Key points

- Round snails can be a serious contaminant of grain at harvest with the potential to threaten market access

- Round snail mucus is being examined for compounds that could be used to control the pest

A forensic investigation of snail slime is underway to see whether this excrement can be used as a control medium. The approach is combining improved snail ecology knowledge with sophisticated chemical analysis.

Four species of European snail are dormant on the stalks of crops during the summer, and they may pose a challenge to the harvest. These species include the white Italian snail (Theba pisana) and the vineyard snail (Cernuella virgata), known collectively as the round snails, which are the focus of investigations to identify approaches for safe removal.

Research since the early 1980s has led to a number of control methods, which are used in an integrated approach to manage snail numbers. This research has been largely centred around baiting, which is not only expensive but can also be hit-and-miss. As snails are not attracted to baits, success relies on snails encountering baits, necessitating a high density of bait spreading.

Kate Ballard on the hunt for snails and their slime in the field, Yorke Peninsula, South Australia. Photo: Scott Cummins, University of the Sunshine Coast

Snail ecology

A feature of snail behaviour that has not yet been extensively investigated is their mucus trail. Previous research on other species has shown that land snails will follow mucus trails of their own species to find a mate or to aggregate.

The question raised is: can these trails be used to lure snails into a trap?

Preliminary work on this project with the garden snail (Cornu aspersum) has revealed that the mucus trail is far more complex than its appearance suggests. With GRDC and University of the Sunshine Coast investment, this project is the first to investigate the components of snails’ mucus trails to determine whether they contain chemicals known as pheromones that may be used for communication.

Animal pheromones can be either proteins or airborne volatiles. It has been discovered that some marine molluscs use proteins as pheromones, so analysis of protein components of the mucus trail is the first step in unravelling the mystery of snail slime.

Comparison of the protein components of mucus between the breeding season (May–October) and the inactive season (November–April) will help to narrow down which chemicals are present in breeding season mucus that are not there in inactive season mucus, and therefore may function as a mating pheromone. Researchers can also get information from the amino acid sequence, which can lead a protein to be a likely candidate pheromone. To supplement this, gene expression will also be compared between the two seasons, which will provide additional information about changes in the snail during breeding season. As other terrestrial animals, including insects and mammals use airborne pheromones, the mucus trail will also be analysed for volatile chemicals. Initial analysis has already identified two promising chemicals.

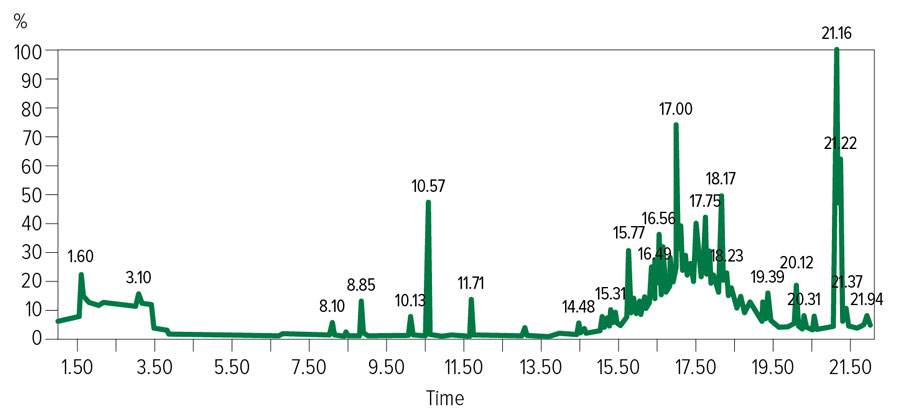

Figure 1: Gas chromatography chromatogram shows how many chemicals are present and their abundance in Cernuella virgata trail mucus.

Source: USC

Slime entrapment

Identification of an attractant pheromone may be useful in the control of snails by enticing them to a trap, similar to the lure-and-kill technique used in pheromonal insect control. Alternatively, an attractant could be incorporated to the snail baits that would make the baits more likely to be consumed by snails. Given the propensity for snails to cover a significant area of ground during the active season, the mucus trail will also be analysed for microbial components to establish whether snails play a role in the transmission of crop disease. Preliminary analysis has identified several fungal species of agricultural significance in the mucus trails.

More information: Kate Ballard, kballard@usc.edu.au