Knowing when to seal silos is a simple yet often misunderstood concept, possibly stemming from the thought that sealing silos will keep weevils out. But that is not what a silo seal is for.

The aim and sole purpose of sealable silos is to ensure successful fumigations to control insects. There is no other purpose or time a silo should be sealed. In fact, sealing a silo for long periods increases the risk of grain degradation and can cause silo damage.

Silo designs have progressed over the years and the introduction of the Australian Standard AS 2628-2010 sets a benchmark for gas-tight, sealable silos. Successful insect control is contingent on meeting these standards. This point can’t be emphasised enough. A leaking ute tyre is quickly fixed, as should a silo that doesn’t meet these standards!

What is sealed?

Gas-tight-sealed silos meeting the Australian Standard (AS 2628-2010) will pass a five-minute, half-life pressure test when new. Research indicates a three-minute, half-life pressure test is sufficient for existing silos. This test is a reliable method to ensure the silo will hold fumigation gas at an adequate concentration and time to control insects at all life stages – egg, larvae, pupae and adult.

The pressure test involves 250 pascals (kPa) of pressure, which equates to 0.036 pounds per square inch – well below the pressures used in tyres on vehicles and farm machinery.

The Australian Standard (AS 2628-2010) gives buyers of new silos confidence they will get what they are paying for. In its absence, the interpretation of ‘sealed’ can vastly differ from one person to another.

When ordering silos, buyers should request the manufacture guarantee and include reference to the Australian standard AS 2628-2010 on the invoice and insist a pressure test be demonstrated on delivery or construction.

Why the pressure on sealing?

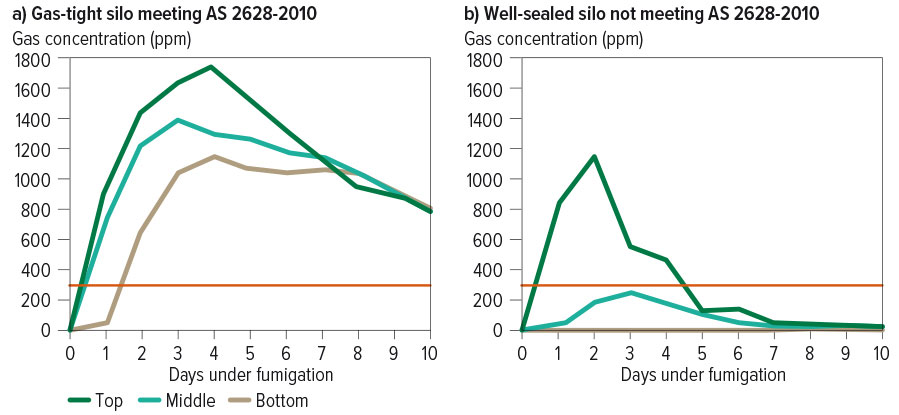

Research by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries examined the difference in fumigation performance of two identical silos (Figure 1a verses Figure 1b, below), with the exception that one had slightly compromised seals (Figure 1b).

The first silo passed a three-minute, half-life pressure test (Figure 1a), while the second could be pressurised but was unable to meet the three-minute, half-life pressure level mark to pass the test (Figure 1b). Essentially, the first silo was gas-tight sealed, while the second, although appearing to be very well sealed, did not pass the Australian standard pressure test.

The fumigation results contrasted in Figures 1a and 1b illustrate the difference in gas concentration between the two silos.

The silo passing the pressure test (Figure 1a) maintained over 300 parts per million (ppm) of phosphine in all areas of the silo for the required seven days to provide effective control of all insect life stages, including eggs and pupae. The second silo (Figure 1b), while appearing well-sealed, failed to maintain 300ppm for seven days and was unable to reach 300ppm in the middle or bottom of the silo.

Many insects would have survived the fumigation in the second silo and, more alarmingly, fumigations in silos like this add to the growing issue of pests becoming resistant to fumigation gases.

Why not leave silos sealed?

Apart from sealing silos for the fumigation periods as directed by the label, silos should be left unsealed to allow air movement.

There are two main risks with sealing silos for extended periods of time: structural damage and grain degradation. Structural damage or deterioration of seals can occur if the weather changes suddenly and the air inside the silo expands or, more so, when it contracts during rapid cooling.

As the air temperature and, therefore, the pressure changes inside a gas-tight-sealed silo, the pressure relief valve is needed to let air in or out. During rapid changes, the volume of air to exchange can be greater than what the pressure relief valve can let through, which causes increases or decreases in air pressure to potentially damaging levels inside the silo.

The most obvious way to avoid the chance of this happening is to not leave the silo sealed unless it is under fumigation. The issue is exacerbated when silos are not full of grain, as this means there is a greater volume of air in the silo that will expand or contract.

If partially full silos do have to be sealed for fumigation, a close eye should be kept on the weather forecast for rapid changes such as a drop in temperature or a storm on a hot day.

The best protection for silos is to ensure the pressure relief valve and any air flow piping to the head space is of adequate size for the silo. For large (more than 750-tonne) flat-bottom silos, two or more pressure relief valves are typically required.

Grain degradation can occur if silos are sealed soon after filling, locking in warm harvest grain with varying moisture contents.

The warm air in the head space can lead to condensation forming and dripping down the walls onto the grain, causing mould. To avoid this issue, leave the silo open to vent and breathe, without letting rain in. A sealable vent or, alternatively, propping the lid partially open can achieve this.

Ideally, grain would be cooled with aeration fans to create uniform moisture and temperature conditions that will help prevent mould and insects. This approach also extends seed viability stored in the silo.

More information: visit the Stored Grain website; 1800 WEEVIL (1800 933 845).

Figure 1: Difference in gas concentration between a gas-tight silo that meets AS 2628-2010 and one that does not.