The emergence and spread of variants of cereal rust pathogens show very strong parallels with recent experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like COVID-19, the spread of the fungi that cause cereal rust diseases occurs principally via airborne movement. Plants infected with rust generate prodigious numbers of ‘rusty-coloured’ spores that are windborne over vast distances.

Another feature rusts have in common with COVID-19 is the emergence of new variants, known as rust pathotypes, which are analogous to the strains of viral diseases such as COVID-19. As the COVID-19 virus has built up in populations, new strains have emerged via the random process of mutation.

Suppressing the emergence of new viral strains is a strong justification for minimising the amount of virus circulating in populations – more virus, more mutants, more strains and more sickness. Rusts are the same – more rust, more mutants, more pathotypes and more sick crops. Apart from losing yield, allowing rust to develop in crops of susceptible cereal cultivars allows rust pathogens to build up, spread and mutate.

A recent example illustrating the spread and emergence of new pathotypes in cereal rusts is the detection and spread of the stripe rust pathotype 198 E16 A+ J+ T+ 17+, known as pathotype 198. It is likely to have originated from either Europe or South America.

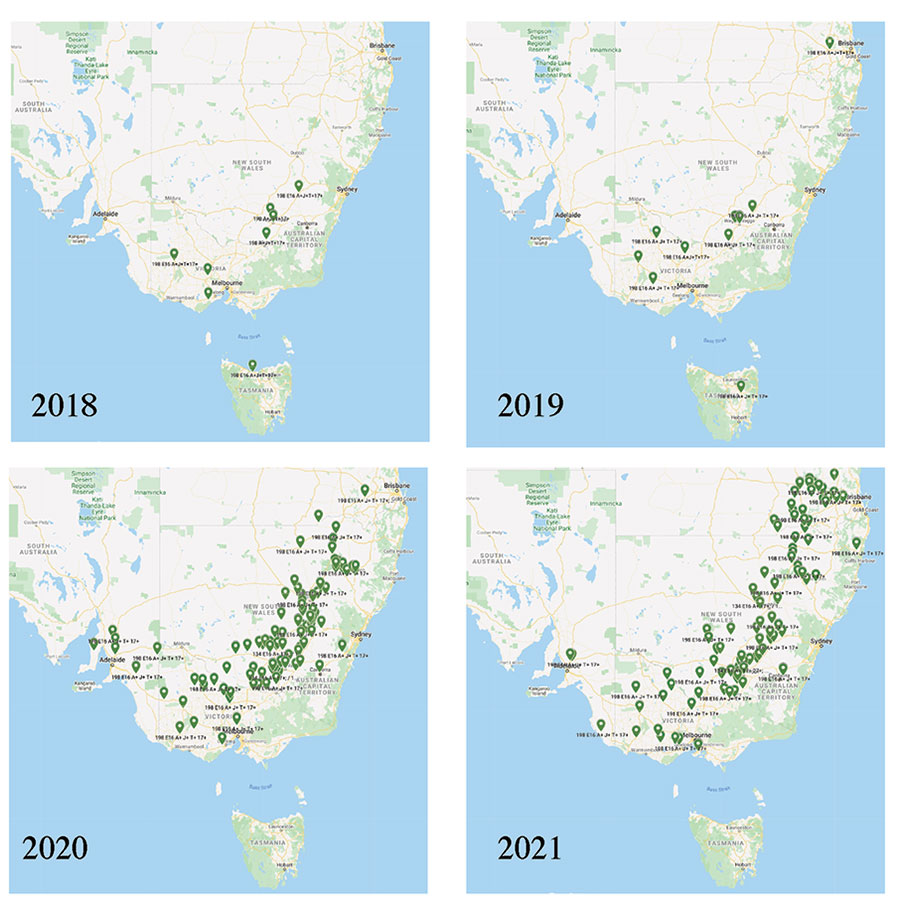

This pathotype was first detected in southern New South Wales in late August 2018 and by 2020 it had spread by wind throughout the eastern wheat growing regions on the mainland and also in Tasmania. Pathotype 198 was also widespread and common across eastern Australia in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pathotype 198 detection and spread

The detection and spread of wheat stripe rust pathotype 198 E16 A+ J+ T+ 17+, known as pathotype 198, in eastern Australia from 2018–21. Each point represents a location from which the pathotype was isolated in each year.

Source: University of Sydney

Given the common occurrence of this rust pathotype during the 2020 and 2021 cereal cropping cycles, it is not surprising that, in 2021, staff at the University of Sydney’s Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) identified two new mutant variant pathotypes derived from pathotype 198. High-throughput greenhouse testing quickly confirmed that these pathotypes do not pose any additional threat to current wheat cultivars. This means that a variety’s disease reaction or rating to 198 is the same for all three variants of the 198 pathogen.

The ability of rust pathogens to spread rapidly over large distances makes them an extremely high biosecurity risk; they are considered to be higher-risk than most other disease-causing pathogens of cereals. This is why they are often referred to as ‘social diseases’.

Not controlling rust in a crop will affect vulnerable neighbouring cereal crops in generating the spores that start new infections. This effect is similar to a person with COVID-19 sneezing in a crowd. Not controlling rust diseases acts as a potential source of new rust pathotypes, affecting the industry as a whole.

The experiences of 2021 and the wet summer suggest there is heightened risk of rust in 2022 crops and underscore the importance of growing rust-resistant cereal varieties whenever possible and avoiding highly susceptible ‘rust suckers’. Due to the incidence of rust in the preceding two seasons and the wet summer, growers and agronomists should also be prepared to manage the heightened risk associated with rust in 2022.

Information on cereal rusts can be found in periodic PBI ‘Cereal Rust Reports’, which include a regularly updated map of rust pathotype distribution.

Please forward freshly collected rust samples, in paper only, to the Australian Cereal Rust Survey at the University of Sydney, Australian Rust Survey, Reply Paid 88076, Narellan, NSW 2567.

More information: Robert Park,