Key points

- Summer weeds are on the move between regions in Western Australia

- 74 weed species were detected in a survey that confirmed crop and pasture volunteers continue to be the main summer weeds

- The six most-abundant broadleaf weeds were capeweed, mintweed, paddy melon, Afghan melon, small-flowered mallow and caltrop, while annual ryegrass, stink grass and small burr grass were the most common grass weeds

- There are ‘sleeper’ weeds to keep a watch on, in particular, tumbleweed

- If you cannot identify weeds, seek advice

- Manage green bridge over summer

As volatile rainfall patterns become more of a norm across Western Australia, conserving summer rainfall for winter crops needs to be prioritised by growers. But weeds have also adapted to this change and summer weeds, in particular, are on the move between regions, competing for this moisture and posing additional problems.

Growers around WA have identified this as a significant issue, particularly as new species of summer weeds are becoming more prevalent and control is becoming problematic and costly. Being able to identify these weeds to then manage them is important to conserve moisture for winter crops.

To determine the composition and distribution of summer weeds, a two-year survey was commissioned by GRDC with Andrew Storrie from Agronomo.

“Summer weeds are given a generic label, when the reality is that they are extremely diverse both geographically and over time. However, they do have some unique features,” Mr Storrie says.

Summer weeds are often very short-lived, capitalising on fleetingly available moisture and able to germinate and complete their life cycle quickly. And many of them are pioneer species, able to germinate on exposed ground.

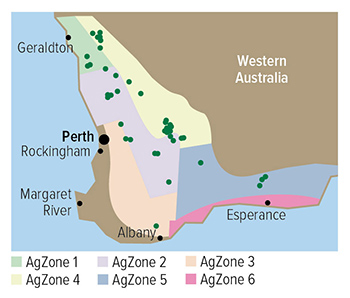

Physical surveys were conducted from late January to early April 2020 and mid-November 2020 to mid-March 2021, covering all six agro-ecological zones in the state.

Figure 1: Distribution of survey sites across south-western Western Australia. Source: AGRONOMO

Figure 1: Distribution of survey sites across south-western Western Australia. Source: AGRONOMO

“The survey work has defined the distribution and abundance of 74 weed species in the WA cropping zone and confirmed that crop and pasture volunteers continue to be major summer weeds, with 13 species found,” Mr Storrie says. “By comparison, a 2006 summer weed survey identified 45 weed species and six volunteer species.”

In the 2019-20 summer, patchy rain was received in mid-January north of Dalwallinu and east of Esperance, with more widespread patchy rain occurring in mid-February. Some areas remained dry until late March. The 2020-21 summer saw a large fall of rain in the northern and south-eastern zones in early November, then patchy rain through the summer, then more widespread rain in mid-March. Rain received in November and March was accompanied by high temperatures.

Over the two annual surveys, 57 broadleaf, 16 grass and one monocotyledon weed species and 13 volunteer crop and pasture species were identified . Volunteer crop and pasture species tended to be the most abundant and had the highest incidence. Weed abundance and diversity varied between years and agricultural zones. Eight weed species identified in 2019-20 were not found in 2020-21. Eleven weed species found in 2020-21 were not found during the previous survey. There were fewer species identified in 2020-21.

Several factors influenced weed composition and distribution, including soil texture, paddock management, crop sequence, rainfall amount and timing and temperature.

“The high prevalence of crop volunteers (three of the six most-abundant species) encourages a focus on volunteer management across the region.”

Annual ryegrass was consistently the most frequent grass species, followed by the native weed species stink grass and small burr grass. Grass diversity was generally lower than that of broadleaves, although interzone variability was less. Grass abundance was lower in 2020-21. Agricultural zone 1 was the least diverse, with four grass species, while agricultural zone 4 was the most diverse, with 12 species.

The five most-abundant broadleaf weeds were capeweed, mintweed, paddy melon, Afghan melon and small-flowered mallow. In both years, the majority of flaxleaf fleabane, wireweed and jersey cudweed (Pseudognaphalium luteoalbum) were large plants that had established in spring in the previous winter crop and had not been controlled prior to harvest.

Regional differences in species distribution were evident. Species that had a more northern distribution include tarvine , sandplain lupin, button grass (Dactyloctenium radulans) and green mulla mulla.

Table 1 shows the percentage of paddocks different weed species were found in each agricultural zone over both seasons – excluding crop and pasture volunteers, ranked by prevalence.

Table 1: Percentage of paddocks in which weed species (excluding crop and pasture volunteers) were found per AgZone averaged over both seasons. Weed species are ranked by prevalence. A cut off of 10 per cent averaged over both seasons applies and was calculated per AgZone.

AgZone | |||||||

Species | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Average % |

Paddy melon | 29.0 | 59.5 | 64.0 | 64.5 | 56.5 | 50.5 | 54 |

Mintweed | 41.0 | 47.0 | 49.5 | 25.5 | 30.5 | 62.5 | 43 |

Afghan melon | 46.0 | 50.0 | 44.0 | 43.5 | 13.5 | 41.0 | 40 |

Capeweed | 17.0 | 56.0 | 49.0 | 33.0 | 28.0 | 25.0 | 36 |

Mallow | 24.0 | 25.5 | 43.5 | 16.5 | 36.5 | 32.5 | 30 |

Annual ryegrass | 11.0 | 35.0 | 28.5 | 18.0 | 32.0 | 19.0 | 25 |

Caltrop | 26.5 | 19.0 | 7.0 | 66.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 24 |

Wild radish | 44.0 | 28.0 | 14.5 | 34.5 | 8.5 | 13.5 | 24 |

Small burrgrass | 6.0 | 49.0 | 12.0 | 3.0 | 24 | ||

Stink grass | 14.0 | 7.0 | 32.5 | 40.5 | 22.0 | 23 | |

Tarvine | 29.0 | 8.5 | 21.5 | 20 | |||

Fleabane | 18.5 | 7.0 | 16.5 | 18.5 | 34.0 | 19 | |

Flatweed | 6.0 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 7.0 | 19.5 | 27.5 | 19 |

Wild turnip | 17.0 | 18.0 | 31.5 | 7.5 | 19 | ||

Sandplain lupin | 38.5 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 18 | |||

SowthistleSonchus oleraceus | 6.0 | 8.5 | 15.0 | 7.0 | 25.5 | 40.0 | 18 |

Green mulla mulla | 26.5 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 5.0 | 17 | ||

Roly-poly | 18.5 | 9.5 | 25.5 | 7.0 | 16 | ||

Long storksbill | 6.0 | 20.0 | 11.0 | 19.0 | 14 | ||

Blackberry nightshade Solanum nigrum | 2.0 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 34.0 | 14 | |

Pigweed | 24.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 19.0 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 14 |

Wireweed | 6.0 | 7.5 | 18.5 | 22.0 | 14 | ||

Caustic weed | 6.0 | 11.0 | 16.0 | 18.5 | 13 | ||

Afghan thistle Solanum haplopetumum | 31.0 | 5.0 | 21.5 | 2.0 | 13 | ||

Barley grass | 8.5 | 16.0 | 11.0 | 12.5 | 2.5 | 10 | |

Source: AGRONOMO

Weed identification

“Weed identification is critical to inform their management,” Mr Storrie says. For example, if Afghan melon is confused with prickly paddy melon, an ineffective herbicide rate may be selected.

“There are resources available to aid identification and photos can be easily taken on mobile phones and sent to experts for assistance.”

Useful weed identification guides are available from the GRDC:

- Weeds the Ute guide. To order copies free-call 1800 11 00 44 or email: ground-cover-direct@canprint.com.au and quote GRDC Order Code- GRDC1331. https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/all-publications/common-weeds-of-grain-cropping-the-ute-guide

- Identifying Western Australian Summer weeds manual

Sleeper and problem weeds

Distribution maps, using the averaged data over two years, were made of the major weeds. These were developed to help growers and agronomists visualise the spread of the major weeds in agricultural zones and across the cropping belt. 'Sleeper weeds' is a term used to define weeds which have been present for a long time (50 years) before they actually increase in abundance and distribution.

Caltrop-Tribulus terrestris - a problem summer weed on the move. Not only poisonous for stock but its spiny burr is easily spread by machinery. Source: Kynetec incoporating Neil Clark

Caltrop-Tribulus terrestris - a problem summer weed on the move. Not only poisonous for stock but its spiny burr is easily spread by machinery. Source: Kynetec incoporating Neil Clark

Tumbleweed, is an example of a sleeper weed as it has a wide geographic distribution, yet low abundance. Under current rotations and conditions tumbleweed may not be favoured but might increase rapidly when those conditions change and needs to be watched.

As some weed species appear to be on the move, Mr Storrie encourages growers to keep their eye out for new weeds on their farms and roadsides. Green mulla mulla is becoming more common further south and readily moves into paddocks from roadsides.

“Caltrop is a problem weed as it is poisonous to sheep and has a spiny burr that enables it to be spread by machinery. It flourishes on sandier soils and creates a nightmare for growers when there is late spring rain because it can germinate and set seed before the winter crop is harvested.”

Stubble cover

This project has raised the question of the effect of stubble cover on summer weed germination. Most research has looked at the effects of stubble on weed growth and seed yield.

“Stubble may help smother summer weeds, reducing light interception and temperature. It may also provide an allelopathic effect to reduce germination. However, there is a need to determine what effect stubble type and quantity may have if any, on different summer weed species,” Mr Storrie says.

Green bridge management

Mr Storrie says green bridge management is always important but the changes in summer weed distribution and abundance emphasises the need to be vigilant.

Implications of failing to control the green bridge can have downstream effects. It is not only important to destroy the green bridge to conserve water, but also restricting any plant growth over summer can significantly reduce disease and pest carryover.

“These include both above-ground and below-ground pests and diseases, such as foliar diseases, a range of aphid species, rhizoctonia and nematodes. Failure to control early emerging summer weed species in spring can result in large weeds that are difficult to control in summer and have already set seed.”

Grazing and other management

Mr Storrie encourages growers to review their grazing programs as this may aid summer weed management.

“In enterprises that were running stock there appeared to be a wider range of summer weeds, in particular capeweed and wild radish. These systems often could not bring sufficient grazing pressure to bear to effectively manage summer weeds. The variability of summer rainfall and temperatures makes green bridge management a series of difficult decisions where livestock are involved.”

“Using clean seed and clean machinery should also be top of mind as this can avoid bringing summer weeds onto your property.”

More information: Andrew Storrie, andrew@agronomo.com.au, 0428 423 577