Likely outbreaks of mice in Australian grain growing regions in 2023 mean that each bait grain needs to carry a lethal dose of zinc phosphide in order to ensure effective control, leading mouse researcher Steve Henry says.

Mr Henry, who has worked as a mouse researcher at CSIRO for more than a decade, told a GRDC Research Update in Bendigo that conservation tillage systems are creating an environment that is favourable for mice. Lots of food and shelter and low levels of disturbance create ideal conditions for mice.

A difficult harvest has led to significant amounts of grain being left in paddocks, providing optimal conditions for mice across southern cropping systems in the lead-up to sowing the 2023 crop, Mr Henry said. These conditions have highlighted the importance of having effective control strategies for mice to minimise the negative impact they have at different stages of the crop.

Following numerous reports from growers that baits were not working as expected, CSIRO with investment from GRDC embarked on a series of experiments to investigate potential reasons for the lack of effectiveness of the baits. “It is really important to ask questions about why things aren’t working the way they should. It is critical to have a control technique for mice that is effective,” he said.

Potential new substrates

The initial laboratory trial was carried out to identify potential new bait substrates that might be more attractive to mice. “The thinking behind this experiment was: ‘if I am a mouse living in a barley stubble, why would I transition away from safely eating barley to eating wheat with zinc phosphide on it?

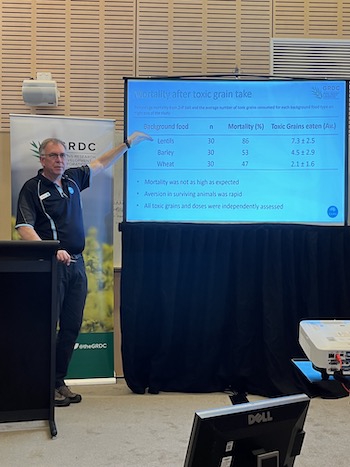

“When we identified a preferred food and offered it coated with zinc phosphide to mice in the lab we found that even though most of the mice in the study consumed the bait, we only killed half the number of mice that we expected to kill.”

Another key finding of this work was that mice that consumed a sub-lethal dose (ate the toxin and lived) stopped eating the bait. “If they get a sub-lethal dose, they are going to stop eating it,” he said. “Aversion is rapid, and the duration of aversion is unknown.”

The results of this trial raised questions about the sensitivity of mice to zinc phosphide.

CSIRO mouse researcher Steve Henry. Photo: Andrew Cooke

CSIRO mouse researcher Steve Henry. Photo: Andrew Cooke

A subsequent laboratory study undertaken by CSIRO, which investigated the sensitivity of mice to zinc phosphide, showed that mice had not become less sensitive due to frequent exposure to the toxin over the past 20 years of use, but they were less sensitive than had been reported in trials undertaken in the United State in the late 1980s. The key result of this work is that it takes two milligrams of zinc phosphide to kill a 15g mouse, not the 1g that was previously reported in the 1980s.

The results of this work have led to the provision of permits by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority to manufacture baits mixed at 50g of zinc phosphide per kilogram of wheat, instead of 25g of zinc phosphide per kilogram.

A field experiment assessing the efficacy of 25g/kg zinc phosphide baits versus 50g/kg baits was conducted on farms in the area surrounding Parkes in central New South Wales.

“Nine sites were used with three unbaited control sites, three sites baited with 25g/kg (ZnP25) bait and three sites baited with 50g/kg (ZnP50) baits. All sites were trapped prior to baiting to establish mouse population sizes and then again after baiting to determine changes in population.”

The key outcome of this experiment was that baiting with ZnP50 led to a median reduction in mouse numbers of more than 85 per cent. Modelling showed that, under similar circumstances, using the ZnP50 formulation should deliver more than 80 per cent reduction in population size most (more than 90 per cent) of the time.

In contrast, the current registered bait (ZnP25) achieved approximately 70 per cent reduction in population size, but with more variable results. “We would be confident of getting an 80 per cent reduction in population size only 20 per cent of the time if using the currently registered ZnP25 bait under similar field conditions,” Mr Henry said.

CSIRO with investment from GRDC is now undertaking work to measure the impact that background food has on the effectiveness of the bait.

“In zero and no-till systems there is lots of food and shelter for mice. It is not uncommon to hear about significant grain loss both pre- and post-harvest – in some cases up to one tonne per hectare (2200 grains/square metre). In a scenario like that with bait spread at approximately three grains per square metre, it is imperative that every grain of bait that a mouse finds is carrying a lethal dose.”

Timely application of zinc phosphide bait was “vital” for reducing the impact of mice on crops at sowing, he said. “Strategic use of bait is more effective than frequent use of bait. It is absolutely critical to reduce food in stubbles in any way that you can. If you have sheep in your system, use them to graze stubbles and reduce food.”

It was crucial for zinc phosphide to be used carefully and according to the latest advice, he said. “Zinc phosphide is the only product that growers are allowed to use for broad-scale application in crops. So it’s really important that it is used wisely to get the most effective results.”

More information: Steve Henry, steve.henry@csiro.au, 02 6246 4088