Growers from the Wallup Ag Group travelled to the Netherlands in late September to hear first-hand about the challenges of farming in a highly regulated country.

Wallup Ag Group comprises growers from Warracknabeal, Dimboola and Horsham in Victoria.

Group secretary Tim Inkster says members applied for a GRDC study tour investment to explore how Dutch growers have adapted their farming systems to remain profitable with fertiliser and pesticide restrictions.

“The Netherlands was chosen because the group’s president, Ceus Wolthuis, grew up on a farm there and moved to the Wimmera in 2001 to expand his business,” Tim says.

“He speaks the language, knows the country and has a lot of contacts, which made this trip a success.”

One of their visits was to a 225-hectare corporate farm where Tanja and Dirk Jan Beuling work in the Drenthe province in the north-eastern part of the Netherlands.

Wallup Ag Group secretary and Victorian grain grower Tim Inkster inspecting feed at a dairy farm in Meedhuizen in the northern part of the Netherlands. The farm has moved to robotics and larger herd size for the business to stay profitable. The farmer has diversified into biomethane used in the gas grid. Photo: Felicity Semmel

Dirk and his partner Tanja spoke of how the farm grows starch potatoes on a two-year rotation; onions on a six-year rotation; seed potatoes on a four-year rotation; and sugar beets, winter barley, summer barley and marigolds. The marigolds are grown to rid the soil of nematodes.

“They provided a fantastic presentation detailing what is involved in securing subsidies from the European Union,” Tim says. “The four areas they need to cover are agriculture, nature, water and climate.”

The farm receives €220/ha (A$360.64) annually, Tim says, and can access €60 to €200/ha extra depending on how well they do. Their total subsidy is about €80,000 a year.

“Much of their frustration is that the rules are trying to preserve nature from the 1950s, but that doesn’t exist anymore because the climate has changed.”

Pictured is Tim Inkster (left), with farmers Tanja and Dirk Jan Beuling, who work on their original family property, now a corporate farm in Drents Groningen Veenkolonien. They produce starch potatoes, sugar beet, summer barley, seed onions and silage. They spoke about the impact of low levels of community trust and tight restrictions on their ability to farm profitably. Photo: Felicity Semmel

Tim says an example of the requirements is that they must nominate when harvest will be completed months in advance, which is difficult to predict. Another example is that 4ha of land must be planted in buffer zones.

Sprayer compliance

Another visit was to machinery dealer and mechanic owner Marcel Peterse in Uithuizen. Marcel said the Dutch government had mandated that sprayers comply with their standards and require testing every three years. He has a special facility for this. Nozzles are allowed a 2.5 per cent variance. Air assist nozzles have reduced drift and helped sprayers reach government standards.

There were no electric tractors in the area, Tim says, but Marcel said it was likely to happen in the future.

“Buses in the cities are electric and hydrogen and seed potato sorting equipment is electrical, but Marcel told us that farmers are reluctant to use more electrical equipment because diesel is more reliable,” he says.

Agrifac factory

A tour of the Agrifac factory was a highlight for Wallup Ag Group members. The company makes seven boomsprays each week, with advanced spray drift reduction technology and minimised track area. The new machines provide better coverage, so less chemical is required. The Dutch government requires very low spray drift and aims to have 50 per cent fewer pesticides used by 2030. Photo: Felicity Semmel

The Wallup Ag Group toured the Agrifac factory at Steenwijk, where Maarten Visscher, sales manager for the Condor sprayers, showed members the state-of-the-art facility. There, a sprayer takes eight days to assemble, with 285 built annually.

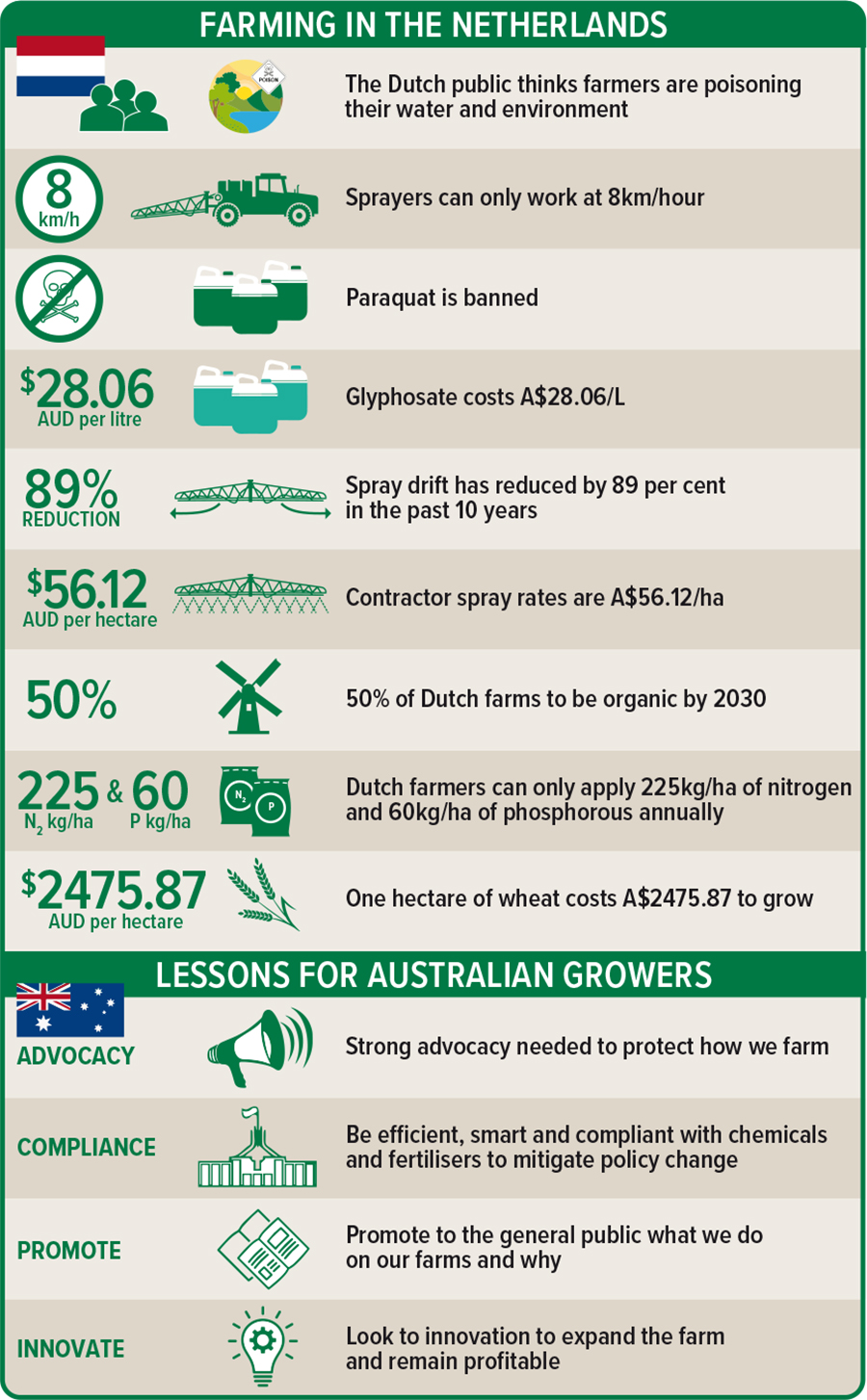

In the Netherlands, Tim says the average amount of land sprayed by contractors is 2.5ha per hour. This is because of high pesticide rates, small paddocks, slower spray speeds (8km/h maximum by law), having to travel to an approved fill point, not being allowed to store chemicals on-farm and restrictions with conditions.

“The Dutch government has given Agrifac the challenge that by 2030 they want 50 per cent less pesticide used and 20 per cent less fertiliser used while aiming for net zero emissions,” he says. “Agrifac sprayers have reduced drift by 97.5 per cent over the past 30 years, and the latest technology is the AirFlowPlus system to create different types of spray drops.”

He says these are more expensive to own and run, but booms can be 30 centimetres above the crop with nozzles spaced at 25cm and at an 80-to-90-degree angle to achieve more even coverage.

Creil ag store

At Creil, the group met Thijs Sijtsma, who owns Profytodsd, a company with 45 employees that advises farmers and provides contracting services.

Thijs said the Dutch government is questioning whether advisers and chemical sellers should be allowed in the same business. France has already disallowed this. The Netherlands may follow.

“Thijs said it takes 12 years for one chemical to be registered, plus three to five years in the Netherlands with more testing,” Tim says. “The chemicals are only valid for 10 to 15 years before undergoing re-evaluation against contemporary criteria, so they are losing active ingredients faster than replacements are developed.”

The group learned that consumers want organic food, but organic milk, for example, is the same price as non-organic milk.

They also discovered it costs €1500 (A$2475) to grow one hectare of wheat. Glyphosate costs €17 (A$28) a litre for 360 strength It is used at 3.5 to 4.0L/ha. Contractor spray rates are €34/ha (A$56.12/ha).

Blitterswijk farm

At Jan Blitterswijk’s farm, Wallup Ag Group members learned he grows potatoes, onions, wheat, carrots and sugar beets. He trades grain, has a contracting business, and created a co-op to sell 20,000 tonnes of potatoes yearly. He has also invested heavily in solar and wind power.

“The farm sits two metres below sea level on reclaimed land and pumps all year round to remove water,” Tim says.

“Wheat is their break crop, but they still aim for 12t/ha.”

Jan told the group it was difficult to find workers as the work is highly specialised.

“Under construction across the farm are wind turbines, a €60 million (A$100 million) project of which Jan is a major investor,” Tim says. “His parting words were the government regulations make everything too hard, and the gap between the rich and poor is growing, which is not good.”

Dogterom flower bulbs

Xander Dogterom took the group on a tour of VOF Dogterom, a farming and flower bulb company based in Oude-Tonge. The company grows potatoes, onions, sugar beets, wheat and tulips.

“They are trying to reduce their emissions before the government makes them and want to be the first tulip producer to be carbon neutral and completely off-grid,” Tim says. “Hydrogen is the option they are exploring. They have as much solar as they can fit, but it is not enough.”

Members learned that tulip bulbs must dry within 24 hours, or fusarium will kill the bulb. Gas is used, and prices are high, so hydrogen is expected to help lower the cost and emissions.

“New technology they are trialling is a heat pump to store warm air 200m below-ground,” Tim says. “By 2030, the family plans to use robotics to assist with irrigation, weed control and a mobile solar farm. They are also looking at a robotic machine that detects and removes plants with disease.”

Netherlands’s largest farm

The group visited the largest farm in the Netherlands – called Koninklijke Maatschap de Wilhelminapolder – based north of the city of Goes, Zeeland.

Tim says it is a co-op of 400 owners across 2000ha farming potatoes, onions, wheat, barley, faba beans and lucerne. Sugar beets were dropped from the rotation because of compaction issues.

“They have 15 full-time workers,” he says. “They also farm shellfish in plots in the ocean outside the dyke.”

Study findings

The Wallup Ag Group’s findings were that farmers in the Netherlands were highly regulated and had to follow European Union rules and their own government’s rules.

Tim says the land is below sea level, so farmers constantly remove water from their paddocks to the sea via a canal system.

“This water is used by the public for drinking, and it is monitored for fertiliser and chemical contamination,” he says. “Although Australian farmers are in a different environment, we don’t think we will be immune from similar restrictions in the future.”

Another discovery was that Dutch farmers can only apply 225 kilograms/ha of nitrogen and 60kg/ha of phosphorus annually.

Tim says chemicals are reviewed and can be removed from the system overnight.

“The whole focus of farmers in the Netherlands is making sure they comply; otherwise, the penalties are significant,” he says. “Ten years ago, there were 160 crop protection products; now, there are only 60.”

Seed potatoes are grown in the northern Netherlands and exported worldwide. The group visited the Family Klein, Uithuizermeeden. The potatoes are put into storage crates using automation, sorted in winter, and mostly sold in hessian bags for export. Photo: Felicity Semmel

He says glyphosate use is limited but not yet banned, and insecticide applications are limited to two a year. Paraquat has been banned.

"They cannot use seed treatments, and triazole fungicides will be banned in two years,” he says. “The replacement fungicides are more expensive.”

Crop rotations have had to change, Tim says, because of the restrictions.

“They are looking at nitrogen-fixing bacteria to add to sprays and cover crops to fix nitrogen so they can reduce the amount of inorganic nitrogen applied,” he says.

“Each farm relies heavily on professional advisers to ensure what they are doing and the products they use are legal and achieving the best results possible.”

Spray drift

During the past 10 years, Tim says, spray drift in the Netherlands has reduced by 89 per cent.

“Farmers cannot spray unless everything on the label is adhered to (as per Australia) but their sprayers are monitored by the government with pressure loggers to see that the job matches the chemical used and is compliant,” he says.

“Industry has worked hard to meet these demands, and sprayer set up, nozzle selection, air induction, litres-per-hectare rate and spray additives have all helped Dutch farmers remain compliant.”

The government has mandated all sprayers to be tested every three years, he says, to ensure they are meeting the standards set.

“Farmers are also required to plant buffer zones around their paddocks; the size depends on the time of year, the crop grown, and the chemicals used. Four per cent of their land must be for the environment," he says.

“Farmers cannot pump water out of the canals and drains around their paddocks for spraying, so most of their time is spent travelling to a water fill point. New sprayers are fitted with technology enabling the machine to be cleaned in the paddock, further reducing any risk of contamination between jobs or from travelling.”

Tim says the group looked at one organic farm, which had many more implements designed to manage weeds.

“The labour input is much higher than conventional farms with many more passes, but also using people to pull out weeds,” he says. “The government wants 50 per cent of Dutch farms to be organic by 2030, but nobody knows how this will be possible.”

He says the public has a very negative view of Dutch farmers and thinks they are poisoning their water and environment.

“It is difficult for Dutch farmers to change this perception and stand up for farming and their profitability,” he says. “Sixty per cent of land is used for agriculture but only one per cent of the population works in agriculture.”

Tim says the Dutch government is considering lowering emissions and is not worried about how that affects farmers because it has the public’s backing.

“The Dutch government is also acquiring farmland to return it to nature,” he says. “These areas may not seem large, but 20ha is a significant amount of land that instantly makes farms unviable overnight.”

He says there is no other land to purchase, so people are forced out of agriculture or into another country.

“Carbon emissions are being audited as part of their compliance to receive subsidies, and this is becoming more onerous yearly,” he says. Farmers can opt out of subsidies, but why would they restrict their income if they must comply with 90 per cent of the rules anyway?”

He says public transport, such as buses, are electric and hydrogen powered. Electric tractors were not used, but they expect that will change soon.

Tim says the farms visited were proactive in growing as much produce as possible, but they were also searching for new sources of income and compliance with the government.

Wallup Ag Group members Mark Gaulke, Tim Inkster and Russell Barber with Dutch farmer Maurits te Braake (third from left) at his dairy farm, which has expanded into methane production. Ninety tonnes of manure from the farm and organic waste from other industries are pumped into digestors (pictured) and stored. The farmer pays for the methane to travel to the grid, and the liquid product is spread onto paddocks. The plant cost €4 million without subsidies. While the gas remains in the Netherlands, the green certificates are sold to England. Photo: Felicity Semmel

“Solar panels and wind turbines cover the country. Some farmers were investing in these as another source of income. The farmers put away money to upgrade or decommission these technologies.”

He says biogas plants are also being built, and ways to save energy costs are at the forefront of each business with heat pumps and storage, another new technology.

“Larger farms have bought out smaller farms, so they are in a more secure financial position. The gap between the rich and poor is growing, something the Dutch government seems fine with.”

Lessons for Australia

Tim says the group learned that we need strong advocacy to protect how we farm in Australia.

“We need to be proactive regarding chemical and fertiliser use and be as efficient, smart and compliant as possible to mitigate policy changes,” he says

“We must also be proactive in promoting what we do and keep the public well informed about what we do, why and how, and – if possible – look to innovation to expand our enterprises to remain profitable.”

He says Dutch farmers are constantly evolving to remain profitable.

“As grain growers, we need to improve our sprayer set-up and spray drift management,” he says. “Technology is addressing this as it becomes more affordable, and growers look to invest in new sprayers.”

More information: Tim Inkster, timinkster@hotmail.com