Key points

- Monitor your seeder when sowing to see where reef patches occur, indicated by the seeder bar chattering across the surface

- Yield maps can also help direct reefinating amelioration efforts as you can identify poor-performing areas and investigate further

- Do the financial calculations on the amelioration operation and set a budget

- Track improvements and alter nutrition if necessary pre and post amelioration by soil sampling

- Target the large obstacles first when reefinating as there are more rewards to increase trafficability and reduce driver fatigue

- Do multiple passes over smaller laterite areas to thoroughly pulverise rocks rather than spreading effort and budget over a larger area

- Weed management will be a major focus in the year following amelioration as reefinating stirs up the weed seedbank

- Crop establishment can be difficult – some growers reefinate in the pasture phase in the winter so the soil has enough time to settle before sowing the following year

- Collect and store yield maps from every harvest to compare yield benefits before and after reefinating, monitor progress and identify further patches to ameliorate

Snapshot

Owner: Scott Young

Location: Cuballing, 158 kilometres south-east of Perth, Western Australia

Average annual rainfall: 435 millimetres (370 to 400mm growing season)

Farm size: 3000 hectares

Enterprises: 100 per cent cropping (wheat/oats/barley/lupins/canola/oaten hay for export)

Soil types: white gum, salmon gum, jam and river sands

Soil pH: 5.2 average

Scott Young’s cropping land in Cuballing, Western Australia, has been plagued by a pair of interrelated soil limitations that have been a source of significant concern and loss of productivity.

Laterite reefs and outcrops form ‘caps’ on his hillsides, shedding water, posing impediments to machinery, reducing crop area and potentially harbouring weeds and pests, while low country is prone to waterlogging and salinity.

“It’s only in more-recent years that we have had access to innovative machinery that could ameliorate this laterite country,” Scott says.

The pioneer behind the innovative machinery was former Western Australian Yuna grower, Tim Pannell, who has established a company providing dedicated reefinating services to growers with equipment that is upgraded regularly to meet the conditions.

History

Scott’s father bought the Cuballing property in 1955, with Scott joining the operation in the 1980s. Prior to the purchase, about 70 per cent of the property had been cleared of the native salmon gums, mallet and parrot bush vegetation.

“We ran sheep until 2008, often agisting stock on lupin stubbles, but the seasons proved problematic for sheep, with us often having to feedlot and often losing stock to weather events, so we made a decision to de-stock, but now offer agistment,” Scott says.

This decision helped focus attention on bringing into cropping less-arable land and improving the trafficability of the paddocks.

Fifteen to 20 per cent of the property was covered with cemented laterite ‘caprock’ reefs or outcrops. Laterite is soil that is rich in iron oxide and derived from a wide variety of rocks weathering under strongly oxidising and leaching conditions. It has a conglomerate structure with a matrix of nodules and clay, thought to have formed as part of an ancient seabed.

Laterite rocks that can be smashed with a hammer are perfect for reefination; the matrix then dissolves and pebbles remain. Photo: Dr Sue Knights

Laterite rocks that can be smashed with a hammer are perfect for reefination; the matrix then dissolves and pebbles remain. Photo: Dr Sue Knights

“You can smash the rocks with a hammer, or crumble some in your hands and the matrix dissolves in water leaving the pebbles.”

The laterite reefs and outcrops were problematic on several fronts. They are sheet gravel, which sheds water, and are generally located higher in the landscape as ridges. This results in water runoff and greater seepage lower in the landscape.

“The reefs and outcrops also obstruct vehicle traffic, resulting in more obstacles and less-efficient seeding, as well as driver fatigue as operators cannot follow a line,” Scott says.

“They become weed and pest havens, as weed seeds blow into them and germinate and mice and snakes are harboured in them.

“Deep ripping this sort of country did not work, as the equipment would chatter across the surface or bring up large rocks, so we needed a different approach. The physical structure of lateritic rock makes it perfect for reefination.”

Digging deeper

Scott is a member of the 13-strong Cuballing Top Crop group that works closely with ConsultAg.

“It is a great forum for not only peer learning but also for moral support in the farming game. We share and learn from our triumphs and failures.”

In 2020, ConsultAg was contracted by GRDC to investigate optimal nutrition packages for renovated lateritic gravel to increase farm profitability. The project was managed by Ben Whisson and Garren Knell, technical aspects of the work were undertaken by Jordy Medlen and Justine Tyson. Scott joined the project to provide his property as a case study.

The project need was identified through GRDC’s National Grower Network as it was noted that growers undertaking renovating cemented lateritic gravels were unaware of the long-term changes in paddock performance after reefinating. These gravels are renowned for their high Phosphorus Binding Index (PBI), resulting in phosphorus (P) being less available for crop growth.

Fifteen newly renovated lateritic sites across Western Australia were characterised by extensive soil sampling over two seasons before and after a range of phosphorus treatments.

The main conclusion drawn from the research was that once renovated, previously cemented lateritic gravels were no different to manage than other soils with high PBI. However, it was identified that the cost benefit of renovating these soils was currently unknown on an industry scale and this was where Scott Young’s case study filled a role.

Taking a deep dive into the case study of Scott Young’s property gave Ms Medlen and Ms Tyson detailed insight into the scientific and financial aspects of the reefinating operation as they liaised with the Statistics for the Australian Grains Industry expert group at Curtin University. This group was able to undertake specialised statistical analysis of yield performance zones from Scott’s yield maps.

Operation reefination

A reefinator is a drawbar-mounted unit usually designed with a working width of three metres. It has about 10 hydraulic-mounted tynes that can rip into rocks, followed by a roller that, when fully ballasted with water, weighs 18 tonnes.

The unit is trailed at about eight kilometres per hour and the momentum also helps to smash the rock. Extra suspension is required in the tractor cab to cope with the rock-crushing conditions. It skims through layers of laterite and can take six passes or more at different directions across an affected patch to pulverise the rock.

“Reefination costs around $600 per hour – for a contract rate for an H4 machine (in 2020 this was $500/hour) – but with the present high value of land that is economic. I set a budget for reefinating each year and stop when I reach that budget,” Scott says.

He has set a target of reefinating 75 hectares, achieving about 15ha a year, and he is halfway to this goal.

By pulverising the reefs and outcrops, Scott is increasing his productive area in paddocks and can better-manage weeds on these areas, as well as seeing a productivity increase and less wear and tear on machinery.

“I am achieving more tonnes per paddock with less input as the inputs are more-evenly spread.

“I also suspect the outcrops have collected blown fertiliser and are quite fertile. Areas that previously were double-sown, due to going around outcrops, are now performing better as the plants are not competing for water.

“I am also bringing into production higher country that may not be subjected to frost, which boosts productivity. So there is a slight increase in harvested tonnage and decrease in sowing area.”

Scott yield maps at harvest every year and says these visual records are an excellent way of keeping track of the progress he is making and identifying other production issues.

“Water will now stay where the rain falls, instead of running downhill, gathering speed and eroding and causing waterlogging and salinity issues in lower-lying country.”

In these lower-lying areas Scott has been installing tile drains to direct excess water off the paddocks.

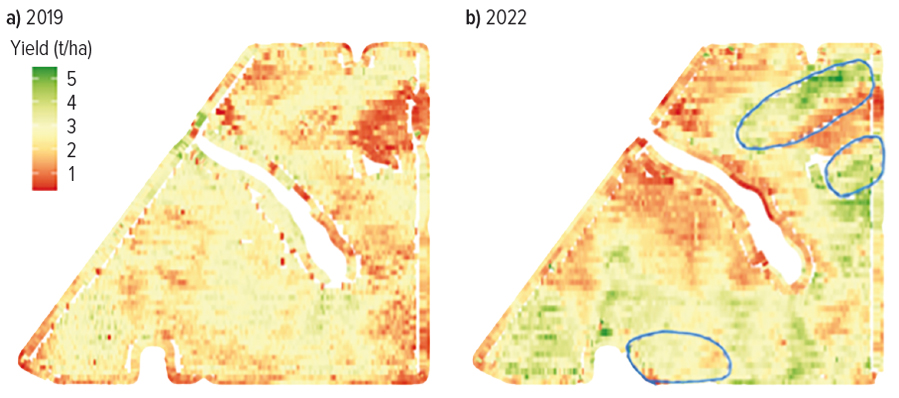

Figure 1 shows the paddock that was the subject of the study. The zones circled in blue were poor-producing gravel laterite ridges that were renovated in 2020.

“The case study involved selecting a paddock of Scott’s where we could compare three different crop rotations pre and post-renovation. In this example we were able to compare data from a lupin, wheat and barley crop pre and post-amelioration,” Ms Medlen says.

Figure 1: Heat maps of yields showing areas in Scott Young’s paddock prior to reefination (2019, a) and barley yield three years post-reefination (2022, b). Source: Scott Young

The study found that in year one post-amelioration, the lupins yielded 310 kilograms/ha less in the ameliorated zones when compared to the un-ameliorated areas.

“This was likely due to a poor seedbed in the first year. Reefinating results in soft, fluffy soil that can cause establishment issues in the first season until the soil has settled down,” Ms Medlen says.

In year two, however, when the paddock was put to wheat, there was a 620kg/ha increase (above the paddock average) and again in the third year when the paddock was in barley the ameliorated areas yielded 930kg/ha above the paddock average.

“It was interesting to note that the ameliorated zones went from below to above-average-yielding areas in year two and three.”

Prior to renovation, these zones consistently yielded below the paddock average. The opportunity cost of these zones remaining unrenovated for the three-year period was –$237 per hectare below the paddock average (Table 1). Over the three-year period for the same crop rotation post-renovation the same areas returned $394/ha above the paddock average (Table 2).

Table 1: Yield performance and financial loss for three years of different crop production prior to renovation. Source: ConsultAg and Scott Young

| Crop | Yield gain or loss (+/- t/ha) | $ per hectare at the farm gate value |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 lupins | -0.20 | -60.0 |

| 2018 wheat | -0.29 | -101.5 |

| 2019 barley | -0.26 | -75.4 |

| TOTAL | -0.75 | -236.9 |

Table 2: Yield performance and financial gain or loss for three years of different crop production post-renovation. Source: ConsultAg and Scott Young

| Crop | Yield gain or loss (+/- t/ha) | $ per hectare at the farm gate value |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 lupins | -0.31 | -93.0 |

| 2018 wheat | 0.62 | 217.0 |

| 2019 barley | 0.93 | 269.7 |

| TOTAL | 1.24 | 393.7 |

By the end of the third year, the renovated treatment almost broke even (based on the initial $500/hour cost) and the paddock is now easier to work, with less wear and tear on machinery. Over this six-year period, the renovated zones went from below-average performers to above-average, making the real economic benefit greater.

“A three-to-four-year payback compares favourably to other amelioration practices like liming,” Ms Medlen says.

The economics in this study have not considered other benefits such as reduced overlap, improved weed control and less wear and tear on machinery, which remain key drivers for reefinating.

“After renovating, water will stay where the rain falls, instead of running downhill, gathering speed and eroding and causing waterlogging and salinity issues in lower-lying country.

“Although we did not evaluate canola in this study, many growers find that canola performs well on reefinated soils because it is well-suited to these ameliorated gravel soils and achieves excellent yield.

“Canola also provides more weed-control options to help reduce the weed burdens on these soils. However, growers need to be careful to ensure good establishment and not sow too deep.”

Ms Medlen says that following reefination, you can then grow a decently profitable crop or pasture – with the added benefit that the renovated higher country will be less frost-prone and there will be an overall improvement in operational efficiency.

More information: Ben Whisson, ConsultAg, bw@consultag.com.au; Scott Young, swyoung@wn.com.au