For many growers, adequately replenishing the nitrogen supply will play a key role in maintaining productivity after a good season.

Key points

- High-yielding crops in favourable seasons export a lot of nitrogen out of the system

- Moisture levels over the summer will influence nitrogen mineralisation and availability at sowing

- Deep soil nitrogen testing remains the most-effective way to calculate the nitrogen fertiliser required ahead of sowing.

For growers lucky enough to have reaped the rewards of good conditions in 2022, nitrogen supply could be a limiting factor going into the next season. It is important to ‘take a look under the hood’ of each paddock and make sure the nutritional engine has everything it needs to hum to perfection in 2023.

Availability

Many factors influence the availability of nitrogen after a good season. High-performing crops export more nitrogen out the gate as grain, potentially leaving soils depleted. Likewise, nitrogen tie-up during stubble breakdown (known as immobilisation) can be a problem in paddocks carrying a high stubble load.

In some cases, the high cost of fertiliser nitrogen in 2022 might have resulted in nitrogen being applied at the lower end of the recommended range, which means there will be a lot of soil carbon looking for nitrogen. In this situation, an early nitrogen application is recommended to set crops up well for the season ahead, regardless of whether the season is below-average or better-performing.

When planning nitrogen requirements for 2023, start by working out how much nitrogen is available in the soil. Paddock history may not tell the full story. Pay particular attention to any paddocks that did not quite deliver on yield and protein targets, as these indicate nitrogen nutrition was not where it should be.

Rainfall events over summer will increase the amount of available nitrogen through mineralisation ahead of the season. However, too much moisture to the point of extended saturation could put soils at risk of denitrification.

The loss of nitrogen via denitrification occurs in paddocks that experience periods of water inundation leading to anerobic conditions, particularly in warmer conditions and where there is a large source of carbon. In the summer of 2010-11, large areas of Victoria that were flooded for weeks or months suffered substantial losses of nitrogen through denitrification.

The most effective way to get an accurate measure of available nitrogen and determine fertiliser needs is to undertake deep soil nitrogen testing ahead of sowing. High prices for nitrogen fertiliser increase the value of soil testing in guiding fertiliser rate decisions.

Rates and risk

Nitrogen decisions are based on the law of diminishing returns. While each dollar of nitrogen generates more than a dollar in yield, it is worthwhile. But it is important to understand how nitrogen influences protein content, and therefore, the quality grade and sale price at delivery. If high fertiliser rates lead to a bump up in the delivery grade, the rate of return can be recalculated for a higher grain value.

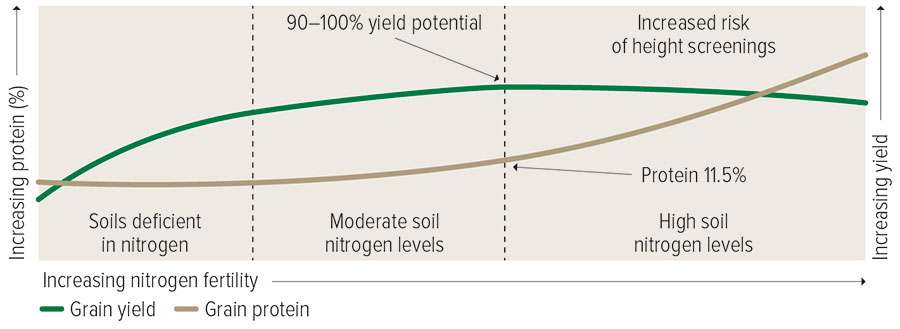

Typically crops use nitrogen to build yield to a point – usually yield plateaus when protein is about 11.5 per cent, or in the range of 11 to 12 per cent. Beyond this point, nitrogen is diverted to improving protein (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Typically crops use nitrogen to build yield to a point – usually where protein is about 11.5 per cent (range 11 to 12 per cent). Beyond this point, nitrogen is diverted to improving protein. Protein levels less than about 11.5 per cent suggest that yield has been compromised by a lack of nitrogen.

Photo: Incitec Pivot Fertilisers

Protein levels less than about 11.5 per cent can be a warning sign that nitrogen supply was limiting and crop yields were not where they should be. If milling wheat is downgraded to Australian Standard White (ASW, less than 10.5 per cent), yield has definitely been compromised.

It is ‘not in the bag until it is in the bag’, as every grower and adviser knows all too well. Fertiliser decisions are based on potential yield. If the season goes pear-shaped, reductions in yield or quality or both will reduce the return on fertiliser in that year. The influence of risk on the fertiliser decision is often influenced by each grower’s financial situation.

More information: Lee Menhenett, 0427 006 047, lee.menhenett@incitecpivot.com.au