Key points

- Intensive canola/wheat crop rotations fertilised with high levels of nitrogen produced the highest gross margins in wet seasons but produced lower investment returns in dry seasons

- Nitrogen supply underpins most of the profitability differences between the different cropping systems

- Successful integration of grain legumes on the farm involves thinking about the effects on labour, machinery availability, storage and marketing

Researchers have confirmed which cropping rotations were the most profitable and the least risky at two locations in southern New South Wales from 2018 to 2022.

For five years, CSIRO Agriculture and Food chief research scientist Dr John Kirkegaard and his colleagues have partnered with researchers at the NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI), growers and agronomists to explore how rainfall can be converted more efficiently into profit across entire crop sequences.

Also monitored were the effects on soil fertility, weeds, diseases and costs.

In 2017, experimental sites were established at Wagga Wagga (core), Greenethorpe, Condobolin and Urana.

The research team, with GRDC, CSIRO and NSW DPI co-investment, explored:

- crop diversity by introducing more legumes into the farming systems;

- the effects of nitrogen based on conservative and optimistic outlooks;

- early versus timely sowing; and

- crop grazing versus no crop grazing.

When the project was set up in 2017, growers and advisers told Dr Kirkegaard that a rotation of barley/canola/wheat was the typical ‘baseline’ farming system.

“The growers and advisers wanted to see a crop sequence of barley/canola/wheat compared with a farming system that incorporated different legumes followed by canola and then wheat to see how profit varied over time,” he says.

“With nitrogen, we looked at a conservative strategy that assumed the season would not finish well (decile 2) versus an optimistic approach (decile 7) that assumed every season would finish well.

“We have also been pushing the sowing date of our crops earlier to March and early April – and comparing that with timely May sowing.

“Another treatment of interest has been comparing grazed crops with ungrazed crops.”

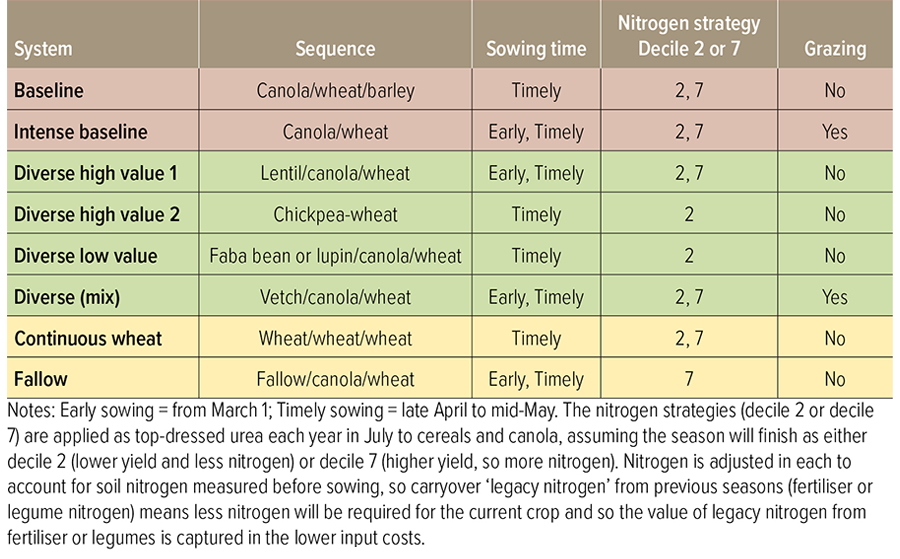

He says the baseline farming system was barley/canola/wheat with conservative decile 2 nitrogen inputs and timely May sowing (Table 1).

Table 1: Farming systems common to most of the four sites, including different crop sequences, time of sowing and nitrogen strategies. Early sown (March) treatments included winter-grazed crops at Wagga Wagga and Greenethorpe, NSW.

Source: John Kirkegaard, CSIRO; Mathew Dunn, NSW DPI; Tony Swan, CSIRO; Jeremy Whish, CSIRO; Russell Pumpa, NSW DPI and Kelly Fiske, NSW DPI.

Seasons 2018 and 2019 were dry (decile 1 to 2) across all sites, while 2020, 2021 and 2022 were wet.

In the first three-year phase of the project, the research outcomes were heavily influenced by the dry 2018 and 2019 seasons.

The results showed:

- at all sites, there were farming systems that:

- were $200 to 300 per hectare more profitable than the baseline;

- were less risky;

- had stable or declining weed and disease burdens;

- had lower average input costs;

- were robust in the long term compared to the cereal/canola system.

- in mixed (grazing crop) systems, the most profitable alternatives were early sown grazed crops (wheat/canola) with a higher nitrogen fertiliser strategy (decile 7) or in sequence with a legume (vetch);

- in crop-only systems, timely sown, diverse sequences with legumes and a more conservative (decile 2) nitrogen strategy were the most profitable.

After a wet 2022, Dr Kirkegaard says growers, scientists and agronomists were interested to see whether three wet seasons from 2020 to 2022 had changed these outcomes.

“Wet seasons provide opportunities to lift grain yield and profitability and to capitalise on higher nitrogen strategies and earlier-sown crops,” he says.

“However, they can also increase input costs for fungicide and fertiliser and, in very wet years, increase the risks of yield penalties due to higher disease levels, increased lodging, reduced grain quality and reduced operation timeliness.”

Accordingly, the researchers compared the gross margin and risk of various systems over five seasons to determine how wet seasons influenced profit and risk.

Also explored was the separate performance of the dry (2018, 2019) and wet (2020, 2021, 2022) seasons to demonstrate how seasonal conditions influence gross margin, variability and risk.

When writing, Dr Kirkegaard could only discuss the grain-only systems at Wagga Wagga (Table 3) and Urana (Table 4) provided by Mat Dunn from NSW DPI at Wagga Wagga because results from Greenethorpe and Condobolin were yet to be analysed.

Wagga Wagga site

Average gross margin

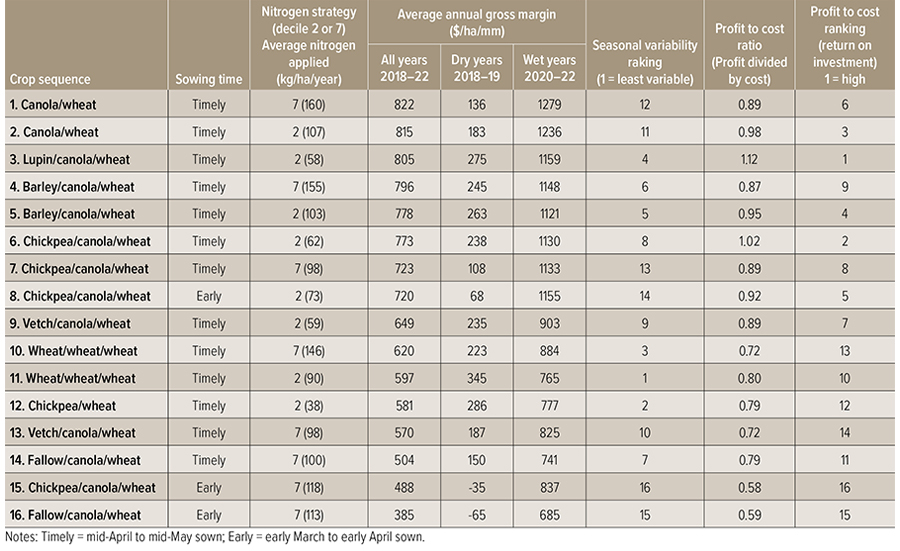

Dr Kirkegaard says the highest gross margins in grain-only systems at Wagga Wagga, averaged across five seasons, were the intensive canola/wheat systems with a decile 7 and decile 2 nitrogen strategy (Table 2).

“The diverse lupin/canola/wheat system with decile 2 nitrogen strategy was the third-most-profitable farming system and more profitable than the barley/canola/wheat baseline systems.

“The diverse system with chickpeas and low nitrogen fertiliser was marginally less profitable than the baseline, while all other systems were more than $50/ha/year less profitable than the baseline.

“The least profitable systems involved either fallow (16, 14 in Table 2), early sown systems with legumes and/or high nitrogen (15), or the continuous cereals (10, 11).”

Variability and risk

Despite the intensive canola/wheat systems generating higher average gross margins overall, Dr Kirkegaard says this was driven by better performance in wet seasons (Table 2).

“Intensive canola/wheat systems performed poorly in the dry seasons,” he said.

“By contrast, the diverse lupin/canola/wheat system with low nitrogen (3) had among the highest gross margins in the dry seasons. It was the third-highest system in the wet seasons.”

He says this lower variability was accompanied by the highest return on investment and the lowest risk.

“While continuous cereals (10, 11) and the chickpea/wheat systems (12) performed well in dry seasons and had more stable gross margins, their poor performance in wet seasons and low return on investment made them less attractive.”

Overall, Dr Kirkegaard says higher gross margins in wet years strongly influenced average gross margins.

“Accordingly, the wet years favour systems with a higher canola intensity (1, 2),” he says.

“However, the higher nitrogen needed in canola/wheat systems (decile 7) means they are only marginally more profitable and have a higher profit/cost ratio than the decile 2 strategies.

“Diverse systems with either lupins (3) or chickpeas (6) and grown with a low nitrogen strategy (decile 2) remain as profitable or more profitable than the baseline system of barley/canola/wheat (4, 5).

“These diverse systems combine high overall profitability with a higher return on investment, more stable gross margins and lower risk.”

Table 2. Average gross margins ($/ha/year) for the grain-only systems at Wagga Wagga, NSW.

Notes: Timely = mid-April to mid-May sown; Early = early March to early April sown. Source: Mathew Dunn, Russell Pumpa and Kelly Fiske, NSW DPI; John Kirkegaard, Tony Swan, Jeremy Whish, CSIRO.

Urana site

Average gross margin

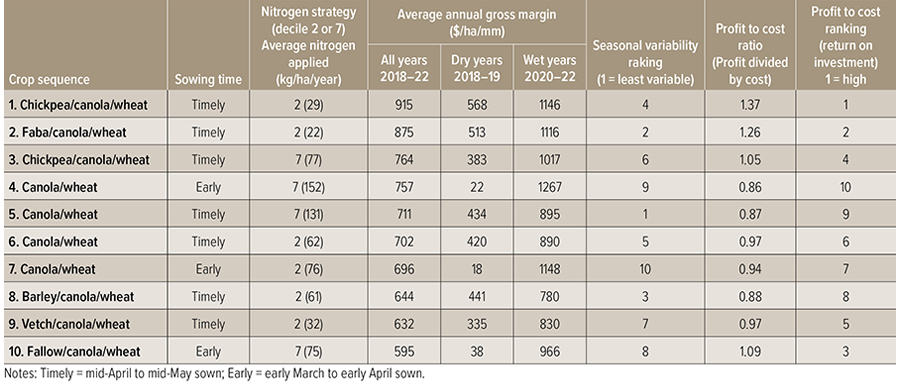

Dr Kirkegaard says the most profitable grain-only systems at Urana were the diverse legume/canola/wheat rotations involving chickpeas or faba beans with lower (decile 2) nitrogen inputs (Table 3, systems 1, 2, 3).

“These were $100 to $200/ha/year more profitable than the intense canola/wheat systems (4 to 7) or the baseline barley/canola/wheat system (8),” he says.

“Within the cereal/canola systems, the early sown canola/wheat system with higher nitrogen inputs was the most profitable and about $100/ha/year more profitable than the baseline system.

“The least profitable systems at Urana were those involving fallow or vetch (9, 10).”

He says the difference with the Wagga Wagga results was the relatively low profitability of the baseline system at Urana and the exceptional performance of the diverse systems with faba beans or chickpeas with lower (decile 2) nitrogen inputs.

Variability and risk

Dr Kirkegaard says the high profitability of the diverse systems involving chickpeas and faba beans resulted from their excellent performance across dry and wet seasons (Table 3).

“In contrast, the intensive canola/wheat systems sown early had very low profitability in dry seasons despite being among the highest gross margins in wet seasons, especially with high nitrogen inputs,” he says.

“The diverse systems with low nitrogen inputs also had a higher return on investment (1.05 to 1.37) – well above that of the intense canola/wheat systems or the baseline system (0.87 to 0.97).

“The fallow/canola/wheat system (10) had a relatively high return on investment (1.09) and performed well in the wet years, presumably due to fewer inputs and higher-yielding wheat and canola crops.

“But the lack of income every third year and the limited value of stored water in the wet seasons generated low overall gross margins.”

For Urana, Dr Kirkegaard says diverse systems with legumes (faba beans or chickpeas) combine high overall and stable gross margins over different seasonal conditions and a high return on investment (lower risk). This was despite a run of wet years and low chickpea yields in the wet and cold 2022 (1.2t/ha).

“Intensive canola/wheat systems also outperformed the baseline barley/canola/wheat, presumably due to greater frequency of the more-profitable canola crops during recent wet seasons, which responded to earlier sowing and high nitrogen inputs.”

Table 3. Average gross margins ($/ha/year) for the grain-only systems at Urana, NSW.

Source: Mathew Dunn, Russell Pumpa and Kelly Fiske, NSW DPI; John Kirkegaard, Tony Swan, Jeremy Whish, CSIRO.

Regarding the consequences of three consecutive wet seasons, Dr Kirkegaard says both sites have diverse systems with low nitrogen strategies that deliver either the highest or among the highest gross margin with lower variability and high investment returns.

“The more-intense canola/wheat systems were more profitable than the baseline systems, but with greater variability and lower returns at Wagga Wagga and Urana,” he says.

“Diverse systems involving legumes with lower nitrogen inputs remain either the most profitable (Urana) or among the most profitable (Wagga Wagga) farming systems, with the highest return on investment and low variability of gross margin.

“Intense canola/wheat systems with high nitrogen inputs improved in their economic performance compared to the baseline systems due to the higher gross margins from canola in wet seasons.”

Nitrogen supply

NSW DPI research officer Mat Dunn says nitrogen is a big driver of yield potential in wet seasons when water is not limiting, especially for canola.

By way of example, at Wagga Wagga, he says, canola yields increased by 0.4t/ha on average in decile 7 nitrogen baseline (barley/canola/wheat) and intense baseline (canola/wheat) systems compared to equivalent decile 2 systems. Wheat was less nitrogen responsive.

NSW Department of Primary Industries research agronomist Mat Dunn checks a companion crop plot at the farming systems core site at Wagga Wagga, NSW. Mr Dunn says the soil pH at the Wagga Wagga, NSW trial site was far lower than that at the Urana, NSW, farming systems site. Soil pH at the Wagga Wagga, NSW, site was so low, he says, it affected legume growth. Photo: Nicole Baxter

“In very wet years such as 2022, the additional costs of multiple fungicide sprays and additional nitrogen, and yield reductions related to higher disease or lodging can diminish the responsiveness to nitrogen,” he says.

“Grain legumes do not require nitrogen, which is a cost saving and can reduce the amount of nitrogen required on subsequent crops – also a cost saving.”

He points to Tables 2 and 3, which show that the average amount of nitrogen supplied to the diverse and low-nitrogen legume/canola/wheat system was 60kg/ha at Wagga and 25kg/ha at Urana a year, respectively.

By contrast, he says, the baseline barley/canola/wheat needed 103kg/ha/year at Wagga and 61kg/ha at Urana.

“The reduced nitrogen required, which equated to about 40kg/ha/year, represents a considerable cost saving, especially when nitrogen prices are high,” he says.

“At Wagga Wagga, 50kg/ha more nitrogen fertiliser was applied annually above what was supplied to the high nitrogen (decile 7) baseline treatment. This increased gross margins above the decile 2 baseline system only marginally (by $18/ha/year), but it remained less profitable than the diverse lower nitrogen system and had a much lower return on investment.”

Canola profitable

Mr Dunn says canola following legumes in diverse sequences had significant grain yield and gross margin increases compared to those in the baseline systems at Urana, which generated further increases in the gross margins. This increase in canola grain yields was not observed at Wagga Wagga.

He says the Wagga Wagga site has a more acidic, lighter textured soil with a lower organic carbon level in the top 10 centimetres than the Urana site.

“The combination of soil chemical, texture and structural properties at Urana may have favoured longer or more rapid nitrogen mineralisation,” he says.

“On average, we found double the amount of soil mineral nitrogen following legumes and before sowing the following canola crop at Urana compared with Wagga Wagga.

“The nitrogen available at Urana was 73kg/ha, while the nitrogen available at Wagga Wagga was 36kg/ha.

“The extra soil nitrogen available before top-dressing in July combined with a likely higher rate of in-crop mineralisation may have contributed to the significant canola grain yield increases found at Urana, but not Wagga Wagga.”

Reduced nitrogen costs

Mr Dunn says cost savings through reduced nitrogen costs and an increased gross margin from higher yield outweighed the lower gross margins of the legume crops, despite higher fungicide costs and some yield reduction in wet years.

“Notwithstanding the poor 2022 chickpea yields caused by prolonged cold and wet conditions, the grain yields and gross margins of legumes in the wet seasons have been reasonable,” he says.

“Results showed the chickpea yield, on average, was about 3t/ha at Wagga Wagga and Urana ($800 to $1000/ha gross margin), while lupins yielded 3.8t/ha ($670/ha) at Wagga Wagga and faba beans yielded 5.9t/ha ($1200/ha) at Urana.”

Although grain legumes do not always produce the highest gross margin in specific seasons, he says, their returns have been reasonable and sufficient with legacy effects making them a profitable inclusion in the system.

Business considerations

Dr Kirkegaard says the results from both sites demonstrate that systems with relatively small differences in average annual gross margin across five years can be profitable but may contrast in performance in different seasons (wet, dry) and have different risk levels.

“Different systems may suit specific businesses depending on a range of factors other than agronomic management and must be considered when making decisions to integrate grain legumes into the business,” he says.

“For example, to ensure the best outcome from grain legumes, some form of on-farm storage is likely required.

“Other considerations include the capacity to handle inoculation in a timely and effective manner and proactive fungicide application in wet seasons.

“Accordingly, labour peaks and demand on machinery must be considered.”

Dr Kirkegaard says enterprises with significant areas of legume-based pastures might find that these can supply organic nitrogen while also assisting disease and weed management.

“Legume-based pastures are suited to phased rotation with more intensive cereal/canola systems,” he says.

“The choice of legume is important based on those best adapted to specific paddocks.

“Nevertheless, preliminary data provided by Mat Dunn and the NSW DPI team from these experiments at Wagga Wagga and Urana demonstrate the value of fully assessing grain legumes across different systems beyond their performance in individual years.

“Much of the benefit of grain legumes derives from their legacy effects, input savings and more-even performance across seasons.

“These are difficult to assess without long-term side-by-side comparisons and supporting data to understand the mechanisms behind the responses.”

Acknowledgements

Dr Kirkegaard and Mr Dunn acknowledge input from GRDC, NSW DPI, Warakirri Cropping, Graeme Sandral, Chris Baker (Baker Ag Advantage), Tim Condon (Delta Agribusiness), Greg Condon (Grassroots Agronomy), James Madden (Lockhart), Heidi Gooden (Delta Agribusiness), Peter Watts (Elders), Rod Kershaw (Iandra Castle), John Stevenson (Warakirri Cropping) and John Francis (Agrista).

More information: John Kirkegaard, john.kirkegaard@csiro.au, @AgroJAK (Twitter); Mat Dunn, mathew.dunn@dpi.nsw.gov.au, @MathewDunn19 (Twitter)

Watch

GRDC Grains Research Update – Wagga Wagga, Farming systems – profit over time and risk