The old adage that sowing sorghum in spring is a risky business in Central Queensland is being turned on its head. Instead, the practice may have farming system benefits.

Speaking at a GRDC webinar recently, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) senior research agronomist Darren Aisthorpe said there was a belief that soil temperatures needed to be higher than 16°C for success, which meant spring and winter cropping was not considered possible.

Traditionally, Central Queensland’s typical optimum planting period is mid-December through to mid-February. “September and October sowings will usually run into extreme heat during flowering, which also puts the crop in a high-risk position. Later than this window, you run into an increased risk of the fungus Ergot, when minimum temperatures drop below 12°C during flowering,” Mr Aisthorpe said.

To better understand temperature’s effects on sorghum, time-of-sowing (TOS) trials were undertaken. They found that soil temperatures above 12°C had minimal effect on plant emergence and, when compared to a hot planting in January, emergence was slightly better.

“Cold conditions had minimal effect on seedlings. Flowering and grain fill in cooler conditions improved yields and there could be possible farming system benefits,” Mr Aisthorpe said.

Trials

Sown at the Emerald Agriculture College over 2018 and 2019, three TOS dates were evaluated. Both soil and daily air temperatures were monitored and recorded. TOS1 was 25 July, TOS2 was 16 August and TOS3 was 17 January. Flowering for TOS1 was at 84 days; TOS2 was 73 days; and TOS3 was 53 days.

“As expected, emergence was slow for the first sowing date. In warmer optimum conditions, you could expect sorghum crops to be out of the ground within seven to 10 days,” Mr Aisthorpe said.

“So, soil temperature is certainly a bigger driver than air temperature when it comes to inhibiting emergence, but they are linked. However, the work to date seems to indicate that as long as soil temperatures stay above 12°C during the germination to emergence period, the plants will usually make it.

“That said, the time period between sowing date and full emergence can be as much as 20 days or more, depending on soil temperature over that period and the hybrid planted. Once out of the ground, and with conditions remaining cool, the seedlings appear to develop slowly. However, roots continue to develop and sugars are accumulated in shoots, which promotes tillering.”

Mr Aisthorpe said the late-July sowing date (TOS1) performed the best.

Actual plant emergence was mostly on par, particularly for TOS1 and TOS2. However, emergence for TOS3 varied, particularly across the target populations, mainly because of the hot and very dry conditions at planting.

There is a trick to balancing sorghum’s plant population to optimise yield. If a dry season is expected, a low population sorghum is often recommended. However, if the season turns wetter than expected, low populations are likely to produce more tillers, compensating yield. Also, tillers tend to produce slightly smaller grain than the main stem and can increase screening levels. Source: Darren Aisthorpe

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) senior research agronomist Darren Aisthorpe standing in pre-head emergence sorghum. Photo: Melissa Aisthorpe, Cox Inall Communications

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) senior research agronomist Darren Aisthorpe standing in pre-head emergence sorghum. Photo: Melissa Aisthorpe, Cox Inall Communications

Yield balancing act

Because there is a trick to balancing sorghum plant populations to optimise yield, without pushing screenings to unacceptable levels, this was also investigated via the trial.

Mr Aisthorpe said that, typically, high-population sorghum will have far fewer tillers than low-population sorghum. “In a dry season, low-population sorghum is much safer as you can still achieve an economic yield. This is because at low plant populations, more water will be available to the crop later in the season at around flowering and grain filling when it is most needed.”

Tillers tend to produce slightly smaller grain than the main stem and can increase screening levels. This higher level of screenings can push grain quality down.

“In a perfect world, you would plant a crop based on available water, with consistent spacings between the plants which minimised the need for tillers without compromising yield or risk.”

Because it was thought that these ‘typical’ rules might change with spring-sown sorghum, different population densities were tested.

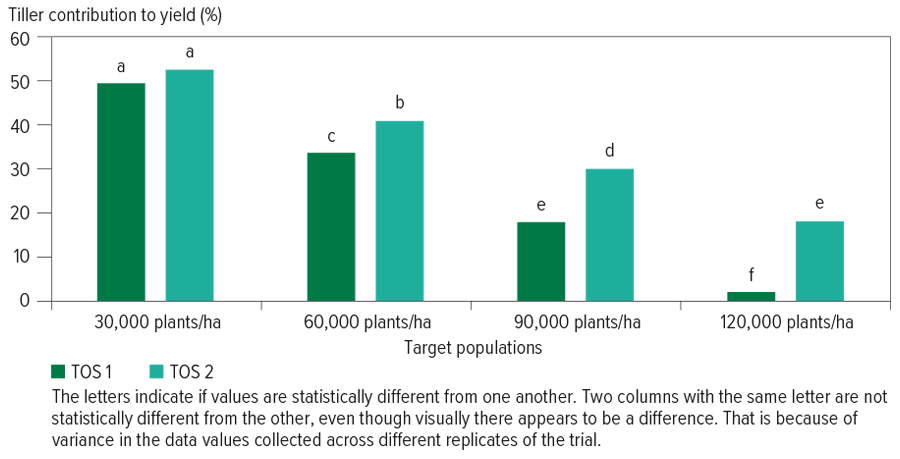

“At 30,000 plants per hectare, nearly 50 per cent of the yield was coming from purely the tillers. As populations increased, contributions from tillers tended to decrease. At 120,000 plants/ha, only 20 per cent of the yield was produced by tillers.

“We found a higher population may be more desirable in winter and spring to compensate emergence losses due to cold soils. We tend to see even-higher tiller counts in winter-sown sorghum, particularly on the lower populations.”

Sowing date also impacted on lodging. “It was most pronounced in the August sowing date, which also happened to experience hotter and drier temperatures at flowering and grain fill than the July planted crop. Therefore, the August sowing date was under greater stress than the first sowing date.”

TOS1 had lower lodging rates for every population range and, interestingly, lodging decreased the higher the population went for TOS1. Yet, for TOS2, the higher the population, the higher the level of lodging, which again is mostly due to stress at flowering and grain fill.

Spring benefits

So far, the research shows that spring-sown sorghum could be beneficial across Central Queensland.

“The benefits stem from being able to sow sorghum in July, giving growers a cropping option in the second half of the year, if moisture was available."

“The added benefit for Central Queensland in particular is that this system will allow growers the option to double-crop back into winter crop the following year, if summer rains are favourable in January to March. This provides a lower-risk double-cropping option, as average rainfall for the period should be sufficient to refill the profile to allow a planting to occur.

“This was something we were able to do for the July and August sowing dates in April 2019, producing a wheat crop which averaged over 3t/ha and provided some interesting preliminary combined water-use efficiency figures for that period.”

The project is a collaboration between the Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation (QAAFI) and the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries.