Key points

- Gas-tight sealable silos should meet the Australian Standard AS2628-2010 for sealing but should only be sealed during a fumigation

- Open sealed silos after fumigation to protect seals and grain quality and, importantly, to prevent excess fumigant absorption

Outside fumigation, there is no need to seal a silo – in fact, sealing a silo for long periods increases the risk of grain degradation and silo damage.

There is a common misunderstanding that silos seal as a physical barrier to prevent insects getting into the grain. But silo seals and the Australian standard for sealing (AS2628-2010) are only designed to keep fumigant in the silo long enough to ensure successful fumigation with an adequate fumigant concentration for insect control.

So, what should be done with gas-tight sealable silos when they are not under fumigation?

When to seal?

A silo that meets the Australian Standard AS2628-2010 provides the buyers of gas-tight sealable silos with confidence they will get what they are paying for.

These silos will pass a five-minute, half-life pressure test when new. The half-life pressure test is a reliable method to ensure the silo will hold fumigant at an adequate concentration for the time required to control all life stages of stored grain insect pests – egg, larvae, pupae and adult.

Where a silo has been on-farm for some time, passing a three-minute, half-life pressure test should still provide adequate fumigant retention for insect control.

When ordering gas-tight sealable silos, ask the manufacturer to guarantee and include reference to AS2628 on the invoice, and insist a pressure test be demonstrated on delivery or construction.

The importance of the seal

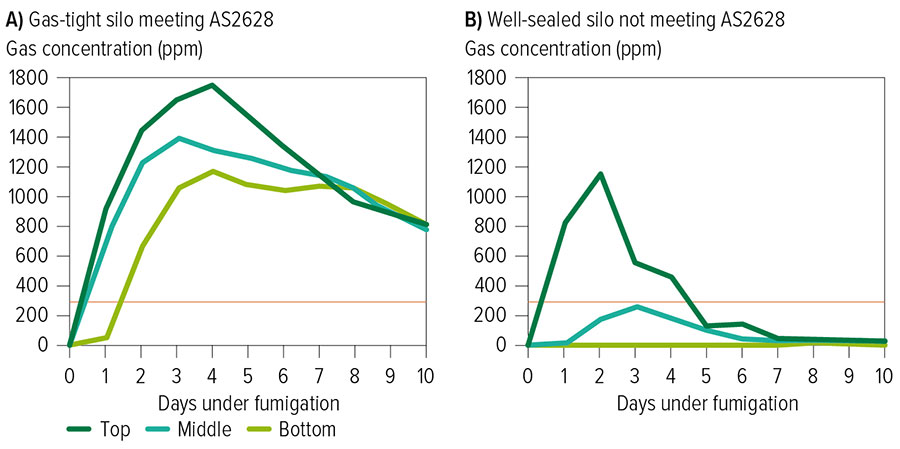

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries research, undertaken with GRDC investment, examined the variation in fumigation performance of two seemingly identical silos. Silo A passed a three-minute, AS2628 half-life pressure test. Silo B had slightly compromised seals, and could be pressurised, but was unable to meet the three-minute half-life pressure level to pass the test.

Silo A maintained more than 300 parts per million (ppm) of phosphine in all areas of the silo for seven days, as required to provide effective control of all insect life stages, including eggs and pupae (Figure 1A).

Silo B failed to maintain 300ppm for seven days and was unable to reach 300ppm in the middle or bottom of the silo (Figure 1B). Many insects would have survived the fumigation in silo B but, more alarmingly, fumigations in silos like this add to the growing issue of pests becoming resistant to fumigation gases.

Figure 1: Silo A, which met fumigation performance standards, maintained more than 300 parts per million (ppm) of phosphine in all areas of the silo during a seven-day test, as required to provide effective control of all insect life stages, including eggs and pupae. Silo B had slightly compromised seals and was unable to pass performance tests, maintain 300ppm for seven days or reach 300ppm in the middle or bottom of the silo.

Source: Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

When to open?

There are three primary risks with sealing silos for extended periods of time: grain degradation, structural damage and excess fumigant absorption.

When not fumigating, leave silos unsealed to allow free air movement. Air in the headspace, for example, can be very warm and carry considerable moisture. Allowing this to escape lowers the temperature of the grain in the headspace and minimises spoilage of the top layer of grain.

Structural damage or deterioration of seals can occur if the weather changes suddenly and the air inside the silo expands or contracts rapidly.

The pressure relief valve is fitted to gas-tight sealable silos to minimise the impact of rapid temperature changes by letting some air in or out if the differential pressure is too great during a fumigation. By design, the valve provides this safety measure without compromising the concentration of fumigant when the silo is sealed for fumigation.

But during rapid temperature changes, the volume of air to exchange can be more than the pressure relief valve can handle, putting the pressure seals at risk of damage. The most obvious way to avoid this is to leave the silo unsealed when not fumigating.

This issue is exacerbated when partially filled silos are sealed, leaving a greater volume of air in the silo to expand or contract.

There are three primary risks with sealing silos for extended periods of time: grain degradation, structural damage and excess fumigant absorption.

If partially filled silos need to be sealed for fumigation, the weather forecast should be monitored for rapid changes, including a cool front or a storm on a hot day.

Protect silo seals by ensuring the pressure relief valve and any piping to the headspace is of adequate size for the silo. For large (more than 750 tonnes) flat-bottom silos, two or more pressure relief valves are typically required.

Long-term sealing risks

Contrary to any past advice, growers should not leave silos sealed after fumigation. This practice is off-label and can lead to grain absorbing high levels of phosphine.

The label requirements for venting and withholding provide adequate time for any absorbed phosphine to be desorbed. But if grain is fumigated for more than the fumigation period prescribed by the label, additional phosphine can be absorbed, which will require a longer time for desorption.

This can create issues at delivery points where highly sensitive detection equipment is increasingly being used to identify the presence of phosphine gas.

If silos are sealed soon after filling, warm and potentially moist grain can produce condensation in the headspace, which will drip down the walls onto the grain, causing mould and grain spoilage.

Leave silos open to vent and breathe, without letting rain in, to avoid this issue. Use a vent that can be sealed for fumigation or, alternatively, lock the lid in a partially open position to vent while keeping the weather out.

Ideally, cool grain with aeration fans to create uniform moisture and temperature conditions to help prevent mould and insects.

More information: Ben White, 1800 WEEVIL, info@storedgrain.com.au