Key points

- Biocontrols are important components of integrated pest management (IPM)

- Knowledge of the distribution of parasitoid wasps and their capacity for biological control is important to inform IPM strategies that conserve them

Canola can be attacked by at least 30 species of invertebrate pests in Australia. Synthetic pesticides have been the main control agent and this single‐technology approach is likely to increase the risk of pest resistance and also harm pests’ natural enemies. However, researchers have discovered a tiny parasitoid wasp at work in Australian canola crops that is showing potential as an effective biocontrol.

Like parasites, parasitoids live at the expense of another organism (the host); however, parasitoids kill the host to complete their development. Aphid parasitoids are tiny wasps found in the insect order Hymenoptera (which includes wasps, bees and ants). These wasps require an aphid host to complete their larval development, before bursting out of the ‘mummy’ (the altered body form of the aphid host).

Samantha Ward with predator exclusion traps. Photo: Samantha Ward

Parasitoid wasps and aphids

With GRDC investment, a PhD project at the University of Melbourne focused on parasitoid wasps associated with aphids.

It aimed to understand population dynamics through the growing season, parasitoid diversity, abundance and distribution across grain production landscapes, and host associations. The aim was to determine how important parasitoids are as natural enemies of grain aphids in Australia.

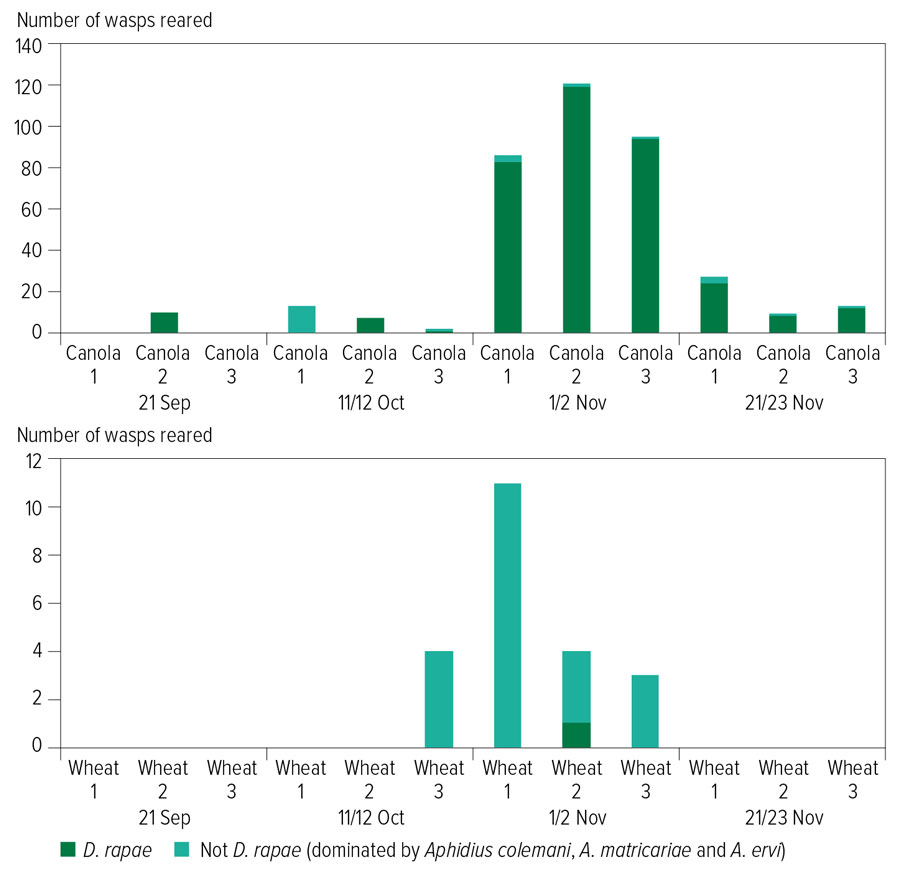

One parasitoid wasp – the cabbage aphid parasitoid wasp (Diaeretiella rapae) – dominated paddock surveys in 2016–19. This species controls many aphids but has a strong preference for brassica aphids. In the surveys it was found less at the edges of paddocks than within paddocks, and it was more common in canola than in wheat (Figure 1).

Due to the abundance of green peach aphids (GPA), variation between observed and actual rates of parasitism was investigated in canola in NSW, SA, Victoria and WA in 2019.

Figure 1: Comparison of Diaeretiella rapae numbers reared from aphids compared to other wasps in three canola paddocks and three wheat paddocks repeatedly sampled in 2018.

Source: Samantha Ward

Actual parasitism rates (in-field mummy counts) were determined by the number of wasps reared within the laboratory from all collected aphids/mummies. In-paddock counts can miss aphids that are recently parasitised, as the mummies are not visible until a few days after wasp egg-laying. Actual parasitism was 237 per cent more than what was observed in the field in most states, but four-fold in SA. This makes it clear that mummy counts alone do not provide a clear indication of actual parasitism.

The importance of wasp species as a biological control can vary depending on the crop. Diaeretiella rapae, although the dominant parasitoid found in the field, is not yet available for commercial application. However, enhancing natural populations of wasps by accepting some aphids in the crop may help aphid control. When aphid mummies are observed, it is likely that there is much higher actual parasitism happening and management decisions (for example, whether to spray) should take this into account, as well as the number of aphids.

Although wasps may not be observed early in the season, numbers can build later, along with increased rates of parasitism. This means that Diaeretiella rapae can also help control cabbage aphids later in crop development, when there is risk of aphid damage during flowering and podding.

More information: Samantha Ward, 0426 091 108, sameward1@gmail.com