Key points

- A legume phase offers the opportunity to fulfil the yield potential of subsequent crops delivered by soil amelioration, improved agronomy and genetic advances

- At the GRDC-supported Agronomy Australia Conference in Albany in October, James Easton, a senior agronomist with CSBP, spoke about legumes’ role in improving cropping returns in Western Australia

- CSBP has run a series of trials showing the potential for boosting cropping returns in high-yield-potential environments by including legumes

A legume phase offers growers the opportunity to capitalise on the higher yield potential of subsequent crops delivered by soil amelioration investments, improved agronomic practices or advances in genetics, trials show.

At the GRDC-supported Agronomy Australia Conference in Albany in October, James Easton, a senior agronomist with CSBP, spoke about the company’s trials comparing cereals and canola sown into a legume stubble versus sowing back into a cereal or canola stubble.

Different rates of nitrogen were also applied to further measure what benefits legumes could bring to the following crops.

Mr Easton said that collectively the trials showed clear potential for boosting returns in high-yielding environments by including legumes in the rotation.

Trial details

The trials were run at four sites across the central grainbelt with variations on legumes, following crops and nitrogen rates. Flexi-N, a liquid fertiliser, was the nitrogen source, with rates applied to the nearest 10 litres per hectare. Soil organic carbon content was used as an estimate of soil nitrogen reserves. It is used in WA with typical carbon:nitrogen ratios between 12 and 14. Soil pH varied across the sites.

Table 1: Soil pH (measured in CaCl2) at each of the experimental sites.

Depth (cm) | Dandaragan | Meckering | Toodyay | Bruce Rock |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0–10 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 6.5 |

10–20 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

20–30 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 4.7 |

Source: James Easton

Dandaragan

Soil: deep yellow loamy sand with a good history of lime applications and recent deep ripping.

Nitrogen: low organic reserves (organic carbon 0.4 per cent).

Cropping: continuously cropped for many years without a legume.

Experiment

In 2021, lupins and canola were planted. The canola was fertilised with 169 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare. In 2022, wheat was grown with three rates of nitrogen – none, 59kg/ha and 118kg/ha. In 2023, barley was grown with the three rates of nitrogen in 2022 reapplied to the same plots – none, 59kg/ha and 118kg/ha.

Results

There were similar responses to high nitrogen rates (118kg N/ha) in wheat after lupins as in wheat after canola. However, at all three nitrogen rates, yields were 1.5t/ha higher after lupins. With 118kg N/ha applied, grain protein after lupins was 9.1 per cent compared with 8.4 per cent after canola. This lifted the grain into a higher-paying segregation (ASW9). Mr Easton said the site had high yield potential, but soil nitrogen reserves were low.

It is unlikely that higher nitrogen rates would have bridged the yield gap, plus this is risky and expensive.

“There were legacy benefits from growing barley in the lupins (yields were 0.3 t/ha higher than after canola two years earlier), which showed the need to consider these potential benefits of increased yields two years on when making decisions on paddock rotations.

“A productive legume phase may be required to capitalise on the good seasons, especially if soil nitrogen reserves are low and soil amelioration has increased the yield potential.”

The Meckering site’s canola crop in 2023 after a previous lupin crop.

Meckering

Soil: deep yellow loamy sand with a good history of lime applications and recent deep ripping.

Nitrogen: low organic reserves (organic carbon 0.6 per cent).

Cropping: continuously cropped for many years with the last lupin crop in 2019.

Experiment

In 2022, lupins and wheat were planted. The wheat was fertilised with 84kg N/ha. In 2023, canola was grown with four rates of nitrogen – none, 30kg/ha, 59kg/ha and 118kg/ha.

Results

With high nitrogen rates (118kg N/ha), canola yield after lupins was 1.1t/ha higher than canola after wheat. Like Dandaragan, the site had high yield potential, but soil nitrogen reserves were low.

The Meckering site’s canola crop in 2023 after a previous lupin crop. Photo: James Easton

The Meckering site’s canola crop in 2023 after a previous wheat crop. Photo: James Easton

Bruce Rock

Soil: deep yellow loamy sand with a good history of lime applications and deep ripping.

Nitrogen: reasonable organic nitrogen reserves (organic carbon 1.1 per cent).

Cropping: lupins were planted in 2020.

Experiment

In 2022, lupins and wheat were grown. The wheat was fertilised with 59kg N/ha. In 2023, wheat was grown with four rates of nitrogen – none, 30kg/ha, 59kg/ha and 118kg/ha.

Results

Higher nitrogen rates on the wheat-on-wheat crop produced comparable yields to wheat after lupins. However, higher protein levels after the lupins indicate that this rotation strategy could have produced higher yields with lower risk, had better finishing rains made the yield potential higher.

Toodyay

Soil: red brown loamy clay.

Nitrogen: reasonable organic nitrogen reserves (organic carbon 1.1 per cent).

Cropping: continuously cropped for many years without a legume.

Experiment

In 2022, faba beans and wheat were grown. The wheat was fertilised with 93kg N/ha. In 2023, canola was grown with four rates of nitrogen – none, 51kg/ha, 101kg/ha and 198kg/ha.

Figure 1: Gross margin analysis to the end of 2023 from the four experiments.

Source: supplied by James Easton

Results

Higher nitrogen rates on the canola-on-wheat crop produced comparable yields to canola after faba beans.

However, lower canola oil after faba beans suggests that the nitrogen benefit from the legumes was limited by yield potential due to a dry finish to the season. Therefore, the nitrogen benefit should carry through to future crops.

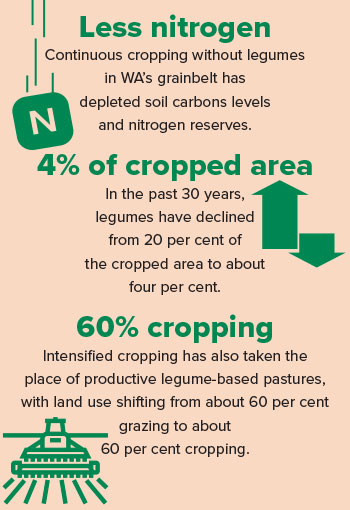

Changing landscape

Source: ABARES

Profitability

Mr Easton said the results were promising, especially when the rotational benefits from growing legumes were considered rather than just single-year gross margins.

“Profitability is driven by lowering the cost per unit of production. At Dandaragan, the 40 per cent higher wheat yield after lupins with high nitrogen rates (118kg N/ha) reduces costs overall by 30 per cent.”

It was a similar story at Meckering, where the 60 per cent higher canola yield with high nitrogen rates (118kg N/ha) effectively reduced costs by 40 per cent.

Mr Easton said the experiments showed that productive legumes did not just potentially reduce the need for nitrogen fertiliser, they may also be what is needed to capitalise on investments in soil amelioration practices, improved genetics and better agronomic practices implemented to increase yield potential.

“The alternative of using more nitrogen fertiliser can be profitable but may not be enough to maximise returns in high-yielding environments where soil nitrogen reserves are low.”

These trials continued in 2024 to assess the legumes’ longer-term rotational benefits. Results will be available following harvest. With the Grower Group Alliance, GRDC is also working to close the economic yield gap for legumes.

Resources: James Easton’s paper, Can legume crops improve cropping returns in Western Australia?