As harvest wraps up, Eyre Peninsula agronomist Josh Hollitt shares his advice for effective summer weed control to boost crop prospects in 2025

Eyre Peninsula (EP) agronomist Josh Hollitt borrows an adage from one of his most experienced clients when he describes the key factors in effective summer weed control: “It comes down to three things and they all begin with ‘t’ – timing, timing and timing,” he says.

Improved control of summer weeds has fuelled gains on the EP over the past decade, Mr Hollitt says. Without weeds taking up water, stored moisture can persist in soils across two or more seasons – and this has resulted in increased yields.

This impact was seen in 2023, when another of his client’s boomsprayers broke down in March as he was treating hairy panic weed. It was at least two weeks before he could get back onto the paddock; in that period, the “rocketing” weed roots drew moisture from as deep as 60 centimetres. This led to a 1.2 tonnes per hectare yield penalty in the subsequent wheat crop compared with yield in the area he had treated on time.

Mr Hollitt, of Hollitt Consulting, says there is a biological reason for the threat that summer weeds present to grain crops. All C4 plant species are “naturally tough”, drought tolerant with waxy leaves and vigorous root systems that drive deep into soils.

“There is a big difference between treating weeds two weeks after a rainfall event, which is the ideal timing, and leaving it a month when you can have roots 30 to 40cm down into the profile.”

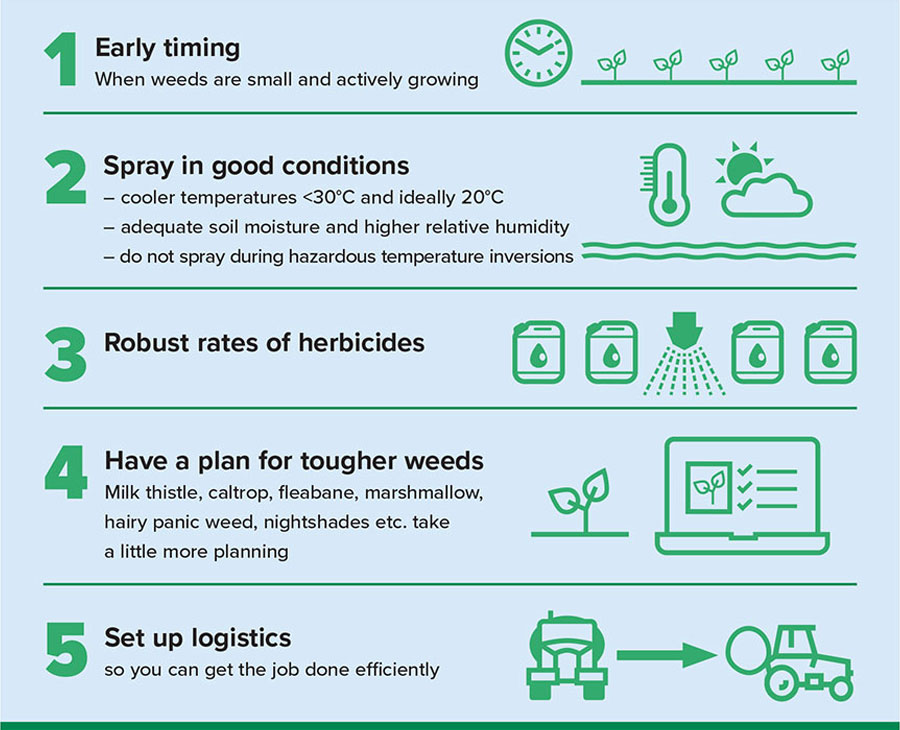

Successful summer weed control at a glance

Timely application

This moisture-drawing (and nutrient-drawing) capacity, coupled with the glyphosate tolerance that many summer weeds develop as they mature, is why timely and robust herbicide application is critical for their control, Mr Hollitt says.

Ideally, small and actively growing summer weeds should be targeted about 10 to 14 days after rain. “Smaller weeds have thinner cuticles so you’re going to get more herbicide into the plant,” he says.

Tony Cook, from the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, conducted a study on resistant milk thistle in NSW.

It showed, for example, that biomass was reduced by 67 per cent when the same rate of glyphosate (720 grams of active ingredient per hectare [ai/ha]) was applied at early rosette stage (10cm) compared with application when the weed was at mid-flowering growth stage.

“This shows that even resistant populations can be effectively controlled early, and then we can come back with optical or camera sprayers to clean up any escapes, or a double knock strategy if this technology is not an option,” Mr Hollitt says.

The timing of summer weed control should also be linked to conditions, he says. Temperature is a key factor and, if possible, treatment should start before the weather – and soil – get too warm.

Research by Dr Peter Boutsalis from Plant Science Consulting, for example, shows the impact of temperature on wild oats, where 100 per cent control was achieved in winter with 400g ai/ha of glyphosate, while the same application rate had almost no effect in summer. While wild oat is not a summer weed, Mr Hollitt says the principle is the same.

Planning and resourcing

Mr Hollitt says planning is an important factor in ensuring operations can be undertaken in optimal conditions and timeframes.

Early spring, when there is a lull in the herbicide market, is the best time to stock up, so chemicals are on hand to start summer weed control as soon as it rains after harvest. Summer spraying can also start during harvest if systems, labour and resourcing allow, or beforehand in legumes through the desiccation process.

Ideally, he says, paddocks should be kept free of weeds from harvest until seeding the following year. This is a big job requiring planning around logistics to ensure there are enough people and machinery available to complete the task: “Making sure you’re geared up and then communicating your strategy to your team is really important.”

“Getting a portion of the summer spray program tidied up before Christmas is a really good idea and takes pressure off,” he says. “Plus, starting spraying early has the added advantage of hitting smaller weeds in cooler conditions.”

Mr Hollitt says season-end planning also needs to factor in another equally critical element – a holiday break.

Seasonal conditions

This summer, with dry conditions persisting across the EP, the biggest concerns will be around tight cash flow for many operations, says Mr Hollitt. But he still urges growers not to skimp on summer weed control.

Investing in summer weed control will push budgets a bit earlier than usual because there’s unlikely to be lot of harvest income in our patch, but it will pay off in the longer term. The best operators won’t tolerate summer weeds in their paddocks because they know how much moisture and nutrients they’re drawing out and how costly that is.

Mr Hollitt says that while low rainfall usually means less weed germination, the plants that do survive are likely to be tougher and harder to kill – reinforcing the importance of tackling them before they mature.

Among the most problematic summer weeds on the EP are the glyphosate-resistant and opportunistic fleabane, late-germinating marshmallow and common potato weed. Potato weed can extract up to three millimetres a day of soil moisture when it is actively growing.

As more lentils are planted in the region, milk thistle is also emerging as a concern due to limited effective control options in-crop.

“With the majority of lentil varieties grown on the EP being imidazolinone tolerant, we only have pre-emergent herbicide options for milk thistle control due to Group B resistance. And while they are often effective early, the ‘pre-ems’ (pre-emergent herbicides) do run out of legs as the season progresses and you get late germinations that you’ll see poking up above the crop at harvest,” Mr Hollitt says. In light of these treatment constraints, prevention is key, and desiccating lentils is not just a harvest tool but also helps to curb seed-set. Mr Hollitt says summer weed control comes back to basics – the execution of a few simple jobs done well, such as hitting weeds early with robust rates in the right conditions at the right time.

More information: Josh Hollitt, josh@hollittconsulting.com.au

Resources

The $ummer Weed Tool app is a new ‘in-paddock’ app to help weigh-up the financial impact of summer weed control has been developed by GRDC and CSIRO.

By entering data on soil type, soil moisture, grain price, weed density, and fertiliser and weed control costs, the app generates information on yield benefit and return on investment for immediate versus delayed weed control.

The $ummer weeds decision support tool can be downloaded from the Apple App Store or Google Play.