Lime is a long-term investment, necessary to counter the ongoing acidification of agricultural soils. Although lime is often viewed as a variable cost it is better viewed as a capital expense – to maintain or improve a fixed asset (the soil) for future benefit.

Without lime, soil continues to acidify, eating away at yield potential and limiting rotations available to farmers. The costs compound because as the acidity yield gap increases so does the cost to close it. Lime is a necessary expense and is usually cash flow negative for the first few years, but a bit of reframing and budget management can make the investment more palatable to implement.

Treat, maintain, draw down

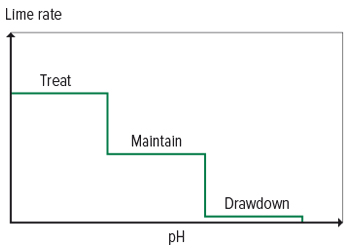

The ideal situation is to be in a liming maintenance phase (Figure 1). In the maintenance phase, soil pH is above the set targets to at least 30 cm depth. For many years now the industry has targeted a pH of at least 5.5 (CaCl2) in the topsoil (0-10cm) over a subsurface of pH of at least 4.8, although many growers are now setting their standards higher (for example, 5.8 – 6.2 over 5.2 – 5.5).

When pH is in the maintenance range, lime applications are only needed to mitigate ongoing acidification. The maintenance phase is where pH is good to depth and only maintenance applications of lime (typically 1 – 2 t/ha every 3 – 4 years) are needed to counter annual acidification caused by cropping and to ensure alkalinity continues to move down the profile to protect against subsoil acidity long-term.

Figure 1. For soil pH we want the treat phase to become the maintenance phase. Once in the maintenance phase, avoid slipping back into the treat phase.

If the pH is well above the targets (typically inherently alkaline soils) the soil is in the drawdown phase and lime is not required unless pH levels creep down towards the minimum target levels.

When pH levels are below the targets, lime is needed to both decrease acidity (which in turn will increase yield) and to mitigate ongoing acidification (which will otherwise slowly erode yields further if adequate lime has not been applied). This ‘treat’ phase is the most expensive due to the high rates and costs of lime needed and the ongoing yield gap. In the treat phase, yield is penalised every season.

This treat, maintain, watch approach for lime is similar to how the fertiliser industry has long explained applications of fertiliser, especially phosphorus fertilisers. They have also used the terms “capital” and “build up” to explain fertiliser applications when in the treatment phase.

Moving from treat to maintain

Treating acidic soil and moving into a maintenance program requires higher rates of lime and more than likely incorporating lime to depth. Maintenance applications can be topdressed but because lime can take many years to move deeper into the soil, soil acidity needs to be ‘treated’ by putting the lime at depth where the acidity is.

This requires soil testing to at least 30 cm, in a minimum of 10 cm increments. Soil pH can vary in the top 10 cm so it is a good idea to check a few 0-5 cm and 5-10 cm samples to make sure that a 0–10 cm soil test is not masking a more acidic subsurface layer.

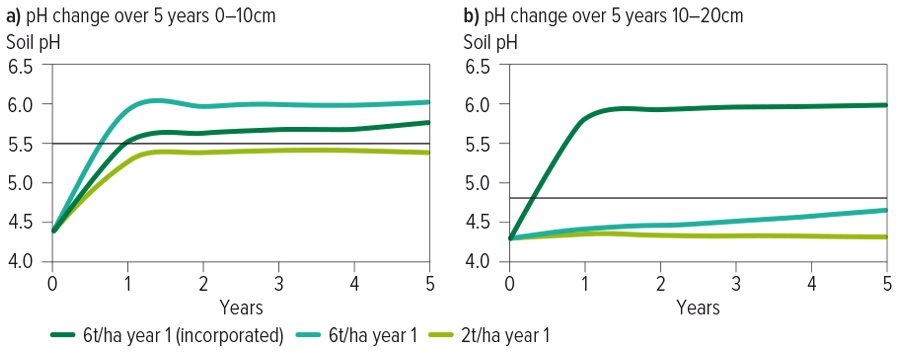

Figure 2 compares soil pH for three scenarios:

- Applying lime at 2 t/ha in year 1

- Applying lime at 6 t/ha in year 1

- Applying and incorporating 6t/ha of lime to 20 cm

The data, derived from iLime scenarios, used a sandy earth soil with pH of 4.4 in 0-10 cm, 4.3 in 10-20 cm, and 4.2 in 20-30 cm.

2 t/ha was not enough lime to put soil pH in the maintenance phase. 6 t/ha moved the topsoil from treat to maintain, but 10-20 cm was still below the recommended minimum pH. Only incorporating lime moved the top 20 cm of soil from treat to maintain.

Figure 2. pH change over 5 years in a sandy earth soil in 0-10 cm (top) and 10-20 cm (bottom) using three different liming strategies (data from iLime). Targets for minimum pH are marked with a black line. pH below the black line is in the ‘treat’ phase; above the black line is in the ‘maintain’ phase.

Only use the vegemite strategy where appropriate

Lime rates need to be high enough to treat acidity at all depths, not just the top 10 cm. The vegemite approach – a set amount of lime spread at low rates over a large area has little value. It does not treat the acidity, the yield gap remains, but the costs of lime application and spreading are still worn. Using the vegemite strategy in the treatment phase means staying in the treatment phase. The vegemite strategy is more appropriate in the maintenance zone.

Making better use of the lime budget

To get the most out of the lime budget, treat fewer hectares properly with higher lime rates and incorporate where necessary. Incorporation or strategic tillage often has co-benefits of removing other soil constraints such as compaction and mixing of water repellent topsoil and stratified nutrients.

Consider the following two scenarios:

- Using the vegemite strategy with 2 t/ha over 2000 ha.

- Treating 300 ha by incorporating lime at 6 t/ha.

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | |

| Current yield (t/ha) | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Area (ha) | 2000 | 300 |

| Lime rate (t/ha) | 2 | 6 |

| Total lime (t) | 4000 | 1800 |

| Lime cost (t/ha) | 80 | 80 |

| Total lime cost ($) | 320,000 | 144,000 |

| Mixing cost ($/ha) | - | 140 |

| Total mixing cost ($) | - | 42,000 |

| Yield change (%) | 1 | 10 |

| Post lime yield (t/ha) | 1.62 | 1.76 |

| Yield change value ($) | 7.2 | 72 |

| Yield benefit ($) | 14,400 | 21,600 |

| Total cost ($) | 320,000 | 186,000 |

| Cost minus yield benefit | 305,600 | 164,400 |

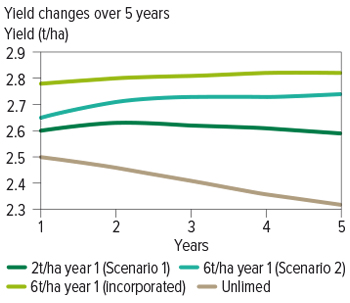

Ameliorating a smaller area properly (Scenario 2) costs less overall ($164,400 vs $305,600). The yield boost in the treated area will last for multiple seasons while other areas are ameliorated. Figure 3 compares yield for 5 years from these scenarios, using a back-to-back wheat rotation (data derived from iLime). The small yield boost from 2t/ha has been lost by year 5.

Treating a smaller area properly increases the chances of a positive cash flow on the investment in the shortest timeframe.

Figure 3. Yield changes over 5 years from three different liming strategies.

Don’t slip back into the recovery phase

Maintenance applications are critical so acidity does not slip back into the treatment phase. When acidity builds up, hydrogen ions leach deeper causing subsurface and subsoil acidity which is more expensive to treat.

Treat other issues

Of course, if there are other soil limitations to root growth like ag-induced compaction (lighter soils) or high bulk density, structureless, blocky soil (duplex and heavier soils) these need treating too. Treating acidic soil will only have a limited impact if other constraints continue to hinder root growth.

Reviewed by Steve Carr (Aglime of Australia) and Chris Gazey (DPIRD).

This article was produced as part of the GRDC ‘Maintain the longevity of soils constraints investments and increase grower adoption through extension – western region’ investment (PLT1909-001SAX). This project is extending practical findings to grain growers from the five-year Soil Constraints – West suite of projects, conducted by the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), with GRDC investment.