The development of rust-resistant cereals has been an ongoing research effort that has meant keeping one step ahead of ever-changing rust pathogens. In Australia, these efforts have been successful in minimising damage from new pathotypes (strains) of rust that have arisen locally.

Typically, new rust pathotypes that arise in Australia are similar to an existing one, differing only in the added ability to overcome a single resistance gene. In these cases, the new pathotype is described as being virulent for the resistance gene and any cultivar carrying that gene is then vulnerable to infection by the new pathotype.

Once virulence arises, it often spreads and becomes common.

A good example of this was the local development of virulence for the Stripe rust resistance gene Yr17 in 1999, about nine years after the gene was first deployed in Australian agriculture.

This gene was introduced to Australia by rust researchers at the University of Sydney and bred into local wheats before its first release in 1990 in the cultivar Sunbri. Since then, more than 70 cultivars with Yr17 have been released, including more than 30 cultivars that are currently grown, varieties such as:

- Cutlass

- Illabo

- LRPB Impala

- Mace

- Scepter

- Sunlamb

- Vixen.

Yr17 virulence commonplace

Virulence for Yr17 has been common and widespread in eastern Australia since 2007. For instance, nearly all samples of Stripe rust analysed for virulence in 2020 from eastern Australia had Yr17 virulence. As a consequence, this resistance gene on its own is of little value in eastern Australia. It does, however, remain effective in Western Australia.

The Leaf rust resistance gene Lr24 is another example of a rust resistance source that has been used and deployed extensively in Australia. It was first deployed in 1983 in the Torres cultivar and, since then, more than 60 wheat cultivars have been released with this gene, such as:

- Chief

- LRPB Gazelle

- Sunguard

- Supreme.

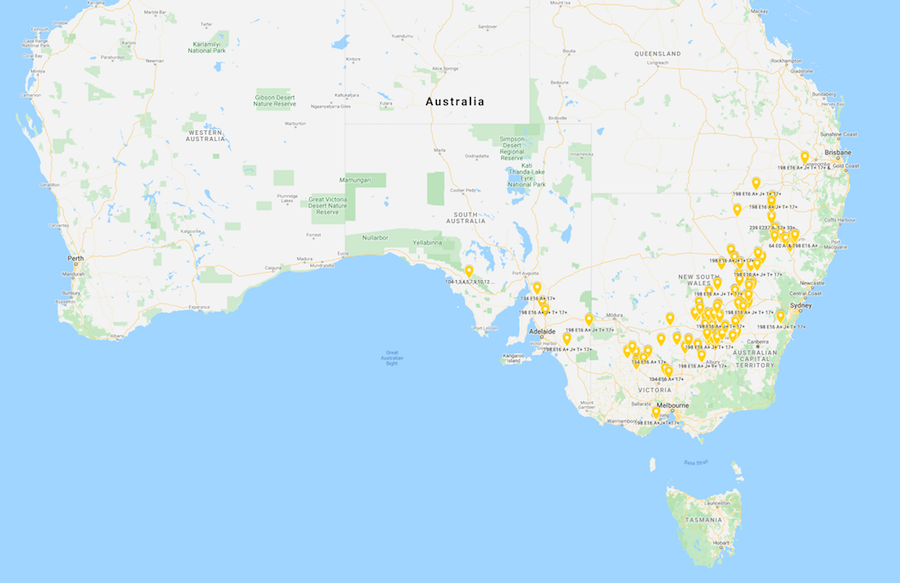

Pathotypes of the wheat Stripe rust pathogen detected in the 2020-21 annual rust survey by researchers at the University of Sydney’s Plant Breeding Institute (up to 23 October 2020). Information from surveys and rust testing is used to make recommendations on the rust responses of current cereal cultivars. Source: University of Sydney

The first detection of virulence for Lr24 was in 2000, 17 years after it was first introduced to cultivars. Like virulence for Yr17, virulence for Lr24 only occurs in eastern Australia. However, unlike virulence for Yr17, virulence for Lr24 has not become dominant in eastern Australia. Only two isolates of the Leaf rust pathogen with virulence for this gene were detected in samples collected in 2020. This means that, unless the pathotypes virulent for this gene increase in frequency, Lr24 should, in many cases, continue to confer resistance to Leaf rust disease.

Keeping a watching brief on where Lr24 virulent pathotypes occur, and their frequency, is important to ensure cultivars with this gene minimise the risk of losses due to Leaf rust.

Sometimes virulence arises, but then seems to disappear. There have been several instances in Australia where virulence has developed for a resistance gene, become common, then disappeared – meaning that a resistance gene that was once of little or no use becomes important again.

A good example of this is the Leaf rust resistance gene Lr23, for which virulence was common in the 1960s until the mid-1980s, but then gradually declined. It has been extremely rare since 2004 and, for the past five years, it has not been detected at all. Cultivars carrying this gene, such as Coolah, EGA Gregory, LRPB Flanker and Sunprime, would have been susceptible to Leaf rust if they were grown in the 1960s to mid-1980s, but they are now resistant.

A word of caution, however, is that just because pathotypes are not detected in our surveys it does not mean they have become extinct. For example, pathotypes of the wheat Stem rust pathogen were detected in the wet summer of 1992-93 in South Australia that had not been found for at least 10 years.

Ongoing monitoring is key

Knowing which rust pathotypes are occurring in different locations and the resistance genes present in cultivars allows recommendations to be made on the performance of cultivars exposed to rust. The factors that determine whether or not virulence for a resistance gene becomes established and common in rust populations are not always obvious, reinforcing the importance of ongoing monitoring of rusts.

Growers can consult the University of Sydney Plant Breeding Institute’s Australian Cereal Rust Survey or current cereal disease guides for each state for the most up-to-date information on varietal responses to rust and other diseases. The rust ratings presented in these guides are based on pathotypes and their frequencies determined through annual surveys at the Plant Breeding Institute.

The success of these surveys depends entirely on the samples received for analysis. As always, growers and agronomists are encouraged to monitor crops closely for rust in the coming season and to forward freshly collected samples, contained in paper only, to:

The Australian Cereal Rust Survey at University of Sydney

Australian Rust Survey

Reply Paid 88076

Narellan NSW 2567

More information: Robert Park, 02 9351 8806, robert.park@sydney.edu.au