Wheat blast is a fast-acting, severe disease of wheat, caused by the plant fungus Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype Triticum (MoT), which causes bleaching of the heads. It lowers yields and can cause complete yield loss when conditions are favourable to the fungus.

The disease poses an increasing threat to grain growing regions in warm, humid and wet environments.

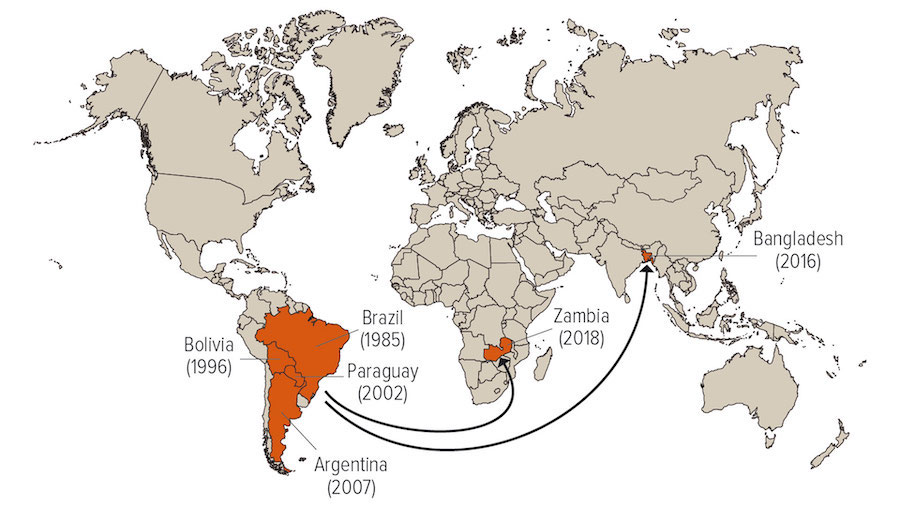

First detected in Brazil in 1985, it spread quickly through South America, infecting about three million hectares of wheat within a decade. In 2016 it arrived in Bangladesh and, by 2020, it was confirmed in Africa, in crops in Zambia.

In both cases, its spread has been attributed to transport through the international wheat trade (see Figure 1). It now threatens wheat production in South-East Asia and southern Africa, with possible further movement to other regions on these two continents.

Spread of wheat blast from South America to South-East Asia and Africa. Source: PK Singh et al 2021*

Impacts and control options

The disease predominantly affects wheat heads that become fully or partially bleached and results in poor-quality, small, shrivelled grains with a reduced test weight.

Maximum yield damage happens when head infection occurs during anthesis or early grain filling and/or when the fungus attacks at the base of the head, thereby restricting the development of the grains and killing the head completely.

Management of wheat blast using fungicides is possible, but they have varying effectiveness. Fortunately, certain seed treatments when used with foliar sprays have had a degree of success overseas.

The search for resistant wheat varieties

The use of resistant genes in breeding programs is considered the best plan of defence in Australia and the most effective means to tackle the wheat blast emerging in South America and Asia.

GRDC invested with the Australian National University (ANU) to assess the performance of some Australian wheat varieties. This work showed that, serendipitously, around a third of current Australian varieties had a level of resistance to wheat blast. While Australian conditions are less conducive to wheat blast, an outbreak would significantly affect wheat yields in affected areas.

Subsequently, a project was launched by Dr Eric Huttner, the research program manager for crops at the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). The project aims to identify and map (at the gene level) new sources of wheat blast resistance and make the material available to breed resistant wheat varieties.

Limited sources of resistance

While genetic-based resistance is considered the best and most environmentally friendly blast management option, sources of resistance in the germplasms screened so far are still limited.

To date, 10 genes and a chromosomal segment have been identified as sources of resistance to wheat blast fungus. These resistance genes could be used in breeding programs to generate a high degree of resistance against wheat blast.

Diagnostics of wheat blast

What does wheat blast look like?

Wheat blast can infect all above-ground parts of the wheat plant. This is often first seen as a scattered patch in the crop. Then, with time, the patches converge and the whole paddock becomes severely damaged. Heads in the infected paddock become a silvery colour while the leaves below may remain green.

Early symptoms include the upper stems and leaves being discoloured, with dark brown, eye-shaped lesions on the leaves. Wheat blast can shrivel and deform the grain in less than a week from the first symptoms.

Wheat head affected by wheat blast. Photo: C. Cruz, Purdue University

What can it be confused with?

Wheat blast sometimes can be wrongly diagnosed because it may look similar to Fusarium head blight (FHB) and spot blotch, caused by Fusarium graminearum and Bipolaris sorokiniana, respectively. The white heads can also be similar to crown rot. It could also be mistaken for drought stress and deficiencies of micronutrients, such as copper.

What should I look for?

Typical eye-shaped lesions on wheat leaf. Photo: C. Cruz, Purdue University

A key visual symptom is patches of bleaching heads in paddocks. Wheat blast infects all above-ground plant parts and causes leaf lesions and head blight. Seeds in infected heads are shrivelled, small and low quality. In severely diseased wheat heads, the seed may be absent. The disease takes hold in warmer regions (18oC to 30oC) with high humidity (over 80 per cent).

More information: Jeff Russell, jeff.russell@dpird.wa.gov.au; ACIAR, 2021. ‘Managing wheat blast in Bangladesh’, Grains Biosecurity wheat blast factsheet.

* Singh PK, et al, 2021. ‘Wheat blast: A disease spreading by intercontinental jumps and its management strategies’. Frontiers in Plant Science, www.frontiersin.org; July 2021, Volume 12, Article 710707.