites that did not have a consistent yield response to any given treatment across the three years, which presents a challenge for growers when considering the amelioration of these ‘other’ soil types.

“It is important to clarify that the highest-grain-yielding treatment can be misleading as this could have been an increase of 0.1t/ha or 1t/ha, and this has a significant impact on profitability,” Dr Craig says.

“But it does give an indication of the reliability and longevity of grain yield response for each site and soil type.”

The answer to the often-asked question ‘how do you know if the soil type will respond?’ remains elusive from the project, Dr Craig says.

Economics of treatments

The economic benefit over a three-year period was calculated as the cumulative increase in profit from increased grain yield compared to the control at each site. Initial amelioration cost was subtracted to give the net profit of each treatment (Table 2). A direct comparison of benefit for the 30 and 60cm deep ripping can be observed; however, the local grower solution was often different at each site.

Table 2: Assumptions used in calculating the net return from amelioration in this study. Cost per hectare includes fuel, repairs and maintenance, depreciation and labour costs.

| Method of amelioration | Cost/ha |

|---|---|

| Deep ripping | $73 |

| Modified one-way plough | $90 |

| Spading | $64 |

| Mouldboard plough | $184 |

| Shallow tillage | $40 |

| Aggressive tillage | $45 |

| Local grower solution | Any combination of above |

Source: West Midlands Group

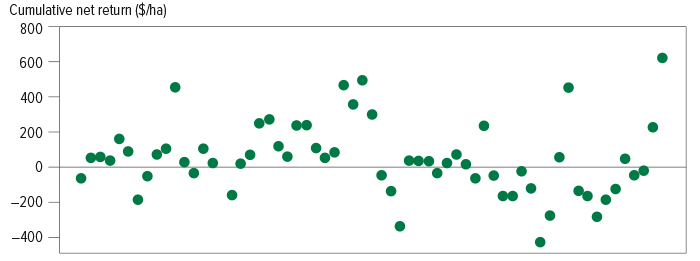

There was a positive economic benefit to soil amelioration activities for 60 per cent of soil amelioration treatments imposed across all sites (Figure 2). This gave an average economic benefit of $164/ha for the three years. Alternatively, 40 per cent of treatments resulted in a loss of $154/ha due to yield penalties associated with the amelioration activity.

Figure 2: Cumulative economic benefit or loss compared to control treatments (no amelioration, $0 return) for all soil amelioration treatments across the 20 Ripper Gauge sites for three seasons following soil amelioration.

Source: West Midlands Group

“There were only six out of 63 treatments that returned an economic benefit of greater than $300/ha in total across the three production years across for all sites,” Dr Craig says.

Timing of amelioration treatment

The Ripper Gauge project uncovered some of the practical considerations for deep ripping across the broad WA grain growing region.

Deep ripping is generally undertaken after summer rainfall in WA, when there is some soil moisture to aid penetration and to slightly reduce horsepower requirements. In addition, some soil types such as the clays and gravels are naturally hard, especially with low summer rainfall.

At two sites, soil strength was an issue that prevented conventional autumn deep-ripping practices. To combat this, the Hines Hill site was fallowed until spring to accumulate soil moisture, which benefited the deep-ripping treatment. This appeared to be a winning approach, with canola yield in the following year being doubled using this approach along with the application of on-farm lime. However, there was no difference in grain yield in the second year.

At the Moora site, a bulldozer was used as this was the only machine capable of ripping the dry, silty, clay loam soil

This soil type proved to be hard when dry and soft when wet, and in years with good growing-season rainfall, the soil softened naturally during the season to allow root growth down the soil profile. As a result, this site showed little response in each year of the study.

“Growers are encouraged to consider not just the decision to ameliorate soil, but to consider timing when conditions are most suitable. This is particularly so for deep ripping, where soil moisture is essential to aid in deeper-ripping practices and when the erosion risk is lowest.”

Additional challenges

“This project highlighted many practical issues that growers confront when ameliorating paddocks,” Dr Craig says.

Achieving accurate seeding depth across sites was also an issue that was flagged by many of the collaborating growers who were responsible for managing the trial sites. The soil conditions left by many of the amelioration treatments caused the seeding equipment to sink in the soft soil and increase seeding depth.

“While cereals can compensate for this to an extent, canola can be adversely affected.

An increase in weed numbers was an issue at many of the sites in the first year where non-inversion tillage treatments were used, particularly the intensive tillage treatments.

At these trial sites, this caused difficulties for weed management as many were sown to cereals in the first year and this flush of weeds was not expected.

“Consequently, this put pressure on the herbicide packages used at these sites and was further exacerbated by good growing-season rainfall in some areas that encouraged successive germinations of weeds that were difficult to control during the growing season.”

While the crop rotations used at each site generally were able to bring these weeds under control over the three-year period, crop rotation needed to be changed at some sites in order to achieve this.

“From this, growers have identified that canola may be a better crop to grow following soil amelioration due to the more-robust herbicide packages available, but care needs to be taken with seeding depth following soil amelioration as it is very sensitive to seeding depth.

“Like all new ideas and technologies, there are upsides and downsides that need to be managed.”

Recommendations and further work

“The results show that the treatment effects are very much site-specific,” Dr Craig says.

The greatest returns from amelioration treatments were at sites where there was a consistent benefit across the three years. Amelioration treatments that had a benefit in only one or two of the three years did not lead to an improvement in profitability.

“The trial sites have proved a great focus for grower discussions of the benefits and challenges of various soil amelioration techniques. At field walks, the practical implications of soil amelioration on these less-common soil types were a hot topic. Everyone is keen to have a go at soil amelioration; however, I advocate caution when considering investing in amelioration equipment.

If growers are looking to ameliorate less-common soil types, they should look around and see what other growers are finding that works.

“Trialling new practices and maybe hiring specialist equipment – before broader adoption – is also advised to determine the extent of the benefit, particularly as the cost of amelioration is high.”

This work will continue with new sites focusing on the effects of in-season deep ripping where the amelioration process is undertaken during the crop growing season to reduce the potential of loss of soil from wind erosion.

More information: Nathan Craig, 08 9651 4008, eo@wmgroup.org.au